Pitfalls of import substitution

If Pakistan becomes more protectionist, it will make industry more uncompetitive

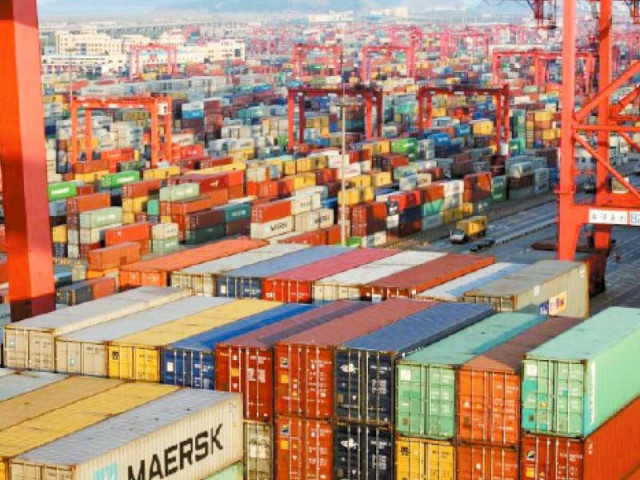

The National Security Committee (NSC) has recently decided, among other things, that import substitution should be the first step in strengthening the economy.

Since none of the NSC members is an economist, they will not have realised that import substitution policies always result in adding to an anti-export bias. Such policies have never worked in any country.

The current Finance Minister Ishaq Dar tried them during his previous tenure, but they hampered our exports. Trying the same prescription is most likely to have similar results.

The distinction is evident in comparing similarly placed countries where one followed import substitution, and the other moved on to export-led growth. One example is Argentina and Chile.

Raul Prebisch, Argentina’s influential economist, advocated import substitution policies, whilst “Chicago boys” economists have led Chile’s economic upward spiral on the back of exports since the 1970s. Now 50 years later, we can see the results.

Argentina, one of the wealthiest countries before embarking on the import substitution path, is now mired in deep economic problems. It has been to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) 22 times. In 2018, it borrowed $40 billion, and in 2022, another $44 billion to meet its obligations.

On the other hand, its neighbour Chile, which was once a relatively poor country and whose inflation had reached 600% in 1974, is now one of the most prosperous countries in Latin America.

Similarly, India and Pakistan have followed import substitution policies since independence, with India being a more protectionist economy. By the late 1980s, both countries started running into severe trade deficits and had to seek IMF’s assistance. In return, IMF insisted on opening up their economies.

While both countries started liberalising from 1990 onwards, India’s pace was more consistent. By 2008, India had been able to reduce import duties on non-agricultural items to 10% (with limited exceptions). With lower tariffs, it was able to diversify and better integrate its economy globally.

Since embarking on export-led growth in 1991, Indian exports of goods and services have risen from $23 billion to $660 billion.

On the other hand, Pakistan’s liberalisation process was always two steps forward and one step back. After a short period of rapid liberalisation from 1997 to 2002, Pakistan’s export of goods and services started growing by an average of about 15% annually. They doubled from $10 billion in 2001 to $20 billion in 2007.

However, when Pakistan started reversing its reforms from 2008 onwards through levies of additional and regulatory customs duties, its exports started stagnating.

During Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N)’s previous government, when import substitution policies were at their peak and customs duties were regularly increased – reflecting a tax share increase of almost 50% at the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) – Pakistan’s exports started falling sharply. In terms of GDP, they decreased from 12.24% in 2013 to 8.58% in 2018, the lowest level since 1972.

It is also possible to compare the performance of some specific industries across countries based on their import substitution policies.

The auto industry is one such example. In the 20th century, most developing countries followed import substitution or localisation programmes. However, after the advent of World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules, countries such as China, India, Turkey, Indonesia and Thailand abandoned import substitution policies.

In contrast, countries such as Argentina, Egypt, Pakistan and Russia continued with deletion or import substitution policies. Unlike the first group of countries, where autos and auto parts have become a major export item, the latter group only produces low-quality vehicles for domestic use.

If Pakistan becomes even more protectionist on the pretext of import substitution, it will make the local industry more non-competitive. Rent-seekers will benefit from it, and consumers will be further burdened.

The poorest section of society will be hit the hardest with indirect taxes having a far more adverse impact on them. Pakistan’s isolation from the global economy will grow further, and the trade deficit problem will become further acute. Hence such a decision needs a careful review.

The American-British economist Abba Lerner discovered in 1936 that domestic firms selling in a protected sector are artificially more profitable than those in export markets where a government imposes an import duty to protect it from foreign competition.

This protection creates an “anti-export bias,” as the tariffs, intended to reduce imports, end up reducing exports instead.

We have two models of economic development before us. South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam follow the export-led policies of Abba Lerner, while Argentina and Egypt follow Raul Prebisch’s import substitution policies.

Pakistan’s policies so far align with the latter group. We need to change course in the right direction.

The writer is currently working as a WTO trade arbitrator. Previously, he has served as Pakistan’s Ambassador to WTO and FAO’s representative to the UN at Geneva

Published in The Express Tribune, January 9th, 2023.

Like Business on Facebook, follow @TribuneBiz on Twitter to stay informed and join in the conversation.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ