Women of the Bach family

Little was known about the strong women of composer’s family until now

Anna Magdalena Wilcke (1701-1760) was a well-known soprano who in 1721 married the legendary classical composer, Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750). However, Anna Magdalena went down in music history not as a musician — but as Bach’s wife. That could be about to change.

It was not until the 1970s that music researchers in Europe began to focus more on women from the era who composed or played music themselves. “Women who were associated with men, such as Anna Magdalena Bach, were the first to come into focus,” said Kerstin Wiese, director of the Bach Museum, which is part of the Bach Archive Leipzig.

Giving women a voice

Maria Hübner, a musicologist and former Bach Archive employee, included the life stories of 33 Bach women as part of an exhibition at the Bach Museum, Voices of Women from the Bach Family. Wiese wants to highlight the Bach women as independent personalities. “After all, women are still overshadowed by men in musical life today,” said the museum director.

The names Anna Carolina Philippina Bach, Maria Salome Bach, Cecilia Bach and Catharina Dorothea Bach are hardly known. Yet these important women in the life of the Bach musical family not only supported their composing husbands and fathers by managing the family. They also wrote scores in beautiful handwriting, managed the music trade and published their husbands’ works posthumously.

Last but not least, some of them were professional singers themselves. Cecilia Grassi, for example, was a well-known Italian soprano who performed at the Venice Opera among other venues. As a prima donna at the legendary King’s Theatre in London, she met her future husband Johann Christian Bach, the youngest son of Johann Sebastian. After his death, the Bach widow ensured that one of her husband’s operas was performed as he had instructed in the score.

How women fell into musical oblivion

It was not until the 1970s that music researchers in Europe began to focus more on women who composed and played music themselves. “Women who were associated with men, such as Anna Magdalena Bach, were the first to come into focus,” said Kerstin Wiese, director of the Bach Museum, which is part of the Bach Archive and Research Institute in Leipzig.

Some of these women appear in reference works from the 18th century. “In Gottfried Walther’s 1732 music lexicon, you can find a whole series of female composers, musicians and also works that they composed,” explained Kerstin Wiese.

In the 19th century, however, these women disappeared from the music literature of the time. The Belgian author August Gathy even denies Johann Sebastian Bach’s daughters any musicality in his Musical Conversations Lexicon of 1835, intended as an Encyclopaedia for the Entire Science of Music for Artists. Only Bach’s sons are mentioned as talented descendants. “Gathy probably didn’t bother with the daughters at all, but simply had a preconceived bias,” said Wiese.

The difficulty of sourcing in Bach research

There are hardly any sources on the life of Johann Sebastian Bach, let alone on the women in his family. Every new discovery or insight into the Baroque composer is celebrated by Bach fans. Only one personal handwritten letter by Bach has survived, in which he also talks about the family with whom he could perform his own concerts — a feature of the Bachs’ annual extended family reunions.

In this letter to a school friend, Bach also explicitly mentions his wife Anna Magdalena and his eldest daughter Catharina Dorothea. He writes that his wife even sings “a clean soprano,” and mentions that his “eldest daughter doesn’t hit badly either” — which was quite positive for those times.

In an amusing song that Bach wrote for one of these family gatherings, we learn that the horse farmer poked and teased his sister Maria Salome with a fork. “We know Johann Sebastian Bach’s brothers, but hardly anyone knows Maria Salome,” said Kerstin Wiese from the Bach Archive Leipzig. “I just want it to be known that there was also a sister.”

The Koopman Collection

Anna Carolina Philippina Bach was a granddaughter of Johann Sebastian Bach. She worked for her father, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-1788), who was arguably more famous than his father Johann Sebastian in the 18th century, the age of classical music. Anna Carolina Philippina organized the correspondence and was in contact with music publishers, musicians and copyists. After her father’s death, she continued his music distribution business.

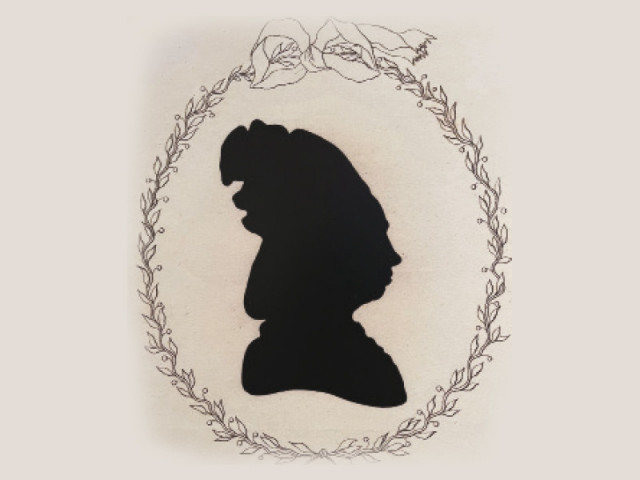

A silhouette from 1776 shows her portrait. It is one of the few existing portraits of the women of the Bach family. Further pictures of other women musicians shown in the exhibition come from the graphic art collection of Ton Koopman. The Dutch conductor and organist is President of the Bach Archive in Leipzig and a passionate collector of music. He has provided 25 portraits of women from his extensive collection of prints for the exhibition.

“I bought everything that had to do with music and then researched it. I was amazed myself at how many interesting portraits of women there were, including those of women making music,” the 79-year-old told DW.

Anna Magdalena Bach

The example of Anna Magdalena Bach shows just how important some women musicians were in the 18th century. Although there is no direct evidence of her fame, entries in the salary books at court suggest that she was well known. Johann Sebastian Bach and Anna Magdalena met at the court of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Köthen, where Bach had been employed as court music director since 1717.

Anna Magdalena was given a permanent position as a singer there in 1721 and earned the third-highest salary in the court chapel after Bach. This alone shows how much her voice was appreciated. When Bach took up the post of Thomaskantor in Leipzig in 1723, he was not only responsible for the Thomanerchor, but also for all the music in Leipzig’s city churches.

Anna Magdalena Bach was not allowed to perform there, however, as solo singing by women was forbidden in the city’s churches. After Bach’s death, she ensured that his famous textbook The Art of Fugue was published posthumously.

Meanwhile, her name has made a lasting impression over the centuries thanks to the “Anna Magdalena Bach music booklet,” which includes compositions by Bach and other composers. The booklet remains a work of music literature that almost every piano student knows today.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ