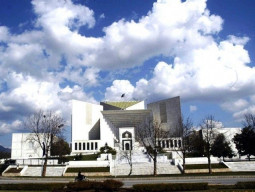

A debate on regulating the discretionary powers of the Chief Justice of Pakistan (CJP) has intensified after a Supreme Court larger bench’s order earlier this week.

Currently, the CJP enjoys unfettered discretionary powers to constitute benches, fix cases and initiate public interest proceedings. Likewise, being chairman of the Judicial Commission of Pakistan (JCP) and the Supreme Judicial Council, the CJP also has vast discretionary powers in the processes of the appointment of judges and their removal.

A five-judge larger bench, headed by acting Chief Justice Umar Ata Bandial on Thursday held that the chief justice was the “sole authority by and through whom the suo motu jurisdiction can be, and is to be, invoked/assumed” under Article 184 (3) of the Constitution.

Read Only CJP can take suo motu notice, rules SC

However, those judges who want to structure the CJP’s powers were not included in the larger bench, which was hearing a legal question, regarding invoking the suo motu jurisdiction.

Earlier, Justice Qazi Faiz Isa and Justice Yahya Afridi had called for regulating the CJP’s discretionary power to exercise suo motu jurisdiction as well as forming benches on constitutional matters.

Justice Isa – in a letter to Chief Justice Gulzar Ahmed on February 10 – noted that the Supreme Court often castigated the arbitrary exercise of discretion, yet unstructured discretion was exercised while making benches, hearing important constitutional matters.

“If the Executive’s transgressions are not checked, and instead benches are reconstituted and judges restrained, the people suffer. To exclude senior judges from the benches when important constitutional issues are to be heard neither serves the institution nor the people,” the judge said.

Justice Isa said that the Supreme Court was the final arbiter of all disputes and the custodian of the Constitution. It had been tasked with ensuring that the Executive did not overreach or act contrary to the Constitution.

Justice Isa said that the issue of unstructured discretionary powers had been left unattended by former chief justices and not taken up at full court meetings. He also sent a copy of the letter to Justice Maqbool Baqar, who is at number four on the seniority list of the Supreme Court judges.

In June 2020, Justice Afridi – while writing a dissenting note in Justice Isa case – observed that the apex court should be more careful, while exercising its advisory and suo motu jurisdictions because no appeal could be mounted against its judgments and opinions on those matters.

“To maintain judicial discipline and to uphold the rule of law, there is an inherent and dire need for judicial introspection; to structure the unfettered discretion of the worthy Chief Justice of the Supreme Court to constitute benches of the Supreme Court to hear and decide cases under Article 184 (3), and in particular suo motu actions, lest the exercise of such jurisdiction may be seen to have been abused.”

Justice Afridi, however, observed that passing any definite findings on this crucial matter in the current petition would not only be swaying from the issue at hand but also, on many counts, would be premature, as the matter was already subjudice before the Supreme Court.

The judge noted that the scope and extent of the term “matters of public importance”, as provided under Article 184 (3), had been an issue of perennial deliberation of the top court.

“The judicial consensus reached is for the same to encompass any issue affecting the legal rights or liabilities of the public or the community by large, and it is not restricted to an individual or a group of individuals, how so large the group might be.”

During the tenure of the former chief justices, Saqib Nisar and Asif Saeed Khosa, the apex court tried to structure the CJP’s powers on judicial as well as administrative side but nothing so far has been finalised. The first full-court meeting was held on February 6, 2019 to deliberate on the issue but no apex court official was present during the two-hour session.

According to the minutes of the meeting, it was resolved that “the issue of exercise of jurisdiction under Article 184 (3) of the Constitution was discussed threadbare from all possible angles and it was affirmed that such jurisdiction will be exercised in accordance with the Constitution”.

Senior lawyers were of the view that there was no consensus among the apex court judges to regulate the public interest jurisdiction and giving right of appeal in suo motu cases through amending the Supreme Court rules.

In December 2019, the then chief justice Asif Saeed Khosa had shared with other apex court judges a draft of the proposed amendments to the Supreme Court Rules, 1980 to regulate the suo motu power, exercised by the CJP to adjudicate public interest matters.

According to the draft, the chief justice will take suo motu notice on any matter after consulting with two senior-most judges. Later, the matter will be referred to a bench that will examine the matter on the judicial side. The bench’s decision could be challenged through an intra-court appeal (ICA), which will be heard by a larger bench. However, the fate of former CJ’s draft rules is not known.

On the other hand, Justice Umar Ata Bandial and Justice Munib Akhtar in their rulings observed that it was for the CJP – as the “master of the roster” – to determine the composition of a bench “and he may, for like reason, constitute a larger bench for hearing the review petition”. Similarly, now both judges have given judicial order in support of the CJPs discretionary power to exercise suo motu jurisdiction.

COMMENTS (2)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ