Battle for heartland: North Punjab's political chessboard

With Pakistan's 12th elections looming on Feb 8, all eyes turn to political hotbed in the northern expanse of Punjab

With Pakistan's 12th general elections looming on February 8, all eyes turn to the political hotbed in the northern expanse of Punjab, stretching from Attock to Jhelum. This semi-plain region, known as Pothohar, has a rich history of shaping the nation's political destiny.

Pothohar's unique blend of limited reliance on agriculture and a high inclination towards military service has been instrumental in moulding its social fabric and priorities.

The strategic significance of Pothohar is not confined to its geographic location. Beyond the federal capital's proximity, the presence of military headquarters, defence installations, and weapons manufacturing centres in Tehsil Kahota and Taxila elevates Pothohar's importance, setting it apart from other regions.

Boasting 13 National Assembly and 26 provincial assembly constituencies, encompassing Attock, Fateh Jang, Chakwal, and Jhelum districts, Pothohar, along with the three National Assembly seats of Islamabad, stands poised to be the linchpin shaping Pakistan's political destiny.

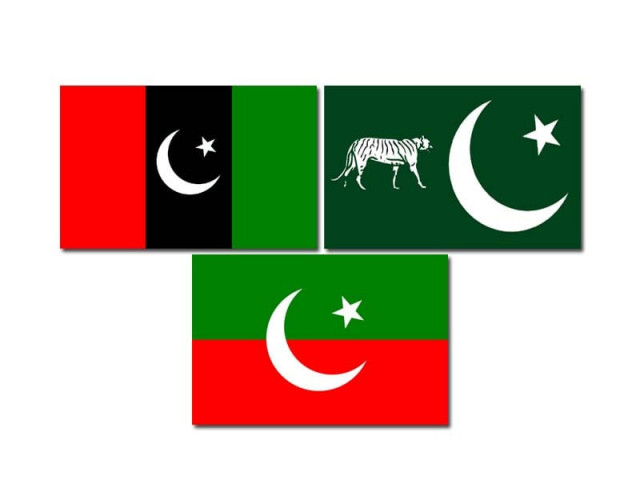

Examining the historical acceptance or rejection of popular parties in the last 11 elections unveils the intricate motivations influencing the upcoming election's outcome. Over the years, Pakistan's major political parties have taken turns securing national and provincial assemblies’ seats in this region.

In the 1970 general elections, the Pakistan People's Party clinched seven out of nine constituencies, while from 1988 to 2013, the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz dominated, with a brief exception in 2002. The winds of change in 2018 saw Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf succeeding in 11 constituencies of North Punjab.

As the 72 lakh voters prepare to cast their ballots, the selection of candidates by major political forces, their support from local factions and tribes, and their positions on national and regional issues will shape their choices.

Pothohar's distinctive demographic, characterized by a higher proportion of military service members passing down generations, plays a defining role in the region's economic, social, and political dynamics. General Syed Asim Munir, Pakistan's current army chief, and several other military leaders hail from this region, including Subedar Khudadad Khan, the first Indian soldier awarded the Victoria Cross in World War I, native to Chakwal district.

However, the impact of military dominance on the region's politics is a subject of scrutiny. According to Andrew R. Wilder, author of 'The Pakistani Voter: Electoral Politics and Voting Behavior in the Punjab,' the economy's reliance on jobs and business, rather than agriculture, influenced the political preferences of the rural voter. This translated into a fondness for Nawaz Sharif, as he was perceived to prioritize the interests of trade and commercial classes.

While democratic values are considered crucial in shaping Pothohar's political preferences, historical instances reveal a nuanced picture. Anti-establishment politics has deep roots in the region. The violent movement of students against Ayub Khan started at an educational institution in Rawalpindi.

Former Air Force Chief, Air Marshal Asghar Khan was defeated in the 1970 election by Khurshid Hasan Mir, a political worker from Rawalpindi.

General Zia-ul-Haq era Information Minister Raja Zafar-ul-Haq, who belonged to this area, lost the 1985 election. Similarly, Ejaz-ul-Haq was defeated in Rawalpindi in 1988 against Raja Shahid Zafar of PPP.

Can PPP regain its lost glory?

Pakistan People's Party Chairman Bilawal Bhutto Zardari had said in an interview that Punjab was the centre of his party and he will regain it.

Compared to the last two elections, this time PPP has organized and coordinated the campaign in Punjab. They are trying to attract old workers and leaders once again.

But the question is, why did the vote bank created by the PPP's electoral success in North Punjab in 1970 dissolve and is it possible to get it back now?

An analysis of the successes and failures of the PPP in the last 11 elections brings out some facts in the light of which the results of the PPP's strategy to regain its lost popularity can be understood.

Surprisingly, in 1993 and 2008, when this party formed the government in the federation, it managed to get only one and two seats respectively in North Punjab.

One of the reasons for this political decline is the new batch of politicians who succeeded in 1985. They have established themselves in their respective constituencies and with their influence based on their clan or groupings they have put a big dent in PPP’s vote bank. During the military regimes, local bodies were made powerful and were vested with resources and authority which brought forward a new leadership inherently ani-PPP.

PPP had boycotted the 1985 elections under General Ziaul Haq which cost the PPP direly.

Similarly, the PPP also does not have a strong party organization and many people capable of winning the elections left the party. The party could not bring up new leadership once an old ideologue died or left the party.

Malik Hakmain Khan was an important PPP leader and ideologue from Attock. After his death had a big void for the party in the region. Similarly, the party’s poorly organized new cadres would not replace PPP’s faces from Rawalpindi like Aga Riaz ul Islam, Sardar Saleem, and Qazi Sultan Mehmood.

Raja Pervez Ashraf speaker National Assembly has been winning elections on the party’s platform but his influence is limited to his area Gujar Khan. He has developed good ties in his constituency but we do not see any serious effort from his party to lead party re-organization in North Punjab.

PPP had a little ray of hope for the emergence of new party faces with the rise of Mustafa Nawaz Khokhar the son of former Deputy Speaker Haji Nawaz Khokhar. He was not only close to Bilawal Bhutto Zardari as his spokesperson but also very energetic in reorganizing the party in Punjab, particularly in Punjab.

After a long time, the PPP could muster a successful power show in Islamabad in 2017, thanks to Khokhar’s hard work. However, the PPP could not keep him along when he differed with the party’s decision to side with the powers that be on some important matters. Instead of tolerating his opinion, PPP top brass accepted his resignation as senator and as a member of the party. He is contesting upcoming elections as an independent candidate in the federal capital’s two constituencies and is expected to secure sizeable votes.

Former PPP secretary general of PPP Dr Ghulam Hussain from Jhelum has parted ways with the PPP. Farrukh Altaf, the son of former Punjab governor Chaudhry Altaf, who had contested the elections on the PPP's ticket in the past, is the candidate of PML-N in the current election.

Malik Amin Aslam, the son of the former leader of the People's Party, Malik Muhammad Aslam, who became a member of the National Assembly from Attock in 1988, left the People's Party and was elected as a member of the Assembly on the ticket of the Q-League in 2002. In the previous government of Imran Khan, he worked as an advisor.

Ghulam Sarwar Khan, who won the last two elections from Rawalpindi on a PTI ticket, also contested the 1990 and 1993 elections on behalf of the People's Party.

Sardar Mumtaz of Chakwal, who gave PPP the only seat from Rawalpindi Division in 1993, broke away from the party and was elected as a member National Assembly on a PML-N ticket from the same constituency in 2013.

Ghulam Murtaza Sati became MNA of PPP from Rawalpindi in 2002, but he also joined Tehreek-e-Insaaf in the last election.

Analysts believe the political failures of the People's Party are due to the party's own mistakes as well as the planning of powerful quarters.

Pakistan People's Party still has a vote bank of 10,000 to 20,000 in the constituencies of this region but most electables have left the party, especially after the tragic death of Benazir Bhutto.

Now Bilawal Bhutto is leading an aggressive political campaign to attract the anti-Nawaz Sharif vote once again.

How effective is the pro- and anti-Nawaz vote bank?

After Zia-ul-Haq's death, the next two elections 1988 and 1990 were fought between Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and Zia-ul-Haq's supporters. But after Nawaz Sharif gained popularity in 1993, the next elections were held on pro and anti-Nawaz Sharif factors.

Pro-Nawaz Sharif's political sentiments were fully expressed in the 1997 election when PML-N won all the seats in North Punjab. Similarly, in the 2013 election, Nawaz Sharif's personal popularity became the reason for his party's success in this region.

The absence of Nawaz Sharif from the election scene in the 2002 and 2018 elections strengthened the anti-Nawaz vote bank.

The PPP, in an effort to regain lost ground, strategically nominated General (retd) Tikka Khan a retired army chief for elections in 1988 from Rawalpindi and Shahid Nawaz, brother of late former Chief of Army Staff General Asif Nawaz, in 1993. In a curious coincidence, the PML-N has fielded Bilal Azhar Kayani, son of the former Surgeon General of the Army Major General Retired Azhar Mehmood Kayani.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, analysts argue that it's not just military backgrounds but the prevailing political situation matters more in the voting preference in the region.

The pro-Imran vote bank

Professor Mujeeb Afzal of Quaid-e-Azam University suggests that the anti-Nawaz vote historically went to the People's Party, but with PTI's emergence in 2013, a significant portion shifted allegiance. The PTI's victory in 2018, he argues, was a result of uniting the anti-Nawaz vote bank of the PPP with Imran Khan's new, young voters.

The 2024 elections introduce a new factor—the pro-Imran vote bank. With Imran Khan facing legal challenges, questions arise about the effectiveness of this vote bank and the impact of PTI's organisational challenges and defections on the election results.

Imran Khan, who was convicted in the Toshakhana case, has now been sentenced to long sentences spanning up to 14 years of imprisonment in three more cases.

A large part of PTI's vote bank is in place, but its real challenge is organisational disintegration and defections of elected representatives and party leaders from the party.

If this situation is compared with the political situation faced by PML-N and PPP in the past, PTI also seems to be suffering from the same crisis that these two parties have gone through in the past.

Seven former MNAs who won from Rawalpindi division on PTI ticket in 2018 are not contesting the elections from this party this time. Three of its former MNAs have joined other parties.

Only one candidate who participated in the last election is again in the fray from PTI in the National Assembly constituencies. New faces have been nominated for the National Assembly from the remaining 12 constituencies.

Fear, confusion and hopelessness are the biggest challenges for PTI workers after the May 9 incidents and PTI's loss of election symbol. Which will have an impact on the results of the upcoming elections.

As the political scenario unfolds, the constituencies of North Punjab located around the political and military centres of Pakistan, are anticipated to play an important role in the formation of the next government. The convergence of democratic values, historical factors, and evolving political dynamics promises an engaging and closely contested electoral battle in the heart of the power centre.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ