Women struggle with lockdown on the home front

Confined to their homes, they are increasingly vulnerable to gender-based inequalities

KARACHI: Before the lockdown, Farheen*, 36, wouldn’t spend even a single day off from work at home. “No matter what I did, I made sure not to stay home on my day off. I would roam the city, go anywhere, but not stay at home.”

A single working woman, Farheen’s elderly parents and a brother believe her choice of working in the media has ‘corrupted’ her, making her impudent and mannerless.

Spending time out of the house gave her a break from the constant criticism and emotional turmoil. But now, the lockdown has her feeling ‘imprisoned’ and frustrated. “I clash with my family more often and my personal space has shrunk significantly,” she said. “I just want to get away from this suffocating environment.”

Work had been her biggest escape. But now, working from home, she is deprived of that too.

In her case, commuting became an issue. When the pandemic emerged, she switched from public transport to online transit startups, wary of the unhygienic public buses.

“People cough in your face, don’t keep any distance and you can’t even say anything.”

Soon, though, online transit was suspended too, and she was left with little choice but to work from home.

“I thought of buying a motorcycle so I could travel to work on my own, but besides social restrictions, I also feel unsafe travelling alone at night,” she narrated, explaining that she worked the night shift.

“I just want to go out and do anything. Eat ice cream, window shopping, anything. I miss all that. The lockdown took away my escape” she said, adding, after a pause, “But I know it’s unsafe to lift the lockdown. And I know that when it is lifted, I would have to go back to the risks of public transport.”

The impact on women

There are no numbers yet to reflect the magnitude of the ordeal and little research has been done to gauge the impact of Covid-19 on women in Pakistan.

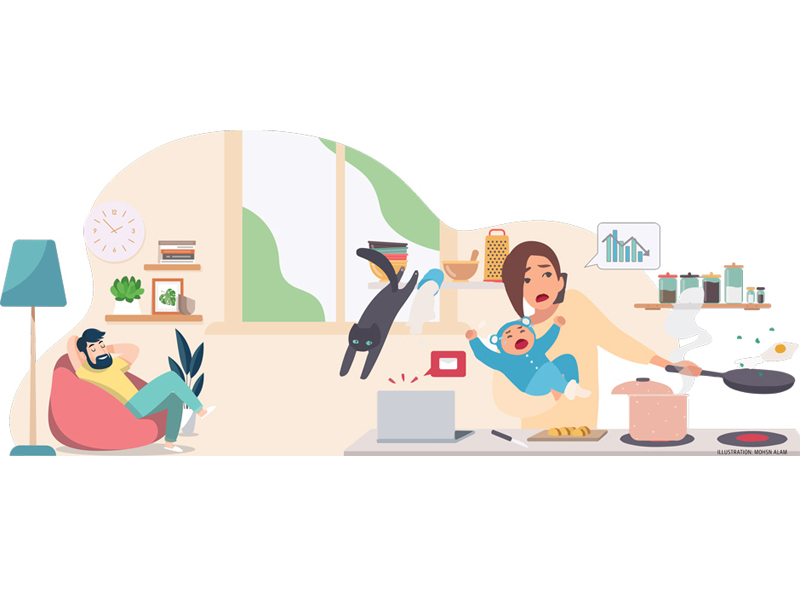

Yet, as the crisis unfolds, it becomes apparent that women will experience its consequences much more profoundly than men. In fact, the pandemic and the ensuing lockdown have been so potent in laying bare gender inequalities that they have already begun to feel the heat.

Confined to their homes, these women and many others in Pakistan are increasingly vulnerable to being exposed to deep-rooted, gender-based power imbalances in multiple ways, taking a toll on their physical and mental health.

“The lockdown is affecting women in particular because in any crises, marginalised groups are most vulnerable and women are one of the marginalised groups in society,” asserted activist Qurat Mirza.

“In our society, women primarily play three kinds of roles: they work in factories and offices, labour in fields and take care of households. But since the lockdown, [most] people have been staying at home, which has increased the burden of care labour on women,” she went on to explain, adding that this meant they were facing the crisis on two fronts.

“They have household responsibilities and have to tend to others’ mood and frustrations, as well as share financial responsibilities,” she added.

According to Mirza, the emotional burden on women, too, has increased during the Covid-19 crisis. “In our society, women manage the household and are connected to everyone in the household. With people not going to work and children to school, women are expected to take care of their emotional needs,” she pointed out.

The activist also highlighted an increase in domestic violence as a result of frustration building up when men are out of work, adding that women bore the brunt of the feelings arising from the financial crunch.

“When there is uncertainty, frustration is directed towards a marginalised segment, which is [mostly] women. I think gender-based and domestic violence – both emotional and physical – will rise further given the impending unemployment crisis, even after the lockdown,” she added.

Working non-stop

While the lockdown appeared to have put the country on pause, Batool*, 38, has found herself working round the clock even at home. A working mother of two living in a joint family, she’s struggling to juggle housework with her eight-hour work shift.

Out of caution, she, too, had asked her househelp not to come to work for now, but this has left her working non-stop.

Acknowledging that men too have been affected by the lockdown, she pointed out that in terms of workload, women had been more burdened. “Cooking and dishwashing is considered a woman’s job, and it’s expected of us to work in the kitchen.” she remarked.

Domestic burdens

Since the lockdown, Samina’s life has been a mess – and her house too.

A resident of Kharadar, Samina’s daughter got married a day before the lockdown was enforced. Now, at home with her husband and sons, she misses her daughter badly.

“Had she been here, she would have been a great help,” said Samina, exhaustion evident in her voice.

Without a helping hand, life has become difficult for the asthmatic woman, whose househelp has refused to come during the lockdown.

Asking her husband for help with domestic chores, too, only lands her in trouble, while her sons are of little help. “One among them is just nine years old, and I don’t expect any help from the older one.”

But this isn’t all that troubles her. Her husband has been out of work for weeks. “He is always angry now, so much so that I can’t even ask him to get bread, let alone ask him for money. If I do, I have to face his rage.”

In her eyes, the virus is nothing but a conspiracy to trouble people. “It needs to end. All of it. My husband needs to go back to work and things need to go back to normal,” she stated emphatically.

Longing for normality

For teacher and single mother of two Hadia*, 44, every day is a new battle in the lockdown.

The sole breadwinner in her family, divorce had already made life difficult, but the lockdown made her hardships much worse.

“Even buying groceries or paying utility bills is a tall task now, leaving me reliant on others,” she said, explaining that she had no transport available. “It’s frustrating when you have to look to others for the simplest of chores.”

At first, she asked her househelp not to come. “But until when? I eventually had to call her because I couldn’t manage the house alone.

At least now I can send her to buy essentials,” she said, adding on a lighter note, “I even told her she is my husband now, bringing eggs, bread and milk for my house.”

But Hadia is still in constant fear of her family contracting the virus, especially her elderly mother, who lives with her as well. “She has been ill and with no means of conveyance, I don’t know what to do if her condition worsens,” she worried.

Not well-versed with technology, she also feared losing her job as classes moved online. Stressed out, she said she had never cried as much as she did now, isolated, homebound and longing for life to go back to normal.

Locked out with nowhere to go

When newly-married Anila, 30, left home for work on March 23, she had little idea that her second marriage was at the brink of disaster, leaving her homeless once again.

Anila, an unqualified nurse, had been providing home care since her first marriage collapsed, supporting herself and her young son. Defying her family to marry a second time, she had move to a rented house with her husband just two days before the Sindh government imposed the lockdown.

As she left for her 12-hour shift, she had hopes of starting life afresh. But her hopes soon came crashing down.

“My employers asked me to stay back and substitute for the nurse covered the night shift until the pandemic subsided,” related Anila, whose limited financial resources left her with no option but to comply.

Her son now stays with her at her workplace while her husband left the city soon after the lockdown, leaving behind no contact information. “My landlord told me that he sold most of my belongings and left,” she wailed. “He didn’t even pay the rent. The landlord has rented the house to another family.”

Work, fasting and the hot weather – not to mention stress – have taken a toll on her. “I get migraines now but I can’t leave work. My husband is gone and I am locked out of my house. I have no roof over my head, no place to keep my son.”

Cursing the virus in Punjabi, her mother tongue, she believed that her life would have been different if not for the pandemic. “Now, even if I wish for the lockdown to end, I know I have no place to go.”

*Names changed to protect identity

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ