Ladakh stand-off — the big picture

At this point China has the choice to de-escalate which is what India is hoping for through its diplomatic efforts

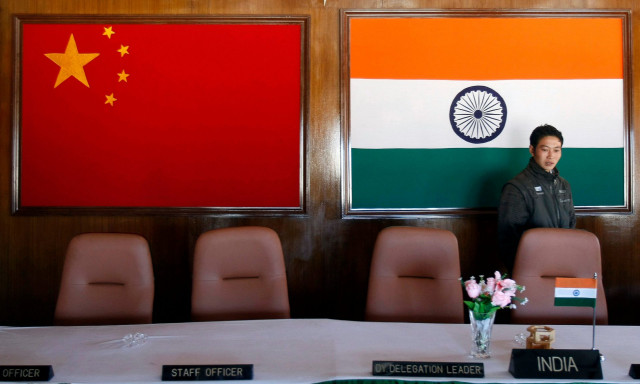

A Reuters file image.

Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO) is at the northern edge of Ladakh, less than 20 kilometres from the Karakoram Pass, that opens into the Chinese side. Between 2015 and 2019, the Indian side has added an ambitious network of roads to regions bordering China, including the 255km Darbuk-Shayok-Daulat Beg Oldie (DS-DBO) road in Ladakh. This road leads right to the last frontier at DBO and even further right up to the Karakoram Pass.

There have been standoffs between the two before, like in 2013, when the Chinese Army crossed the DBO by 30km with a platoon-sized contingent. On the same day it made an incursion on the Depsang Plain. India on the other hand had made structures in the disputed Chumar Sector — they retreated to status quo after negotiation, but the incidents made it clear that the dispute on demarcations is unresolved and alive.

In 2017, Chinese troops attempted to extend a road southward in Doklam, in an area it disputes with Bhutan. Doklam is a tri-junction point between Bhutan, Indian-Occupied Sikkim and China. The tri-junction is adjacent to the Siliguri Corridor, a 22km narrow stretch of land between Nepal and Bangladesh, which is India’s only entry point to the seven northeastern sister provinces. India fears that if China invades Siliguri, it will not only immediately seize the disputed Arunachal Pradesh but also mobilise dissent elements in the rest of the cut-off seven sisters that are already swarming with freedom movements. Just like India feels threatened, Indian buildup in Ladakh right up to the Karakoram Pass threatens China’s vital passageways that go all the way from Kashghar to the Khunjarab Pass on the one end and to Lasha, passing Aksai Chin, on the other. It is also threatening for China that India may attempt a feat of occupying Aksai Chin and the Shaksgam Valley in a surprise attack if it finds China non-vigilant, especially, after Indian Ministry of External Affair’s recent assertion that the whole of Kashmir, including Muzaffarabad and Gilgit-Baltistan belongs to India.

In the wider picture, India’s strategic alliance with the United States; its being part of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD); its historic support for Tibetan autonomy; and its several border disputes with China itself make for the air of open confrontation between the two.

While the US engages China in a trade war since 2018, China has been in a constant strife to ally Southeast Asian and South Asian states with multiple huge infrastructure projects and trade activities so that they stay away from making any strategic partnerships with the US or its allies. Yet India has made an advancement that no other US ally has attempted, by making an oil-exploration deal with Vietnam in Block 128 that is partly inside the ‘nine-dash line’. This and several other defense pacts with Vietnam have brought out India as a fearless aggressor towards China.

The renewed US-India strategic alliance since 2016 has also added a new chapter to the Indian defence strategy. After the 2016 Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA agreement), we see increased Israeli presence in India, especially in the context of counterterrorism against the resistance in Indian-Occupied Kashmir (IOK). India’s abrogation of Article 370 and the recent Domicile Law show India’s urgency in breaking down the Kashmiri resistance and its plan to take over the whole of Kashmir, perhaps not being able to calculate how this would thwart the balance at the tri-junction. Add to this the ongoing Hong Kong protests that have not only been supported vocally by the US, Britain and France, but are also allegedly instigated by them. For China, who sees itself as a regional power, to have an intervention right into a territory that it considers part of the mainland, seems unacceptable.

In February 2020, General Bipin Rawat made a statement that “India is looking at setting up a separate theatre command for Jammu and Kashmir”. This is in addition to India’s flaunting about its naval ambitions around the IOR, which include its activities in the Bay of Bengal; its naval base INS Kohasa on the North Andaman Island that threatens the Malacca Strait; its wish to find overseas bases; and its pompous defense budget — all paint a picture of an India readying for war.

On May 26, President Xi Jinping, during his annual meeting with PLA representatives at the parliament, urged the military “to think about worst-case scenarios” and “scale up battle preparedness”. He also said that the Covid-19 pandemic brought a profound impact on the global landscape and China’s security and development. Just two days later, the Chinese parliament voted to impose national security legislation on Hong Kong. Certainly, if China feels that it is being pushed to the wall by its adversaries, and sees the Hong Kong protests, the trade war, the US-India strategic alliance and the Covid-19 (as a biological venture) all as a pack of one compounded attempt against its economy and sovereign strength, it may think it easiest to balance scores in IOK.

Yet, at this point China has the choice to de-escalate which is what India is hoping for through its diplomatic efforts. India may have been over-ambitious and splashy in words, but it is certainly not ready for war. It is facing the worst economic recession that hit it after 2008. Its banks are crashing and exports halting. And there is news of differences between the Indian military establishment and the Doval/Rawat group, showing internal cracks in the Indian security system, making diplomacy and status quo the best possible scenario for India.

But if China decides to prolong the standoff and remain stationed, then short of going nuclear India may not have the capability of fighting off China from the disputed territories in a conventional one-to-one match.

Published in The Express Tribune, June 12th, 2020.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ