Our society imposes a lot of restrictions on women. Even today, girls are told “You are a girl, you can’t do this!” or “What would the people say.” Under the garb of tradition, culture and honour, women’s movement, andeven education opportunities are restricted and their personal growth hampered. Some women, however, did not accept the status quo and chose to carve a niche for themselves, showing the way forward to others.

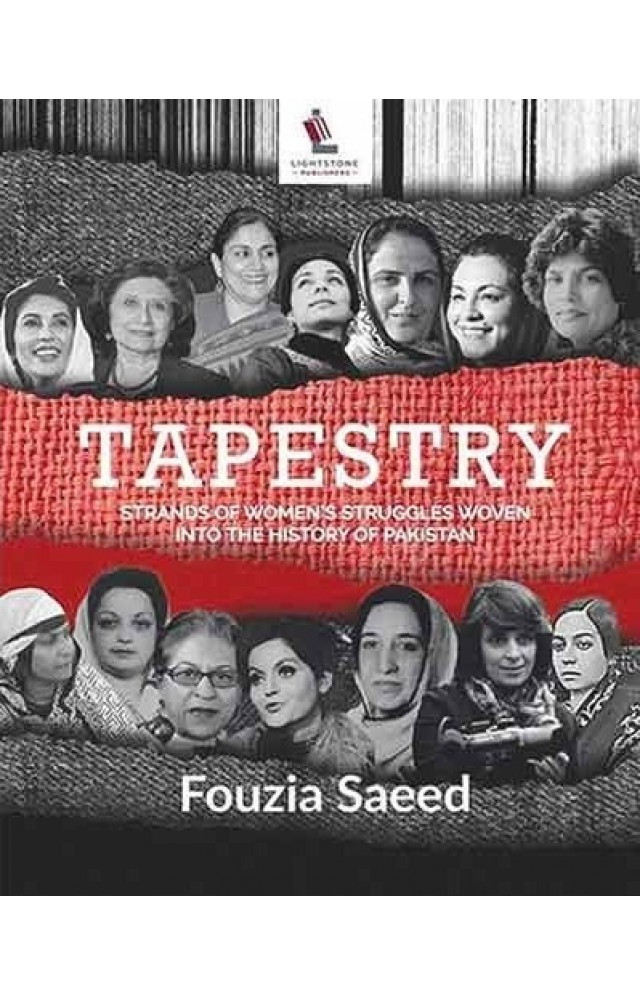

Tapestry: Strands of women’s struggles woven into the history of Pakistan, by Dr Fauzia Saeed — a social activist, gender expert, trainer, development manager, and author, who has written extensively on Pakistani culture and social issues — takes the readers on a journey through Pakistan’s political history. It traces the evolution of women’s struggles — from the Pakistan Movement till the present day — and explores how Pakistani women have been able to progress in the face of a changing and often oppressive socio-political environment.

Over the decades, Pakistani women have used many strategies to expand the space available to them. Saeed identifies seven dominant strategies, referred to as strands that women used to match the political environment, in different eras of our history. While each strand is related to a historical era, one strand slowly tapers off as the new one develops.

Along with discussing these strategies, profiles of individual women are given to show how they contributed to the collective struggle. These profiles complement the trends and deepen the readers’ understanding of women’s lives and the resistance they faced.

The book starts with the formation of the Muslim League and its struggle for an independent homeland. During the pre-Partition era — Political Awakening Strand (pre-1947) — despite observing purdah and living in seclusion, many Muslim women became politically aware and worked for the freedom movement, achieving important milestones.

Perhaps it is through their struggle that the Muslim League men realised that they cannot win without the support of their women. The British government too, approved several legislations supporting women’s rights, including Child Marriage Act 1929, the Dissolution of Muslim Marriage Act 1939, and the India Act of 1935, which also forms the basis for the voting rights for women. Also the practices of sati and female infanticide were outlawed.

Besides Fatima Jinnah and Rana Liaquat Ali Khan, there were many more who remain invisible. Noor-us Sabah Shah was born in a conservative family, but joined politics to contribute to Muslim League’s struggle for the creation of Pakistan. Mai Bakhtawar physically defied landlords from taking away the harvest, and is one of the inspirers of the Sindh Tenancy Act of 1952. Fatima Begum not only wrote about girls’ education, but also established a girls college on her property, to push education and political awareness among women.

After Independence, the focus of women’s efforts turned to social welfare to help women overcome the traumatic experience of Partition. Rather than question the system or the status quo, they set out to provide basic medical services, set up basic schools for children in camps, find missing family members, and support those who lost their family.

Prominent women of the Social Welfare Strand (1947–1950) era include Shaista Suharwardi Ikramullah, who created an Artisans’ and Craftsmen’s Committee to help organise the artisans and craftsmen, who in search of sustenance, were becoming common labourers. Begum Salma Tassaduq organised social welfare for the refugees and played an important role in resolving the issue of kidnapping of women during migration.

During the third strand — the Political Collaboration Strand (1950–1977) — women were increasingly seen in public life. They engaged with the government for their collective political and legal rights, often working with commissions appointed by the government.

An important achievement during this era was the passage of the historic Muslim Family Law Ordinance (1961), which curtailed the right of the husband to marry for the second time without the permission of the first wife.

Prominent women during this era include Begum Jahan Ara Shahnawaz, who was instrumental in pushing for basic rights for women to become a part of Pakistani law; Attiya Anayatullah, who struggled to make sure that the family planning programme continues; Fazlia Aliani, the first woman MPA from Balochistan who established Anjuman-e-Khawateen-e-Balochistan (Organisation of Women of Balochistan), and encouraged women to enter public life.

While the earlier years of Bhutto era were marked by many reforms, such as opening of senior posts in Foreign Service, and other elite services for women, under Ziaul Haq the political system became increasingly repressive towards women. Following the imposition of harsh policies and discriminatory laws, women became more confrontational, despite facing beatings, tear gas, jail time, and torture. Important methods used in this strand, i.e. Reactive confrontation (1977-1988), included protest rallies, civil disobedience, and street theatre.

Mehtab Rashdi refused to cover her head on TV as directed; Salima Hashmi, after cancellation of her TV show, along with others began to perform politically charged skits at WAF events, and at street corners. While Hamida, an active member of the Hari Tehreek, struggled for tillers’ rights, Rehana Sheikh worked on a bigger change in the system as member of the Sindhiani Tehreek.

The Women’s Action Forum (WAF) struggled against the Hudood Ordinances, and the proposed amendment of the Muslim Family Law Ordinance. Despite protests from various quarters, the bill of evidence went through the legislative procedure and became a law, as did the Qisas and Diyat Ordinances.

The Development Orientation Strand (1989–2000) saw women’s organisations concentrating on improving social sector outcomes. The influx of development aid from foreign donors financed the expansion of community groups; the many rural development programmes and other initiatives gave women a chance to improve their lives in terms of better health, education, and other services.

Since these donors focussed their attention on improving Pakistan’s poor social indicators, the local organisations also matched their priorities with those of the donor agencies.

During this strand the status quo was rarely challenged by the civil society, though later issues such as violence against women, power politics, participation in decision-making, and control over resources began to receive attention. Although the campaign against the Hudood Ordinances remained a permanent feature of the struggle, protests now focussed on specific discriminatory judgements or proposed laws.

Mariam Bibi, a Pashtun woman from a conservative family, struggled against both her family and society to study, and later founded an organisation Khawendo Kor (the house of sisters) that changed the lives of the women of similar background in her province. Shandana, daughter of a diplomat, joined the Sarhad Rural Support Programme, and helped women organise themselves, form organisations. Zarine Aziz, pioneer manager of the First Women’s Bank, played a major role in making the bank a viable entity and fought tooth and nail to prevent its privatisation through collective agency.

The Strategic Activism (2000–2016) dominated during the periods of Gen Musharraf, the PML-N, and the PPP. As civic groups began to find more space to operate, many more women’s movements started to take off, using a mix of strategies including advocacy, resource mobilisation, and lobbying to persuade, pressure, and collaborate with state institutions to achieve their demands. Women saw progressive men as their strong allies, though continued to struggle against chauvinistic men, ruling landed elite, oppressive parliamentary units, religious fundamentalists and bureaucratic managers. Women protested on the streets to get the government to the negotiating table.

Women who became agents of change include Nusrat Ara, who fought to get an education, and later ran in the local bodies elections which gave her an identity in the community. Akeela who as member of the peasant movement, started the Peasant Women’s Society to focus on women’s rights within their own community, as she felt that men do not help when it comes to women’s issues. Shad Begum, a resident of Lower Dir, refused to accept women’s exclusion from political activities, and her struggle, strategic thinking, and hard work changed the political landscape of her area. Mukhtara Mai is an example of both individual as well as collective agency. She proved that women who experience sexual violence have the choice of remaining a victim or fight back and impact the lives of others.

During the democratic era, a few movements can be cited as examples of strategic activism, such as the Lady Health Workers Movement, where women used a range of strategic tools, including street protests, to achieve their demand for job security, increased pay, and to be treated with dignity. They faced repeated police beatings, water hosing and tear-gassing but eventually achieved unimaginable success. Bushra Arain, founder and core leader of the Movement, and Nasreen Munawar, president of Punjab chapter of All Pakistan Lady Health Workers Association played important roles.

The Alliance Against Sexual Harassment (AASHA) movement started in 2001, focussed on helping working women to come together to restore their dignity at the workplace. The AASHA members worked with parliamentarians and succeeded in getting two laws against sexual harassment passed by the Assembly and the Senate in 2010. The passage of these two sexual harassment bills opened the path for more progressive legislation.

With social media gaining enormous popularity, social activists emerged. During the Virtual Activism Strand (2016 to date) technology not only changed the social and political landscape but how women’s movements operate. For example, during the Nurses’ Movement, Hifza Khan and her colleagues used their mobile phones to keep in touch with all the stakeholders to make sure that they are not tricked during their struggle for their rights.

While control on freedom of speech and mainstream media continues to increase, there are signs that some quarters want to control social media as well. In the past, street activists were beaten and thrown in jail, now blog writers and Facebook and Twitter users are being threatened.

On the women’s rights front, the use of social media has become the norm for pitching battles. Along with younger women, many of the older women’s organisations started to complement their work with social media tools. Activists began uploading films and messages on social causes.

Women from all classes in Pakistan entered unchartered territories and are pushing in different ways to reclaim more space. They are serving as Air Force jet pilots, police commandoes, as well as in other non-traditional professions. Others are making themselves more visible in the public space by riding two-wheelers as a way of reclaiming public spaces. Photographs of women riding motorbikes went viral, while tweets initiated a public discussion both for resistance and support.

A refreshing initiative is the Girls at Dhabas. Selfies of young women sitting at the street cafes, where usually men from lower-middle class have tea and snacks, have become viral. Some criticised that it was not proper behaviour for young girls, but others were happy to see young girls questioning why women cannot meet up with friends anywhere out of their private spaces.

While researchers and social activists would benefit from the enriching and informative discussions in the book, it should be a part of recommended reading for college and university students. It establishes that despite all odds against them, Pakistani women have achieved a tremendous lot and that uneducated people too can change paradigms as long as they have an awareness of their problems and the resolve to change things.

Rizwana Naqvi is a freelance journalist and tweets @naqviriz. She can be reached at naqvi2012rizwana@hotmail.co.uk; All information and facts are the responsibility of the writer.

1732243059-0/mac-miller-(2)1732243059-0-165x106.webp)

1672385156-0/Andrew-Tate-(1)1672385156-0-165x106.webp)

1732240377-0/mac-miller-(1)1732240377-0-165x106.webp)

1732240636-0/WhatsApp-Image-2024-11-21-at-19-54-13-(1)1732240636-0-270x192.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ