Ali Hassan's 'Tanha' is an ode to contemporary Urdu poets

Artist discusses evolution, collaborations and the art of composing music

KARACHI:

Singer-composer and vocalist of the Karachi-based band Aam Tateel, Ali Hassan’s latest record and first solo project Tanha underpins the artist’s transformations over the years, particularly since his band’s last release Khudsar. “Solo” is a cautious qualifier for Tanha, which came out on November 15 and is in many ways a collaborative endeavour that sets out to reimagine the singer-record relationship. But what changed from Khudsar to Tanha?

“I think we were a lot more idealistic [then],” offered Ali, sitting down for a long and candid chat on the years preceding Tanha. “I was trying to say something explicitly social and political in nature with that album.” In its 13-track album, Khudsar debuted the band’s subversive intent to coalesce Urdu contemporary poetry and alternative rock as social commentary.

In contrast, Ali furnishes Tanha as a personal odyssey through loneliness as intricate and generative - a becoming of one’s self. “What has changed between then and now is that there are many things I’d like to do simply because of the act of doing them. There is music I want to make simply because one day I wake up with this longing for this kind of music that does not exist.”

The intimacy of Tanha is never a distraction nor does it forget its genesis. Remarking on his and his band’s proclivity to fuse Eastern Classical traditions with Western instrumentation, the singer observed how such experimentations are not always successful. “The ghazal has changed, therefore it’s now appropriate to explore, when mandated by the words, when allowed by the poetry itself,” he added.

The thought of a metal rendition of Aaj Jaane Ki Zid Na Karo elicited an immediate rejection from him. As per Ali, for all intents and purposes, khayal is a genre for private embodiment not outward expression.

Among the poets to lend their words to Khudsar, Jaun Elia remains a pronounced influence on Ali. The renowned poet re-appears on the singer’s latest record, but not without setting the stage for more contemporaries and new voices. “With Tanha, I worked with three living poets, and the next album will hopefully be only living poets.” Ali nodded at Jaun’s relative obscurity years ago when he began making music, commending the cultural efforts underway to appreciate the poet.

Jaun’s poetic deliberation on the existential facets of life in its broad and narrow parameters has often prompted his recognition as a melancholic artist. For Ali, many characterising the philosopher’s angst as depression are misguided, further inspiring him to compose Jaun. “Depression, as I understand it, is a lack of vitality … a lack of energy to engage with life. Sadness is not depression and I think that nuance was lost in the way that people looked at Jaun.”

In fact, Ali contended, Jaun was seldom “sad and broken” - one exhibit of which is his poem, Ai Subh, adapted into a slow melody on Tanha. “I think Ai Subh is one of the few Jaun’s ghazals where I felt him vulnerable. I thought its arrangement should be slow to parallel that,” he shared.

Alongside Jaun’s profound impact, the singer also attributes his record’s tone and composition to formally studying music in an academic setting. Expressing his intentions to specialise in ethnomusicology, Ali explained how his music production courses directed his attention to the nitty-gritty of composition.

He described, “I used my lessons to learn the different softwares, to learn different techniques for composition…explore ideas about texture, ideas about vertical structures, ideas about horizontal structure as well. Obviously, music theory, he classes. Gaining more and more knowledge of chordal movements, harmonic rhythm, underlying structure, underlying logic...”

Despite the rich socio-historical regard for compositional practices, among fans and audience, songs have long been relegated to the singer’s domain. Ali agreed and expressed his discontent with this limited reception, citing his study of different cultures and histories of music as helpful in tackling the “egocentrism” of singers.

This appreciation also extends to his ease at outsourcing lyricism - by borrowing words from poets. Like one cannot own a raag, music is a wider communal practice, rather than a lone undertaking. “I am firmly aware that there is a big universal current and I'm just one little speck in it. Very beautiful, but small,” he said.

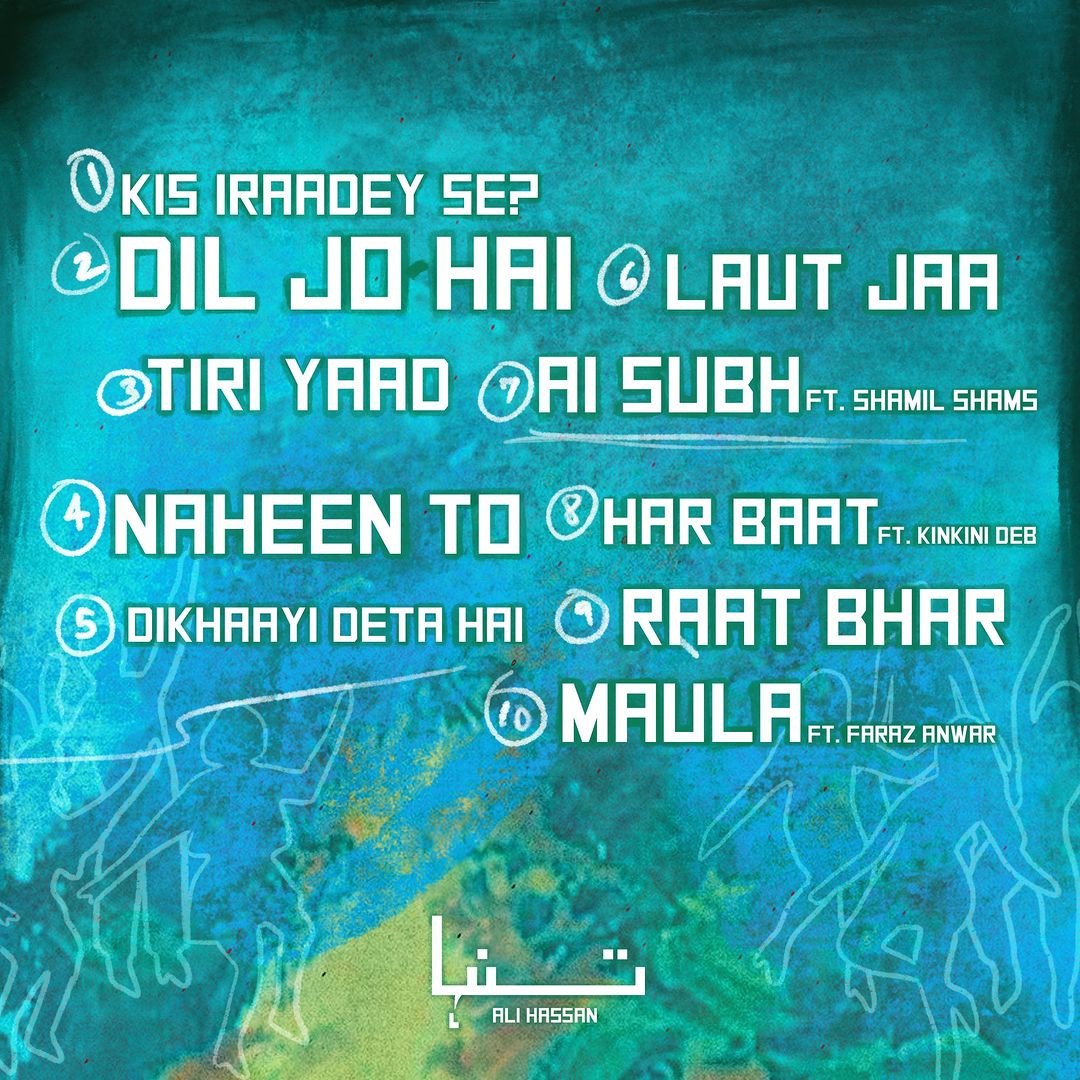

The collaborative aspect manifests most saliently in the asynchronous recording of Tanha. The 10-track-record features various multinational artists, representing eleven countries. Ali credits the “quarantine jams” where musicians would contribute their parts from different locations which would be combined in the mixing and production stages. Self-explanatory, the practice popularised remote recordings during the COVID-19 lockdown unlocking new possibilities.

Have something to add to the story? Share it in the comments below.

1719921789-0/dua-lipa-(1)1719921789-0-270x192.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ