How has Pakistan's beloved auto sector fared since the 2016 policy

Put consumer welfare to the fore, and the love affair will continue

Very few will argue that Pakistan’s auto sector is the country’s most beloved and simultaneously hated industry. The love stems from an individual desire to own/upgrade one’s ride, while the hatred for it is rooted deep into decades of lack of choice, absence of safety features, expensive options, and what is perceived as outright exploitation of the Pakistani consumer.

A similar argument was made by the government in its Automotive Development Policy 2016-2021 where it stated – in a nutshell – that while important and crucial for economic growth, the aim should now be to attract investment and ensure consumer welfare. It took a jab at the Big Three, and criticised them for “having issues of safety and reliability features with surplus unutilised production capacities and lack of competition”. The government also recognised the demand-supply gap in certain segments, and pointed at the “unjustified delays in delivery”, eventually arriving at the obvious conclusion that investment should be promoted. It set out finalising a policy for which it received a little bit of criticism, more than a few threats, but mostly, positive reviews that the next phase of Pakistan’s auto sector would not only attract investment and more options, but also increase healthy competition.

Fast forward a few years, and Pakistan is witnessing the fruits of that endeavour.

While the growth in sales has not been achieved – the government targeted an ambitious production of 350,000 units by 2021 – new entrants have brought significant investment and choices. The tariff structure for completely knocked down (CKD) as well as completely built units (CBU) was reduced from 2017, and envisaged to continue till 2021. Despite pressure, threats, and criticism, the policy was rolled out and adhered to.

Through incentives offered under Greenfield and Brownfield investments – the former being installation of a plant to produce a “make” not being made in Pakistan, while the latter was aimed at reviving non-operational or closed operations on or before July 1, 2013 – Pakistan saw at least three new companies biting hard for a share of the market slice with several others trying to stay in the news with various announcements. The reason why these auto policy points have been mentioned – even though they do take the passion and interest away from reading an article about cars – is that there is a chapter on ‘consumer welfare’ where advance payment on purchase of vehicles is discussed. It states that the advance payment cannot be more than 50% of the price, and that the “price and delivery schedule, not exceeding two months, shall be firmed at the time of booking”. Any delay over two months would result in “discount @ KIBOR plus 2% prevailing on the date of final delivery/settlement from the final payment”. This was meant to reduce delivery lead time.

In simple terms, the government envisaged a delivery time of maximum two months. If there are delays, which are likely to happen in case a vehicle becomes hugely successful, one would imagine that orders are halted so that the lead time remains under two months. How much of this is being followed is anybody’s guess.

This brings us to the second point.

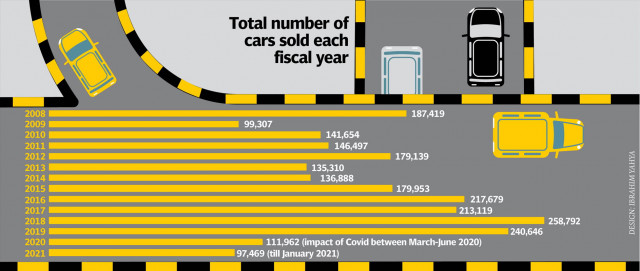

Pakistan’s auto sector production has seen a very bumpy ride. In fiscal year 2008, production of vehicles (passenger, jeeps, and pickups) stood at over 187,000 units. The very next year – due to implications of the global financial crisis – production went down massively to a little over 99,000 units. One could argue that this was a once-in-a-blue-moon event, and growth was likely to be sustainable now.

However, from even such a low benchmark, the industry only saw three more years of growth before production declined again from near 180,000 to 136,000 between 2012 and 2013. The cycle repeated. Another three years of growth, and production hit a peak. It was followed by another year of lower sales, followed by another increase before the industry faced its toughest test yet – massive rupee depreciation, high inflation, high interest rates, expensive cars, and if that was not enough Covid-19. The end-result: production hit 112,000 units, a level not seen since the financial crisis.

Here, one should take into account four months of slow activity due to Covid-19 that resulted in the 53.5% year-on-year sales decrease, but it was not like the industry was headed towards much growth that year anyway. Car sales are impacted by several reasons including access to financing, interest rates, prices, new variants, and most of all, a consumer’s willingness and ability to allocate a sizable amount of their income/profits to buying an asset/liability – depending on how you want to classify it – that will depreciate over time.

With a public transportation system that leaves much to be desired, the auto sector has a lot going for it – a stable policy by a government that did not cave in, and an ‘efficient dealer network’ that is able to, through the immediate ownership premium it charges on new vehicles, gauge how much of a price increase will be digestible. Critics can argue that the auto sector has its fair share of risks, but what business doesn’t. As long as you have a consistent policy, greater by-road travel, and an import duty structure in place that protects the local industry, you cannot really complain much.

With the auto policy set to expire this year, and the arrival of new vehicles likely drawing to a close as well, the government now needs to sit down, review, and chalk out a comprehensive plan for the next decade. Its already shown a part of its hand by mentioning electric vehicles, and is likely to be more environment-friendly than any previous government. As long as consumer welfare is put to the fore, Pakistan’s love for the auto sector will trump its hatred for it.

The writer is former business editor of The Express Tribune, and winner of the Citi Journalistic Excellence Award 2018. He holds a MBA from Cass Business School, and is currently associated with the CEJ-IBA. His Twitter handle is @bilala_memon

Published in The Express Tribune, March 1st, 2021.

Like Business on Facebook, follow @TribuneBiz on Twitter to stay informed and join in the conversation.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ