Harassment in cyberspace: Online crimes continue to target women in Pakistan

Despite laws, victims refrain from reporting offences because of societal pressures and intimidation from harassers

Maria, a 23-year-old university student from Karachi, had never been afraid of speaking up about women’s issues in Pakistan. Her well-articulated arguments to supports women’s rights were always lauded by her friends, who would often tag her in social media posts related to feminism. And even though her arguments were never meant to be offensive, Maria quickly became a victim of cyber harassment.

“I never thought my opinions would trigger Pakistani men to the extent that they would start harassing me,” Maria, who asked to be identified only by her first name, told The Express Tribune. “Many men started sending me lewd and abusive messages on my Facebook and some of them even copied my pictures from my profile, threatening to doctor them just because they did not agree with my views on women’s rights.”

Initially, Maria decided to seek help and report her harassers to the cybercrime cell, but owing to family and peer pressure, she changed her mind.

“I really wanted to report the culprits for cyber harassment but my mother and female friends insisted I changed my privacy settings on Facebook and stopped openly sharing my views. Even though self-censorship was depressing, online trolls eventually stopped harassing me.”

Maria’s encounter with online harassers is not unique, as thousands of Pakistani urban women are reported to have experienced cyber harassment in one form or the other on a day-to-day basis.

Understanding gender-based interpersonal cybercrime

While there are numerous advantages of information and communication technology (ICT), it can lead to an unpleasant situation, and even gender-based violence, in some cases.

Per the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, gender-based violence – “violence that is directed against a woman because she is a woman or that affects women disproportionately” – includes physical, sexual, and/or emotional harm that has been committed both offline and online. Gender-based cybercrimes include cyberstalking, cyber harassment, and cyberbullying.

Cyber harassment may include acts like sending unwanted sexually-explicit emails, online and text messages, making sexual and offensive advances on people through social networking websites or chat rooms, threatening someone with physical or sexual violence through email or messages, using hate speech against someone which may include hurling insults at someone based on their gender, sexual orientation, or disability and image-based sexual abuse, which is colloquially referred to as 'revenge porn’. It could also include the “non-consensual creation, distribution and threat to distribute nude or sexual images to cause the victim distress, humiliation, and/or harm them in some way.”

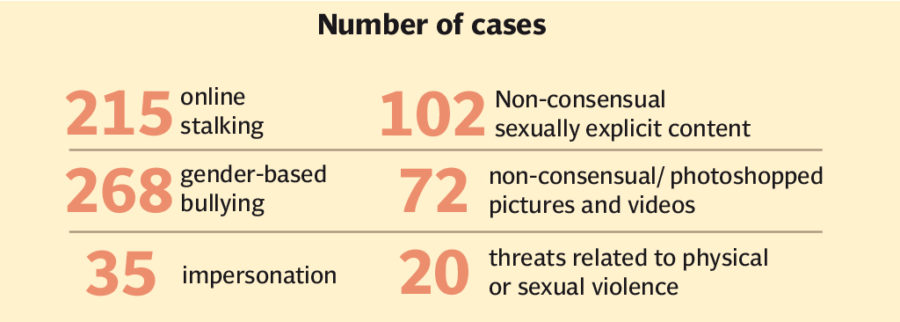

Disturbing numbers

Over the past twenty years, urbanite teenagers and young adults in Pakistan have become significantly social-media and internet savvy. A Global Digital report prepared by We Are Social and Hootsuite shows that as of January 2020, there are 76.38 million internet users in Pakistan, while the number of active social media users stands at 37 million.

Digital experts are of the view that the increasing number of social media and internet users in the country have also led to a rise in cases of cyber harassment, however, most of the cases go unreported.

According to the latest report of the Digital Rights Foundation (DRF), a Pakistani research and advocacy NGO, 40 % of female internet users in Pakistan have experienced some kind of harassment via social media platforms and messaging apps like Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, and Facebook messenger, among others. The report also revealed that despite experiencing online harassment, 72 % of female social media users do not know about cyber harassment laws in Pakistan.

Like Maria, many women also impose self-censorship because of the fear of harassment, so much so that 70 % of women are reportedly afraid of posting their pictures online.

Why don’t women report cyber harassment?

Despite the presence of laws, there are many reasons why women avoid reporting cyber harassment cases. Data collected by the DRF shows that 45 % of women think that it is embarrassing to report online harassment, while 47 % do not report cases because they think it is not necessary.

“The DRF has set up a Cyber Harassment Helpline (0800-39393) in Pakistan for victims of online harassment and violence through which legal advice, digital security support, psychological counselling, and a referral system is provided to victims of online harassment,” the executive director of Digital Rights Foundation Nighat Dad told The Express Tribune. “[Even though] we receive a lot of calls, there are many women who do not report cyber harassment due to societal pressure and norms.”

Explaining the reasons, Nighat said that most women decide to stay silent because of family restrictions and doubtfulness about the implementation of laws.

“A lot of cyber harassment cases, for instance, are related to the non-consensual use and distribution of women’s intimate images and videos, or doctored images that show them in a compromising position. Owing to that, women are hesitant about reaching out for help because they do not trust how their privacy will be handled by the law enforcement agencies,” she said.

Nighat also pointed out that many women reach out to the DRF to seek help but they eventually withdraw their complaints or stop pursuing the case after reaching a settlement with their harassers. Sometimes, women also refrain from reporting their cases when their harassers increase the threats to intimidate them and eventually force them into silence.

Shmyla Khan, program and research manager at the DRF, who also worked for the foundation’s cyber harassment helpline, said that most of the calls she received were related to blackmailing, doctored images, and cyberstalking, adding that many women initially file complaints with the Federal Investigation Agency’s (FIA) cybercrime cell but they eventually give up because of the time-consuming investigative procedure.

“Many women fill the online form wherein they provide details of their ordeals but the cybercrime cell takes a lot of time to get back to them, which makes them hopeless,” she said.

Nighat suggested that a better way to expedite the process is to personally visit the FIA’s cybercrime cell instead of solely relying on the online form, which takes a lot of time.

“If the case is urgent, and the victim cannot wait for too long, they should go to the FIA’s office in person and lodge a complaint. In this way, they can avail speedier service and support.”

Knowing cybercrime laws in Pakistan

As against the common belief that cybercrime laws in Pakistan are weak or ineffective, the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, 2016, ensures strict corresponding punishment for online offences. For instance, spreading false information about a person online can lead up to three years in prison along with a fine of Rs1 million or both. Similarly, doctoring images or making explicit videos of someone can lead up to five years in jail or Rs5 million worth of fine or both. Cyberstalking can result in three years of imprisonment and fines up to Rs1 million while making someone’s videos or taking pictures without their consent and distributing it on the internet and social media can also lead to similar punishment. Hacking someone’s phone or email for the purpose of stalking can also lead up to three years in jail together with the imposition of Rs1 million worth of fines.

Detailing the existing laws, Rabeeya Bajwa, Advocate Supreme Court of Pakistan, said that victims of cyber harassment can make use of different laws to sue the offenders.

“[Apart from cybercrime laws] the state is responsible for protecting the dignity of individuals under Article 14 of the Constitution. When online crimes are committed against women and their identities are threatened by virtue of their gender, their dignities are put at stake,” Rabeeya said. “[Depending on the case] online harassment can also come under the law of defamation.”

She added that if victims of online harassment are compelled to stop stepping outside of their homes out of fear, which, in turn, affects their employment status, then their economic rights are also violated.

Speaking about cases of online harassment where a person is victimised for sharing their opinions, as in the case of Maria, advocate Rabeeya said that such offences also violate a person’s right to freedom of speech and freedom of expression under Article 19 of the Constitution.

“Freedom of speech and expression is a precious right of every Pakistani which is not only guaranteed by the Constitution but it is also guaranteed under the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948, to which Pakistan is a signatory,” she explained. “[Therefore, we can see that there are] several laws in Pakistan that can protect women against cyber harassment, however, there should be more awareness about the laws and victims should be encouraged to report the offenses more often.”

Are there any convictions?

When it comes to implementation and convictions, the picture, unfortunately, does not appear to be so rosy in Pakistan. Recently, the Senate Standing Committee on Information Technology denounced the performance of the FIA and Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) in tackling the growing number of cybercrimes and cases of harassment on social media platforms. According to the committee’s report, out of the 56,000 complaints filed against various categories of online harassment, only 32 of them were under investigation. Lawyers and digital rights activists, however, stress that victims of online harassment should not be discouraged with the numbers and continue to report the crimes.

Speaking about the implementation of the laws, Nighat Dad said that although they take time, convictions of cyber harassers take place from time to time and justice is served.

“Many culprits have been arrested and convicted of harassing women online. In the recent past, culprits were convicted in various cities of Pakistan, including Karachi, Lahore, Peshawar, Rawalpindi, and Gujranwala.”

Agreeing with Nighat, Advocate Rabeeya Bajwa said that Pakistan has the required laws to deal with cases of cyber harassment so women should not hesitate from reporting, adding that the law is on victims’ side [and even though the procedure may take time] women should not shy away from reporting their cases and trust the justice system.

Prevalent digital illiteracy

Even though women in Pakistan have laws to protect them as well as support service like the cyber harassment helpline, digital experts say that just as in real life, it is also important to know more about online spaces, security programmes and privacy settings that can help minimise cyber harassment.

Experts say that many teenagers and young women share their personal lives online without realising that they are putting their information in jeopardy because the warning signs are not always obvious. Therefore, it is also important to distinguish positive and safe sharing from oversharing.

Alina*, a 26-year-old banking professional, whose pictures were stolen from her Facebook profile and used to create a fake account, told The Express Tribune that she had never taken her privacy settings seriously before someone copied her information.

“I never thought anyone would copy my pictures, so I shared everything publicly,” Alina said. “I don’t want harassers and stalkers to get the impression that they have forced me to change my privacy settings, but I would advise other girls to be careful about what they share online and know about a website’s or mobile phone application’s security features. After all, privacy settings are there for a reason, so make the most of it and stay safe,” she said.

Nighat Dad also stressed the need for digital literacy and seeking more information about online spaces.

“Although it is never the victim’s fault if someone misuses their information or starts harassing them online, having information about the internet and social media is very important,” Nighat said. “I always stress women to know more about online spaces, learn to protect personal information from the public, and understand the concept of internet safety and privacy.”

Seeking psychological help

Much like physical and sexual violence, online harassment can also adversely affect a victim’s mental health and well-being. According to mental health experts, victims not only need legal help but psychological counselling is equally important for them.

Shedding light on the importance of counselling for victims of online harassment, clinical psychologist at Bluedot Healthcare and personal counsellor at Sceptre College Tabassum Faruqui said that when a victim is subjected to online harassment or cyberbullying, they can easily become depressed and anxious.

“I worked with a lot of teenagers and young adults – both male and female – who often become victims of cyber harassment,” she said. “As youngsters increasingly use social media platforms, their private information and images are sometimes leaked online, which can have a devastating impact on their mental health.”

Faruqui added that owing to a lack of access to mental health counselling in Pakistan, parents should extend maximum support to their daughters and sons if they have been victimised online instead of blaming and shaming them.

“Oftentimes, young women and teenagers experience cyber harassment but they are afraid of seeking help because their families are not supportive of the idea of psychological counselling,” she said.

This is exactly what happened with Maria when her mother and friends pressurised her and stopped her from reporting her harassers, which pushed her into depression.

“[Families should develop a trustful and supportive environment at home] so that victims can open up about their ordeals and seek mental health support instead of ending up with depression and suicidal thoughts,” Faruqui concluded.

*Some names have been changed to protect the privacy of the victims.

1724319076-0/Untitled-design-(5)1724319076-0-208x130.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ