Journalist killings reach record high in 2024

Six countries, including Pakistan and India, remain persistently dangerous for media workers

A surge in global conflicts and political crackdowns has made 2024 the deadliest year for journalists in over three decades, new figures from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reveal. At least 124 media workers lost their lives across 18 countries last year, a sharp increase that reflects the growing threats to press freedom worldwide.

Nearly 70 per cent of those deaths were linked to Israel’s military campaign in Gaza, where 85 journalists were killed, including 82 Palestinians. The data, compiled by the New York-based press freedom watchdog, points to a broader deterioration in journalist safety, as political unrest and armed conflicts escalate in multiple regions.

Sudan and Pakistan tied for the second-highest number of journalist killings in 2024, with six each. Sudan’s deaths stemmed from the country’s devastating civil war, which has left thousands dead and millions displaced. Pakistan, which had recorded no journalist fatalities since 2021, saw a spike in killings amid political unrest and increasing media censorship.

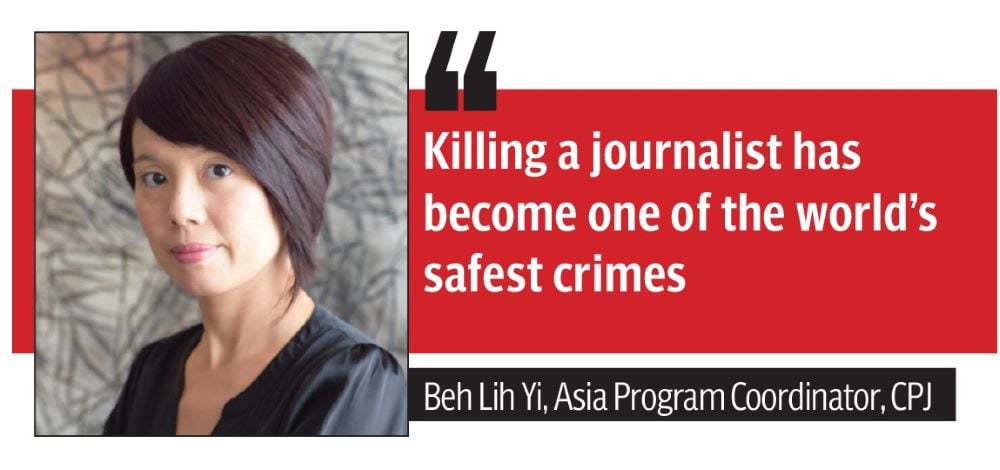

“It’s very clear from our latest report that today is the most dangerous time to be a journalist. The number of journalist deaths in 2024 marks the deadliest year on record since CPJ began tracking fatalities in 1992,” Beh Lih Yi, CPJ’s Asia Program Coordinator, told the Express Tribune.

Over the last twelve months, she explained, the media watchdog had documented the highest number of work-related killings, with freelancers accounting for close to a third of all cases. She noted that this troubling trend reveals the global nature of the crisis and the need for swift intervention.

Beh emphasized that government officials and local authorities have a duty to investigate journalist killings and ensure justice is served. “What we want to stress is that they are responsible for these investigations,” she said. However, she noted that there is often little willingness to hold those responsible to account, which creates a chilling effect on the media.

Consistently dangerous

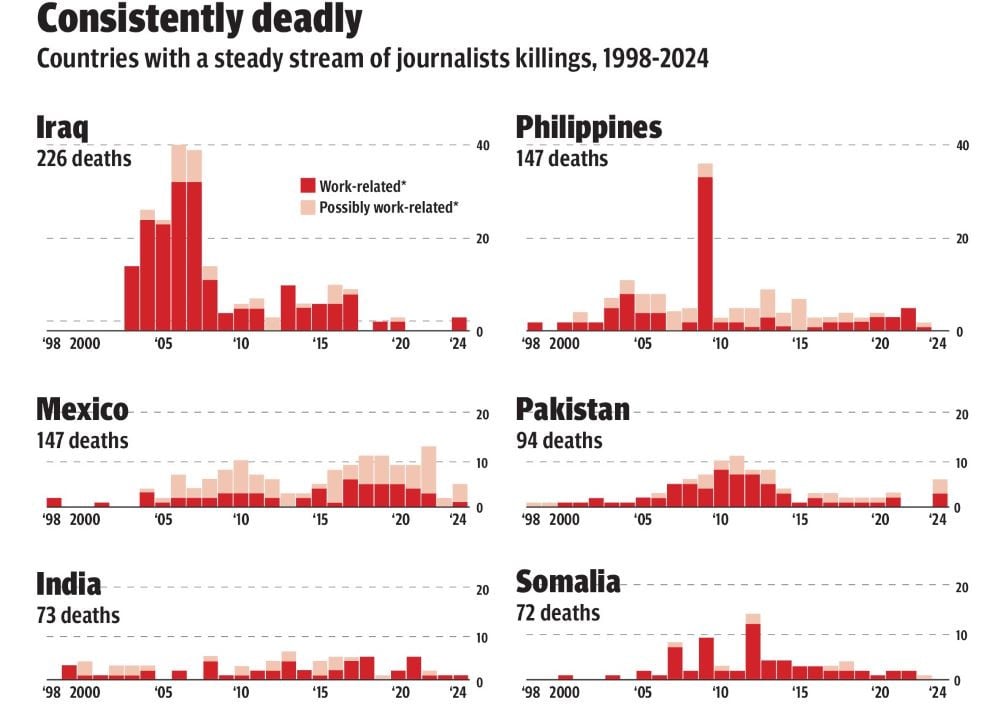

Beyond the dangerous spike last year, CPJ data reveals another troubling pattern – six countries—including Pakistan and India, which calls itself the world’s largest democracy—have remained consistently dangerous for journalists since 2000. Alongside Mexico, Iraq, Syria, and the Philippines, these nations have repeatedly recorded journalist deaths, with little to no accountability for those responsible.

Describing the killing of journalists as “one of the world’s safest crimes—a crime to silence the truth,” CJP’s Asia Program Coordinator stressed that the lack of accountability allows these attacks to continue, urging governments, including those in Mexico, India, and Pakistan, to take decisive action to prosecute those responsible and put an end to journalist killings.

According to the media advocacy group, in Pakistan, three of the six journalists killed in 2024 were murdered. Two others were killed after covering militant activity. India, which has long faced criticism for its treatment of the press, recorded the killing of at least one journalist last year, while continued threats and attacks against media workers have fueled an atmosphere of fear.

Referring to the recently passed Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act, which critics say is an attempt to stifle the press, Beh voiced concern over its implications for journalists. “Just last month, Pakistan passed a bill criminalizing false news,” she said, warning that the measure grants the government sweeping authority over the press. “We are very concerned about such legislation because it gives governments broad powers to silence journalists.” Under the law, she noted, individuals convicted of intentionally spreading false information that could incite public fear or unrest may face up to three years in prison, fines of up to two million rupees, or both. “Using ‘fake news’ laws to criminalize journalists threatens press freedom and the public’s right to information,” Beh cautioned. “At the same time, news organizations have a responsibility to ensure the safety of journalists. Every time a journalist is killed, we lose a truth-teller,” she added.

Elsewhere, Mexico remained one of the world’s deadliest places for journalists, with five reporters killed in 2024. The press freedom watchdog has consistently flagged the Mexican government’s failure to protect journalists, despite having mechanisms in place that are supposed to provide security.

When asked about the methods used to silence journalists, Beh said it was a combination of various tactics. Censorship, CJP’s Asia Program Coordinator noted, remains a key tool, with governments using legal and regulatory measures—sometimes unrelated to journalism—to target reporters. “Increasingly, we see financial and regulatory charges used to create a chilling effect on newsrooms,” she added.

Beyond legal measures, Beh pointed out that officials often use hostile rhetoric to erode public trust in journalists, which in turn increases the risk of violence. “When authorities fail to properly investigate journalist killings, it signals that such crimes are tolerated,” she said. “Killing a journalist is the ultimate form of censorship,” she cautioned, stressing that these tactics together create a highly repressive media environment.

Deadliest region

According to the New York-based press freedom group, North Africa and the Middle East accounted for more than 78 per cent of all journalist killings in 2024, with Gaza, Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq among the most dangerous places to report. In Lebanon, three journalists were killed in an Israeli airstrike, while at least 10 Palestinian journalists were murdered in targeted attacks, CPJ found. Iraq and Syria, both long-standing danger zones for journalists, saw deadly attacks resume in 2024. In Syria, four journalists were killed following the December 8 ousting of president Bashar al-Assad, raising concerns about the future of press freedoms in the country.

Beyond the Middle East, journalist killings were documented in Myanmar, Mozambique, and Sudan, where ongoing civil unrest has made reporting an increasingly lethal profession. The report also notes that in some cases, journalist killings are not isolated incidents but part of a broader effort to silence dissent and restrict press freedoms.

Rising contempt for press

President Donald Trump’s return to the White House earlier this year has posed a significant challenge to press freedom. The president frequently berates journalists and accuses news organizations—particularly CNN—of spreading false information.

Asked whether Trump’s hostility toward independent reporting could have broader consequences, Beh Lih Yi, the Asia Program Coordinator for the Committee to Protect Journalists, warned that such rhetoric undermines journalist safety and weakens press protections worldwide.

“These attacks on journalists’ credibility and their reporting contribute to an unsafe environment,” Beh said. “When such rhetoric is used in established democracies, it can send a message to less mature democracies that this kind of behavior is acceptable. This, in turn, emboldens regimes to adopt similar tactics to silence the press,” she warned.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ