Supreme Court allows Judge to work again, puts IHC order on hold

Experts say SC may refer matter back to IHC or hear quo warranto petition itself

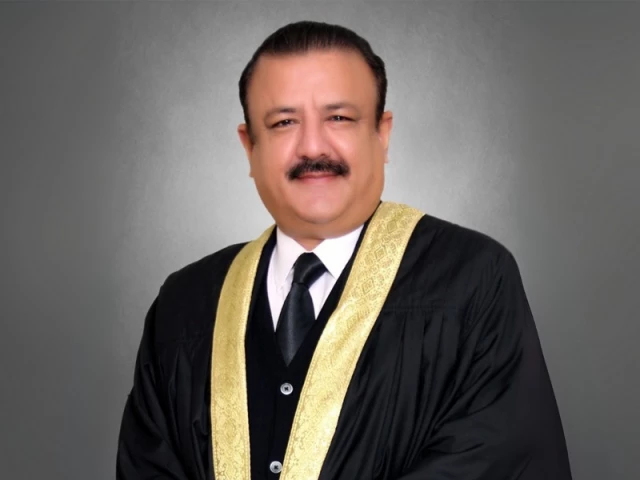

The Supreme Court on Monday suspended a Islamabad High Court (IHC) order that had barred IHC judge Tariq Mehmood Jahangiri from performing judicial work. The IHC subsequently issued a new cause list, restoring Jahangiri to single and division benches.

A division bench led by IHC Chief Justice Sardar Muhammad Sarfraz Dogar on September 16 had stopped Justice Jahangiri from performing his duties as it began proceedings on a quo warranto petition accusing him of holding a dubious LLB degree.

On September 19, five IHC judges, including Justice Jahangiri, went to the Supreme Court in person to file separate constitutional petitions, making eleven different prayers, including one seeking the quashing of the IHC order barring Jahangiri from judicial work.

However, on September 25, the University of Karachi cancelled the judge's LLB degree in light of a previous decision of its syndicate, further complicating the situation.

On Monday, a constitutional bench (CB) of the SCheaded by Justice Aminuddin Khan and comprising Justice Jamal Khan Mandokhail, Justice Muhammad Ali Mazhar, Justice Hasan Azhar Rizvi, and Justice Shahid Bilal Hassansuspended the IHC order.

However, despite securing interim relief from the Supreme Court, Justice Jahangiri may still face a bumpy road until the controversy surrounding his law degree is resolved.

The CB is likely to decide today (Tuesday) whether a high court can restrain one of its judges from judicial work through a judicial order. There is little chance that the CB will endorse the IHC order restraining Justice Jahangiri from performing judicial functions.

However, the stance of the Attorney General for Pakistan (AGP) will be crucial in this matter. The CB usually accords significant weight to the AGP's opinion, particularly after the passage of the 26th Constitutional Amendment.

Senior lawyers expect different possible outcomes from the bench.

After setting aside the interim order, the CB may refer back the matter to the IHC for first deciding maintainability of the quo warranto petition filed against Justice Jahangiri.

The CB may also hold that the complaint against the IHC judge is already pending before the Supreme Judicial Council (SJC), which is scheduled to convene on October 18.

IT can alternatively be advised to decide the writ of quo warranto against the IHC judge itself. In that case, all litigation records pending in the IHC and the Sindh High Court may be summoned for final adjudication by the apex court.

Some senior lawyers believe that the presence of five IHC judgesMohsin Akhtar Kayani, Babar Sattar, Tariq Mahmood Jahangiri, Sardar Ejaz Ishaq Khan, and Saman Rafat Imtiazin the courtroom during this case is very alarming for the judiciary. Now, all eyes are on the Supreme Court to see how it protects the independence of the judiciary.

Barrister Mustafa Nawaz Khokhar remarked that Monday's hearing was not about Justice Jahangiri but about the Supreme Court's role in safeguarding judicial independence.

"The appropriate forum to proceed against a judge of a superior court has been, and always will be, the SJC. The unprecedented process adopted by Justice Dogar amounts to usurping the SJC's powers and opens the door for future purges. Authoritarianism requires complete submission, and history will not look kindly upon those who choose to collaborate," Khokhar added.

Hafiz Ahsaan Ahmad Khokhar Advocate praised the CB's interim order, calling it expected and necessary, as restraining a sitting judge from judicial functions had no constitutional or legal basis.

"The suspension order reflects the Supreme Court's role in safeguarding judicial independence and sends a clear signal that such measures cannot be sustained in law."

Khokhar emphasized that the only competent forum to examine a superior court judge's conduct or continuation in office is the SJC under Article 209, not a division bench or full bench of the same court. This principle ensures that judicial accountability remains within its proper constitutional framework.

He said while administrative control may regulate the distribution of cases, restraining a judge from all judicial work is not an administrative act but a constitutional intervention, which falls exclusively within the jurisdiction of the SJC.

The Division Bench of the IHC, despite its best intentions, therefore acted beyond its lawful authority. The Supreme Court's suspension of that order restores the proper balance between constitutional forums.

Khokhar further noted that by issuing notices alongside the suspension order, the Supreme Court has set a much-needed precedent: judges of the same court should not, in the future, pass injunctive or restraining orders against one another.

This, he stressed, is vital for the institutional stature, credibility, and discipline of the judiciary. Such matters must be resolved either administratively or through the constitutionally mandated mechanism of the SJC, not through intra-court restraining measures.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ