Four relevant questions Pakistani dramas raised in 2021

In the midst of abusive marriages and problematic idols, some dramas owe praise for their substance

KARACHI:Television is undeniably the most popular medium in Pakistan. The target audience for small screens largely comprises lower to lower-middle-class households, especially housewives.

The ones who don’t have access to OTT platforms such as Netflix or Amazon Prime to watch ‘better’ content– this is what they see and construct their realities from. Instead of capitalising on that, the industry only cares for TRP.

I am not even someone who watches ARY content on the regular but in the past few months they have produced:

— Aimun (@bluemagicboxes) December 25, 2020

- Merey Paas Tum Ho

- Jalan

- Nand

- Jhooti

- Dunk (apparently a show about falsely accused men)

Fahad Mustafa has funded 4 of these projects.

It is not news that the Pakistani TV industry mostly produces content that internalises misogyny and encourages a regressive mindset. However, some drama serials stood out for finally addressing relevant issues. The producers and teams involved understood the responsibility well and used their platform to raise important and relevant questions pertaining to Pakistani society.

Is gender a social construct?

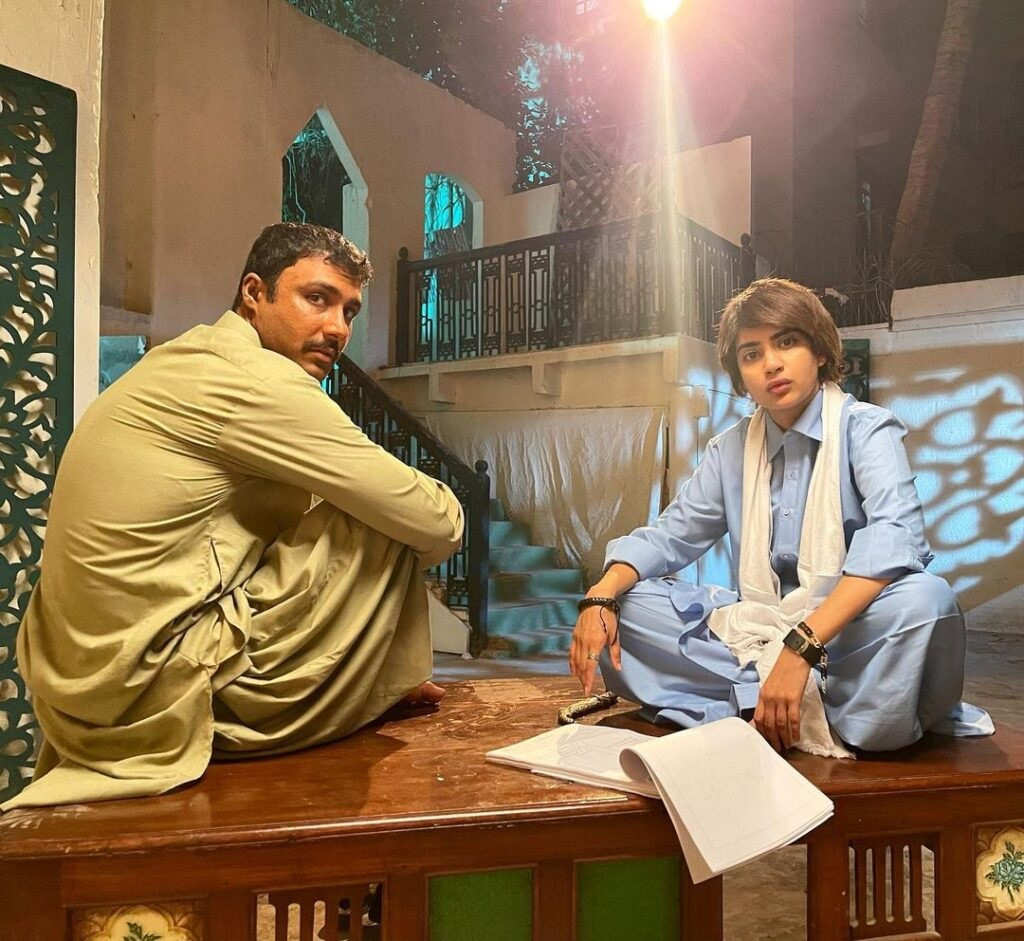

This one raised one too many eyebrows, as expected. Hashim Nadeem’s writing tackled the important issue of being queer and the hypocrisy that follows in the drama serial Parizaad. Currently airing on TV, Shahzad Kashmiri’s directed serial showed how once you break free from societal constructs and understand gender fluidity, even your blood doesn’t treat you like your own.

uff dilawar deserves a spinoff!!!! what an incredible, nuanced character and what an INCREDIBLE performance by saboor aly! #parizaad

— Zoya Rehman (@pind_wave) December 11, 2021

Society, including your family, wants you to conform to the rules around and if you don’t, it alienates you rather than accepting the natural process, disguising it as a sin to inculcate fear.

Dealing with the issue at hand with the utmost sensitivity, Parizaad illustrates how difficult it is to come out to oneself and others and the guilt that comes with it. Kudos to Saboor Aly essaying the character of Bubbly, later identified as Dilawar, eloping from his home following a confrontational scene where he explains the conundrum to his parents.

Naturally his parents, unable to digest it, try to categorise his behaviour as mere ‘confusion within’, where Aly’s Guru serves as the medium to connect the dots on how normal it is for him to not conform to a constructed gender.

With the LGBTQ+ movement getting more awareness, it was brave of Hashim to show a queer character as one amongst a set of family people can relate to, subtly normalising the concept for viewers.

Are widows allowed to live complete lives?

Taking a jibe at how child marriages cost children the opportunity to grow, Momina Duraid’s Dobara tackles societal stigma and other controversial issues from its first episode only. Hadiqa Kiani, who essays the role of Mehru, marries early to an older man who dies.

Being widowed at an early age, the show revolves around her navigating her way through taunts, societal expectations, and the patriarch's (her late husband) internalised voice to get the freedom and childhood she missed out on.

#dobara I wish they had shown Maahir actually fell in love with Mehro. A narrative that is much needed to be shown. I don’t know how the script will handle this ahead but for me Maahir marrying her out of no choice defeats the very point this drama is supposed to be about. pic.twitter.com/7f4rJQX6jr

— Rabia Mughni (@rabiamughni) December 22, 2021

Our society bars widowed women from having a life after the loss of their husbands. They’re seen as charity projects, undeserving of love and laughter, who are supposed to behave modestly and refrain from enjoying life ahead of them. However, Dobara shows a widow rediscovering herself, one step at a time, by redeeming lost opportunities and inner peace with symbolic acts of rebellion.

Is there such a thing as ‘marital rape’?

TRIGGER WARNING!

Of course, there is. Surrounding the conversation on consent even after you’re married, Qissa Meherbano Ka openly addresses how it shatters women while making them question the problem with it.

Qissa meherbano ka reminds me of Ranjha Ranjha Kardi Hai, stellar performances by all the actors including Mawra Hocane and Ahsan Khan, now they have touched the subject of marital rape and i want to see how they handle it now, the drama has taken a 180° turn#Qissameherbanoka pic.twitter.com/5VqLasX6yk

— Shayan Obaid Alexander (@ScouserSamar7) December 24, 2021

Getting criticism for its morbid portrayal and Meherbano (Mawra Hocane) enduring the trauma while living in the same house, it shows the reality of how change doesn’t come overnight.

In a country where victim-blaming is common and marital rape, isn’t even recognised, it will be unnatural to show a woman leaving the house when something so traumatic happens, and I’m glad they depicted the justifications society demands.

Let’s hope the show presents a resolution to the issue where she breaks free from her own inner critic and gets justice.

The inhumane face of society?

It’s 2021 and we should not need reminders through entertainment channels to justify how illegal and wrong child marriages and sex trafficking are.

FINALLY found a new Pakistani drama that has such an amazing storyline. A must watch. Featuring powerful performances from @Hadiqa_Kiani @SakinaSamo @bilalabbas_khan

— Kanwal Ahmed (@kanwalful) December 2, 2021

Touching on child marriage, finding love again & SO many other great topics. 😭❤️👏🏽#Dobara on @Humtvnetwork pic.twitter.com/0aqyMOD3d2

While Dobara brilliantly tackled the consequences showing how flashbacks of Naumaan Aijaz controlling and intimidating the child-wife Hadiqa into following his commands haunted her life decisions, Dil Na Umeed Toh Nahi sheds light on its causes by highlighting the family’s contribution to the criminal act without sugar-coating or theatrics.

The drama's called Dil Na Umeed Toh Nahi & was issued a notice by Pemra couple of weeks ago for "not presenting the true picture of Pakistan".

— Hassan Choudary (@hassanchoudary) March 11, 2021

Sadly it's neither getting views nor ratings. Why? Because the Pakistani audience has been fed nothing but garbage over all these years

It unveiled the inhumane face of society, putting the onus on families and authoritative figures, often wrongly set on pedestals, selling or abusing their children in the face of adversity.

Long way to go

The Pakistani TV industry has been stuck in a rut that plays around the trope of the run-of-the-mill scripts which essentially tell the audience to learn patience and resilience via adultery, child marriages, domestic violence.

why ary digital always make serials like jalan, hassad, nand, choti, jhooti whyyy

— s (@shehrezaat_) December 20, 2020

While this year did not bring a stark difference to our reel realities, the aforementioned drama serials stood out by thinking outside the box and addressing issues that are considered taboos in society. Although with its own set of issues, they were breathers amongst the claustrophobic cloud of misogynistic content. While it certainly is a step forward in the right direction, such scripts can be counted on fingers.

Dulhan. Jalan. Nand. Mohabbat Tujhe Alvida.

— Kanwal Ahmed (@kanwalful) October 23, 2020

Just the names of trending dramas in Pakistan these days. Names that also become the storyline of most dramas, when put together.

These serials managed to shatter some belief systems or at least start conversations on them, but the set structure of the media industry still controls the way society is represented, and will probably do so until the stakeholders decide to experiment with fearless narratives, questioning Pemra’s biased list of rights and wrongs.

Bee Gul, screenwriter and director, in an interview with The Express Tribune, once said that such “alternative voices should run parallel with the patriarchal voice of the television,” and we cannot agree more.

These dramas brought a much-needed alternative voice– even if it was in subtle hushed ways, but this is just the beginning, the representation can be more direct, with the right trigger warnings, to ensure viewers are ready for what’s to come.

Have something to add to the story? Share it in the comments below.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ