‘Broken Images’ turns the mirror back on all of us

Mauj Collective’s sharp take on Girish Karnad’s play captures the all-too-familiar chaos of living between languages

You don’t need to be a theatre person to understand Broken Images. You just need to have grown up here — thinking in Urdu, writing in English, and never fully trusting either.

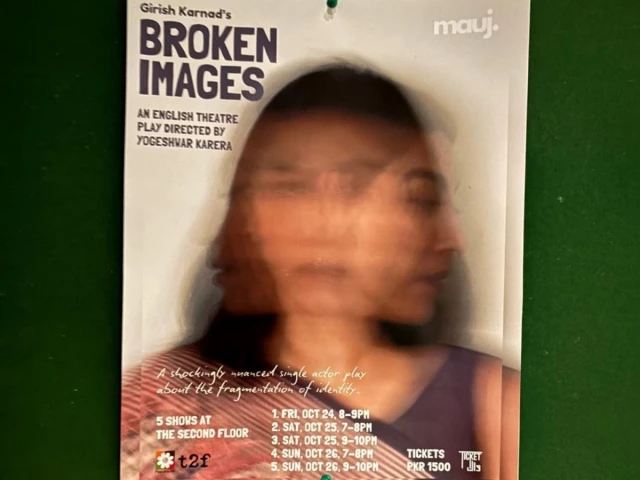

Directed by Yogeshwar Karera and staged by the Mauj Collective at T2F, the play is adapted from Girish Karnad’s play originally written in Kannada. Raana Kazmi plays Mahjabeen Raza, an Urdu short-story writer who becomes famous for her English-language novel The River Has No Memories. The story explores success, guilt, and how easily someone can lose control of their own story — especially when they’re the one who wrote it.

It begins with Mahjabeen giving a TV interview through her AirPods. She’s calm, charming, and a little smug — exactly how you would imagine a local writer on international television to be. She recalls how she was asked, “Do you see yourself as an Urdu or an English writer?” and she smiled and replies, “If I had known the people I would offend by writing in English…” The audience laughs, but it’s a laugh lined with discomfort. Everyone understands what it feels like to speak the “wrong” language in the wrong room.

Before the show, Karera told me this was what drew him to the play. “Karnad always used mythology,” he said. “But here he used technology. That felt modern, but also very grounded.” And he’s right. In Broken Images, gods are replaced by gadgets, and judgment doesn’t come from heaven anymore — it comes from a screen.

That’s why the set is simple: a desk, a chair, and a glowing monitor. Mahjabeen speaks to the audience with the confidence of someone who’s practiced every answer. When she says, “I’m not rich, just well-to-do,” the audience smiles at each other sheepishly. It’s the most Karachi thing to say: proud, but just enough to sound humble.

Then the screen turns on her. Literally. Suddenly, she starts talking back to herself — repeating her words, asking questions she can’t answer, catching every lie she’s told herself. And that’s when the mask begins to slip.

Kazmi plays Mahjabeen as a woman falling apart in real time. Her voice trembles, her smile stiffens, and her sentences begin to spiral. The breakdown is as loud as it is deeply uncomfortable. It holds your hand at first, then suddenly leaves you entirely on your own. When she screams, the audience freezes. When she laughs, they do too — not at her, but with her, painfully aware of the effort it takes to stay composed even as everything inside her is breaking down.

Through her sister Mehreen, the play shows how deep the language divide runs. Mehreen, who wrote in English despite being physically disabled, becomes Mahjabeen’s mirror and rival. Urdu represents her roots; English, her escape. Their conflict isn’t just about writing — it’s about who gets to be heard, and in what language.

“Isn’t this all our colonial hangovers?” Karera said. “English still feels aspirational for many people. But now, in some circles, it’s actually considered bad not to speak Urdu. This contradiction is at the heart of the play.” This is Mahjabeen’s story. But it is all of ours, too. English gives us credibility in the world but makes us suspicious at home. Urdu gives us authenticity but also confines us. We’re torn between two worlds that both want to claim us.

Technology becomes both judge and jury. The screen doesn’t tell her anything new — it only repeats what she already knows and forces her to face it. Watching her argue with her reflection feels like playing back an old voice note and wincing at how much of yourself you hear.

The direction is tight and deliberate. Karera builds tension through silences, pauses, and glances that last a second too long. By the time the screen starts talking, you already sense that something in Mahjabeen has been waiting to crack.

When I asked Karera what he hoped audiences would take away, he said, “That we carry so many contradictions without realizing how much they shape us.”

And he’s right. Broken Images is not really about a bitter woman as it is about all of us, talking in our broken mother tongues, translating in borrowed ones, trying to be both without ever being whole.

The play ran at T2F on Friday from 8:00–9:00PM and Saturday until Sunday from 7:00–8:00 PM and 9:00–10:00 PM.

COMMENTS (1)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ