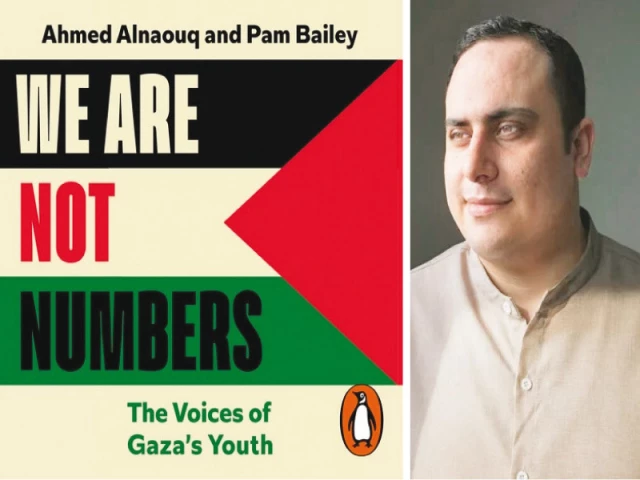

We are not numbers'

Palestinian writer collates stories of human loss in new book

When Gaza-born, London-based journalist Ahmed Alnaouq lost a staggering 21 members of his family to Israeli air strikes in 2023, he was left with the hallmark survivor's guilt question:"Why am I alive?" Now, speaking to Guardian, Alnaouq thinks he knows the answer: it is so that he can share the raw, human stories of Palestinian grief and resilience with the rest of the world.

Adamant that he would get the stories of the people behind the faceless numbers reported in the news, Alnaouq teamed up with American activist Pam Bailey in 2015 to create an online platform titled We Are Not Numbers (WANN) as a way for Palestianians who had lost loved ones to violence to channel their pain. The end result? A decade's worth of 74 moving stories by budding Palestinian writers, all brought together in a book titled We Are Not Numbers: The Voices of Gaza's Youth, to be released on April 24. Each chapter covers a different year, with events that have been covered in the news media given a harrowing personal perspective.

"We're chronicling history in Gaza, not by facts and statistics and news stories, but by the lived experiences of the people," Alnaouq told the publication. "It's not a political project; it's a human project."

Wanting to die

Alnaouq's work with his fellow Palestinian writers stems from a place of personal loss. Even before the violence that claimed members of his family in 2023, the journalist had an acute sense of the grief felt by his fellow Palestinians survivors. His first experience with the aftermath of violence came in the summer of 2014 when he lost his brother and four friends to an Israeli air strike.

"I wanted to die," recalled Alnaouq as he recounted his tailspin into depression. "I really, genuinely was waiting for the moment that I die so I can join my brother and just get rid of this life."

It was only when he reconnected online with Bailey, whom he had met in Gaza several years earlier, that Alnaouq was able to channel his grief. At Bailey's insistence, Alnaouq wrote a story about his brother in English, despite struggling with the language at the time.

"At first, I said no," stated Alnaouq. "My English wasn't very good."

However, after three months and several edits following a back-and-forth with Bailey, Alnaouq's story was published online, proving to be a watershed moment for the Palestinian writer.

"For the first time, I received messages of sympathy and support from people outside Gaza," he said. Having had little idea of how deeply his words would resonate with a wider audience, Alnaouq continued, "In my mind, I thought that all westerners don't like the Palestinians. They don't want to read our stories. But that proved me wrong. It boosted my confidence and made me feel I was wrong when I said there is no hope in this life."

Writing to survive

That was the turning point that led Alnaouq to realise that the steps he had taken could also help others in his shoes, leading directly to the birth of WANN. In 2015, 20 Palestinian writers – many of whom were English literature students – used the online platform as a means of therapy to write about the very human consequences of Israeli violence. Their words evinced feelings of not just dread, loss, despair, and poverty, but also painted a picture of the innate beauty, culture and architecture of Gaza, proving that it was more than a "dusty, horrible place" on the news.

"We were amazed by how talented young writers in Gaza were," said Alnaouq. "Every six months, we would recruit another 20 or 30. We would train them to write and help with their English. Over the past 10 years, we've published more than 1,500 stories and poems."

The writers Alnaouq has collaborated with include award-winning poet Mosab Abu Toha and the Al Jazeera journalist Hind Khoudary. Their combined efforts highlight the need for survivors to communicate their pain with the rest of the world when all else appears lost.

"We publish maybe three times more stories than before," said Alnaouq, reflecting on the journey his WANN platform has taken from its inception to the present day.

Against all odds

Those Alnaouq works with do not just battle a language barrier to get their stories shared; they also face the very real and seemingly insurmountable obstacles of having nothing to write on, and no way of sharing their words with anyone if they do.

"Most of our writers lost their homes," illustrated the journalist. "They lost their laptops. They don't have electricity or internet connection. But they write their stories on their phones, wait a few days for [an] internet connection and then submit them to us. Every month we publish 35 to 40 stories."

Through We Are Not Numbers: The Voices of Gaza's Youth, Alnaouq and his fellow survivors prove that where there is a will, there definitely is a way. The haunting words of dedicated Palestinian writers who pursue their goal in the face of catastrophic loss remain a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the stubborn refusal of hope to die.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ