Indonesia's silver men surviving on the streets

Economy forces Jakartans down difficult road

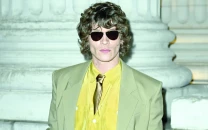

On a rainy day in Indonesia's capital Jakarta, three men coated in metallic paint known as the "manusia silver", or silvermen, brave the elements at an intersection near a mall to ask drivers for change.

It is an arresting act that comes with health risks, one some young Indonesians feel is necessary to make ends meet as the cost of living worsens and jobs dwindle after the COVID-19 pandemic.

"I'm ashamed to earn money like this. I want to find a real, more dignified job," said Ari Munandar, 25. "But the embarrassment disappears when you remember that your daughter and your wife are at home."

Barefoot, dressed only in shorts and daubed head to toe by the irritating paint, Ari, his brother Keris and their friend Riyan Ahmad Fazriyansah each take a lane in the road.

When the cars come to a stop they strike robotic poses in front of the drivers. The poses have little meaning other than to attract cash. On a good day they can pocket up to 200,000 rupiah ($12), but typically earn around 120,000.

That's much less than Jakarta's monthly minimum wage of five million rupiah and barely enough to cover daily expenses.

Every penny counts in a country where prices have risen steadily in recent years. A kilogram (two pounds) of rice, the archipelago's main staple, jumped by 27 per cent between 2015 and 2025, according to statistics agency data.

Meanwhile, according to government data, the number of people living below the poverty line in metropolitan Jakarta — a megalopolis of 11 million people - was up from 362,000 in 2019 to 449,000 as of September 2024.

"Many young people with few qualifications between the ages of 20 and 40 have found themselves unemployed," said Bhima Yudistira, executive director of the Centre of Economic and Law Studies.

After five hours at the intersection, the group returns home by hitchhiking a ride from a tuk-tuk.

Far from the capital's high-rises, children play near the tracks to the rhythm of the trains as Ari makes his way back to remove the silver. Squatting in front of a well and buckets filled with water, he splashes his body before scrubbing fiercely, his one-year-old daughter Arisya watching.

"At first the paint burned and I had a blister on my neck, but now it only stings my eyes," he said.

Once dry, he heads home to play with Arisya.

"As soon as I'm here I forget all the fatigue and the hardship," he says, smiling. "But I hope she never does what I do." afp

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ