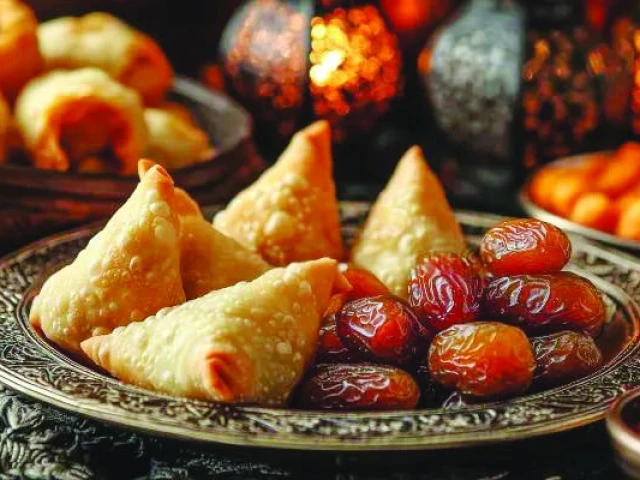

Beyond dates and samosas

Navigating Ramazan away from Pakistan comes with challenges

"Not even coffee?"

These are the awed words of an agnostic Caucasian teacher in New Jersey who first learns from me what fasting from dawn to dusk entails.

Thus with this imagery having sparked a fresh wave of longing in caffeine hounds, it is time to take a step back and reflect on the Ramazan experience in a non Muslim country. As the moon wanes away steadily towards the launching pad to Eid, does it really make any difference whether you observe this month outside Pakistan?

A different world

You get no prizes for guessing that the answer is "yes". For a start, it would occur to no one in Pakistan (or, for that matter, the Middle East or the Gulf), to query, "Not even coffee?"

Local supermarkets may have a larger stock of dates than usual, but that is where local culture and Muslim culture part ways. Whether you are fasting or not, office hours continue to run as regimentally as they do throughout the rest of the year. If you have been resourceful enough to land a working-from-home position, you can block your diary with something that sounds vaguely vital and escape the rigmarole of Teams meeting, which have rendered your throat hoarse and done no favours at all to your thumping caffeine withdrawal headache. Having cleverly blocked your diary, you can escape for a well-timed secret thirty-minute nap.

Fasting school children, on the other hand, enjoy no such luxury. Far from being able to pencil in secret naps, they are expected to remain alert and engaged throughout the mind-numbing tedium of geography lessons, regardless of how late they may have had to revise for impending GCSEs after coming back from the mosque the night before.

Things are equally grim in PE, where they have to somehow continue to jog at a steady pace alongside their non-fasting peers.

"We had to run, like, a bunch of laps, and then the teacher went, 'If you are not fasting, go and have a drink, and if you are fasting, I guess you just have to stay here and not have a drink'," says Anaya, a thirteen-year-old student.

Because she attends a diverse school with a robust balance of Muslim and non-Muslim cohorts, Anaya has no qualms about fasting during the school day, despite being amongst peers who have lunch during break or water after running laps. Far from being put off by fed and watered classmates, Anaya maintains she wants to keep up with her Muslim friends, despite her parents suggesting she take it easy on PE days.

"I don't want to be the only one of us not fasting, you know?" she says.

School and work may continue without the truncated working hours on offer in Pakistan, but when you draw the lens a little closer to home, things remain eerily similar – especially for the women who have imported extended family (or rather, extended in-laws) alongside themselves.

Kitchen duties galore

The moment that sun disappears from the sky the floodgates open for the woman tasked with all things food – especially if she lives with a caffeine hound, even if she herself cares little for either tea or coffee.

This is something that transcends borders, hemispheres, and possibly all celestial objects. Wherever you find yourself within the confines of our solar system, few Pakistani men will be foolish enough to allocate the drudgery of the kitchen to themselves when they have a woman nearby to do it for them. Even if Elon Musk finds a Muslim couple willing to relocate to Mars, it will still be the man sitting waiting to be served his usual quota of tea from the woman who is probably wondering why she didn't let him go alone.

For women who work from home, either in their capacity as one who is gainfully employed or as a homemaker, there is an air of liberation throughout Ramazan – especially when they share their quarters with a man who doesn't leave the house.

"I won't lie, it's amazing not having to make sure my husband has his lunch and tea on time," says Fatima, who lives in Windsor and works from home alongside her husband. "It is so nice to not be interrupted from whatever I am doing to get up and get his food ready."

Because Fatima lives with just her husband, however, she admits to relishing the freedom from the expectation of producing a steady stream of traditional fried items every evening.

"We just have regular dinner," she says. "I haven't made a proper iftar ever since we moved to the UK from Karachi. If I still lived with my in-laws, it would be different."

Burdened and resentful

Not every desi woman enjoys Fatima's sanguine fortune.

"My mother-in-law wants fresh rice for sehri every morning," confides Iman, who daren't give her real name lest she be outed for talking to The Express Tribune. Iman's mother-in-law moved to the UK from Bangladesh some thirty years ago, but did not leave behind her love for rice.

"If it was just me and my husband, it would be fine," continues Iman. "We'd just have a bowl of porridge and be done with it. My mother-in-law, however, wants last night's salan with fresh rice. It is so tedious."

Iman's battle cry is taken up by Nadia, who not only lives with her in-laws but also lives within easy reach of all of her husband's siblings.

"It is just one iftar party after another every night, and it is exhausting," says Nadia, who moved to London from Karachi after getting married in 2010. "At least in Karachi, we know someone else will come and clear up tomorrow morning!"

Here in the UK, halal shops embrace Ramazan with full fervour and stock up on every type of date imaginable, as well as filling their deep freezers with large packets of frozen samosas and spring rolls. Shops also stock frozen strips for the woman who prefers needless labour. And yes, there are women who spend their days deftly packing spring rolls even though a near identical ready-made doppelganger exists. Nadia is amongst them, albeit not by choice.

"The rest of the family prefers homemade samosas," she says with an air of resignation.

Nadia may be a deft samosa-maker, but she does not conceal her resentment at the expectation of doing it all without help. Nor is she thrilled at the looming prospect of Eid.

"We have an open house on Eid, and it is exhausting cooking for so many people. I never, ever enjoy Eid," she adds.

The situation Nadia finds herself in is a sad reminder that wherever a Pakistani woman finds herself amongst extended family, her joy at festive occasions – be it Ramazan or Eid – is sucked away by the expectation of non-stop cooking and solo cleaning. The Nadias of this world do not deserve this fate – although with Eid around the corner, they will soon be able to mask their resentment with their usual coffee come morning, noon or night.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ