Generating ‘AI art’ doesn’t make you an artist

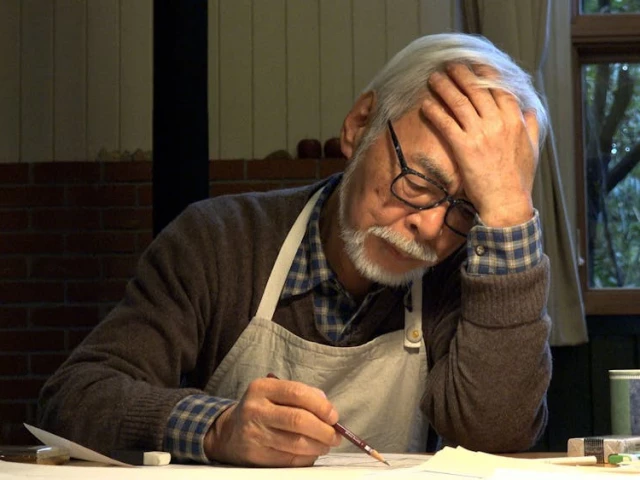

The recent AI Ghibli trend raises questions about copyright, ownership and labels

In the last few centuries, human life has significantly changed. From the industrial revolution to the information age and now the age of artificial intelligence, every era has faced new problems and ways to adapt to them. Today, we face a new challenge in the form of what’s called AI art.

The use of AI in art has received a lot of criticism. And while a number of arguments can be made in favour of the use of AI in art, it poses multiple dilemmas and raises moral and ethical questions.

Natural evolution

One may see it like this: the invention of cameras threatened the medium of painting, film wasn’t taken seriously as an art form early in the 20th century either, digital video has almost wiped out celluloid and streaming has affected the existence of cinemas worldwide. So AI art is the next step in this natural evolution of the combined art, engineering and technology.

However, a myriad of issues surround AI art. One of them, which answers the aforementioned evolutionary progression, is theft. Cameras, film or digital, didn’t generate work based on existing human art. One had to put in the time and skill to learn the equipment and know how to use it.

Whatever the medium, one must practice the craft and master it to produce original work. However, AI generates ‘art’ based on the data fed to it. That data is the existing work of artists used without their consent.

It raises two major issues: consent of artists who work is used to train the AI, and the fact that typing prompts is now an equivalent of putting in the hard work into learning all skills.

This doesn’t democratise art, it devalues it. If anyone can call themselves an artist by generating AI images or videos, then no one is. There is nothing to look up to and improve. It replaces learning a craft and paves the way for ready-made art not unlike that of Andy Warhol’s pop art. But even he put in more effort than typing prompts in an AI software.

AI art generation, thus, becomes an act of translation rather than creation. If you can type words, you can generate anything.

One must also take into consideration the current limitations of AI. While AI has merits in many fields, we must see what it has done to language. Anyone can read a paragraph and evaluate that it was written by AI. The sentence structure, vocabulary and grammar all follow certain patterns. And generally, AI-written texts are too bland in their language to the point that it doesn’t make you feel anything.

Meaningless mimicry

AI art is the same in that it’s devoid of any emotion. That emotion comes from the artist. It comes from the emotional journey the artist had, the catharsis that one feels upon putting in the effort in the act of creation. That’s all lost, leaving AI art a meaningless mimicry of human essence, prompted by lazy, untalented pseudo-artists who can’t be bothered to make an effort and learn a craft.

As the professor and Distinguished Chair of Information, Science and Technology at the University of Nebraska Omaha Dr. Deepak Khazanchi said in an interview with Hayden Ernst in the research paper titled Artificial: A Study on the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Art, AI can “mimic emotion maybe, but it cannot be emotional. It can mimic creativity, but it cannot be creative.”

Dr. Khazanchi, who has decades of experience in AI and machine learning, vehemently denies that AI can replace humans.

Another argument against it is the social and cultural context of art. Art is a uniquely human product and is fundamental to our existence. An artist creates after being exposed to internal and external stimuli which collide and offer us a connection with the world we live in. Art is how we justify our human existence and an act of creation is the process of affirming our place in this world.

We must also look at art as a way to connect to our surroundings and fellow humans. AI art generations rob us of the collaborative element of art-making, since we lose the process of creation itself, almost directly arriving at the end product. It results in the so-called art having no nuance or depth that arises from the human experience.

In the study titled Humans versus AI: whether and why we prefer human-created compared to AI-created artwork published by Lucas Bellaiche, Rohin Shahi, Martin Harry Turpin, Anya Ragnhildstveit, Shawn Sprockett, Nathaniel Barr, Alexander Christensen & Paul Seli in the Cognitive Research Journal in 2023, the authors state, “It may be that peoples’ preferences for art increase as their beliefs about the amount of effort that went into creating a piece of art increase.”

Limited scope

It also leads to a certain homogenisation of art. One may argue that it’s already happening in human art too, at least in the mainstream. However, if all art is made using AI, it limits the scope of art where everything is a copy of a copy of a copy with no room for change. It becomes a closed loop, a self-replicating simulacra of human experience.

But perhaps the biggest argument against AI art isn’t even related to AI art itself. It’s about the claim of the AI art generator as an artist. Ernst, in his paper, concludes that “it isn’t that the art isn’t good or creative. It can be very good. However, sometimes the process is more art than the final product. The images that the AI can currently produce are mimics of what can be made by people. While there may be a place for this type of art, it isn’t suited for display in an exhibit.”

The paper also aligns with what the study published in the Cognitive Research Journal. It found that people preferred human-created art over AI-created art. “This preference was particularly evident for criteria that communicated deeper meanings of the art (e.g., Profundity, Worth). On more-sensory levels, the difference between human- and AI-labelled art was much more modest, though significant differences were nonetheless observed,” it stated. “In conclusion, people tend to perceive art as reflecting a human-specific experience, though creator labels seem to mediate the ability to derive deeper evaluations from art. Thus, creative products like art may be achieved — according to human raters — by non-human AI models, but only to a limited extent that still protects a valued anthropocentrism.”

Hence, the issue isn’t merely the existence of AI-generated art, but rather the claims of generators as artists (or filmmakers). Similar to what Ernst says, such generations may have a place but it’s not in exhibitions or film festivals. And so using AI to generate your Ghibli avatars doesn’t make you Ghibli. And generating AI films doesn’t make anyone a filmmaker, just like paying for an NFT of an ape wearing glasses doesn’t make it your property (the Bored Ape NFT currently has more than 5000 owners).

I’d conclude by reiterating the fact that art is fundamental to human experience and existence. If generating automated copies of art makes you an artist, playing WWE 2k25 would make me a wrestler. Also, lip-syncing to songs on TikTok does not make anyone a singer.

The label of an artist comes from the agonising and ecstatic process of creation, informed by emotion and experience. If no human or cultural experience is behind it, art is rendered meaningless.

Have something to add to the story? Share it in the comments below.

1733130350-0/Untitled-design-(76)1733130350-0-208x130.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ