The forgotten origin of Maula Jatt

A hero popular today for violence, but only a few know that this blood-drenched brutalist was created by a humanist

ART WORK BY WASIQ HARIS

This is why Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci warns us of intellectuals and storytellers he deems as ‘traditional’, since they reinforce society’s existing worldview without questioning its flaws. Modern examples are narratives such as American Sniper (2016) and Black Hawk Down (2001), where ironically, the invaders are the heroes, and the natives are the villains. A picture upside down, convincing its American audience to keep playing along.

Conversely, Gramsci advocates for ‘organic’ storytellers who shatter such reassuring lies by showing society a reflection of itself, through narratives that state harsh truths no matter how inconvenient. One such narrative is Maula Jatt’s little-known origin. A hero popular today for violence, few know that this blood-drenched brutalist was created by none other than a humanist.

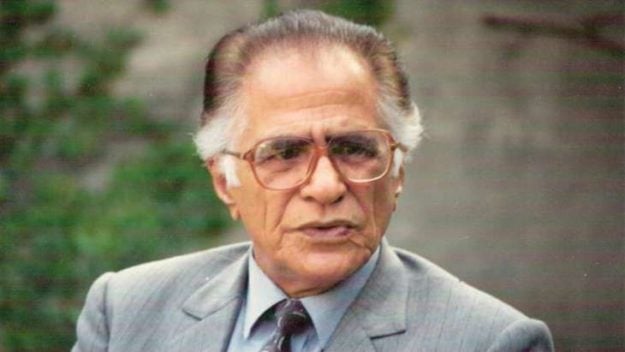

A legendary author, who spent his entire career denouncing bloodshed. Awarded the Tamgha-e Husn-e Karkardagi, Pakistan’s prestigious prize honouring the most distinguished cultural contributions, Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi conceived Maula in a pre-Zia Pakistan for an entirely different purpose - his published story called Gandasa. His Maula was the mirror opposite of what became cinema’s Maula. Those 1970s films borrowed Qasmi’s Maula, not to celebrate it but to hijack it; not to elevate it but to bury its inconvenient truth.

The genesis

‘Gandasa’ begins with a playful Maula receiving dreadful news - the murder of his father by Ranga and his sons. With tears restrained, Maula rushes to catch the culprits. He blocks their path but a village imam intervenes to limit further violence. Preaching that an eye for an eye turns the whole world blind, he compels Maula to let God deal with the sinners.

With great reluctance, Maula lets the culprits pass, but at the cost of making his mother livid. She shouts at him for letting them go, questioning whether he’s even her son, forbidding him to mourn for his father on her shoulders. His repressed tears swapped with shame, Maula vows to wipe the embarrassment from his mother’s eyes. He picks up a Gandasa (blade) and rides off on a horse. With cold-blooded diligence, he murders Ranga.

The bloodshed transforms the playful Maula into the feared village badmash (a thug). But what it doesn’t do is quench the mother’s thirst. She refuses to embrace Maula until he has also killed Ranga’s sons. So Maula pushes himself further to prove his worth. He murders one of Ranga’s sons and starts patrolling the village looking for Ranga’s last son - Ghulla.

Fearful villagers scramble at the sight of Maula, until one day a feisty woman doesn’t. Rajo is a visitor who hasn’t put a face to Maula’s infamous name. Her whimsical words afford Maula a breath of fresh banter. Amid this playfulness that has become all too rare for Maula, he sees a sister in Rajo, albeit she sees nothing in him.

In the end, Ghulla ambushes Maula with a slap and then tries to escape, but clumsily falls right beside Maula’s feet. With the mother witnessing the opportunity unfold, Maula raises the gandasa to ease his final burden, casting a deadly shadow over Ghulla’s horrified face. Suddenly... Maula freezes... because he’d learned that Ghulla was engaged to none other than Rajo.

With his gandasa frozen, Maula tells Ghulla to get up and be on his way. The shocked mother can’t believe her eyes. She shouts and screams, questioning how Maula could be so weak. In this final moment, Maula drops and bursts into tears. “You’re crying?” the astonished mother asks. Maula responds, in a trembling, boyish voice “Can’t I even cry?”.

Qasmi's central idea

Gandasa is Qasmi’s commentary on vengeance and masculinity. He writes it in an era where Indo-Pak wars up till the 1960s are transforming male role models into militaristic heroes. Soldiers are glorified in school books.

Martyrs are celebrated on billboards. Noor Jehan sings, “These sons aren’t sold in any shop, they are brave lions, they can’t be defeated by anyone” and “That is such courage of those mothers, they are the sons of them.” The mother’s relationship to Maula is an allegory for the nation’s relationship to its sons. It suggests that our sons mustn’t just protect and defend, they must also avenge.

They must prove their patriotism through a deadly response that reasserts our dominance. Qasmi gives his protagonist the unusual name ‘Maula’ - meaning lord - because, despite the imam’s advice to leave it in God’s hands, he delivers death to become the one who all must fear.

In the end, he finds himself torn; neither God nor man. A household weapon struggling to be either. With that picture of a tearful eye, Gandasa is Qasmi’s response to “boys don’t cry” - the nation’s reassuring lie.

Let’s address the elephant in the room. Why should we not respond to the enemy’s attack on our soil? When the time to defend has passed, should we not even answer their monstrosity? I question that a lot. But no matter how much I try, what I can’t question is Qasmi’s point of Maula. That avenging the enemy’s inhumanity by doing the same to them renders us inhuman, too.

Despite how we justify our reactions, the moment we unleash the same pain onto their loved ones that they inflicted onto ours, we’ve lost who we are. So what are we fighting for then? A right to be another monster? What are we perpetuating this feedback loop of pain for? To grapple with such questions in the face of pain is what makes Qasmi’s truth so inconvenient. And perhaps it makes sense for those who cannot challenge their worldview to scratch the itch with a traditional answer - vengeance.

The screen takes over

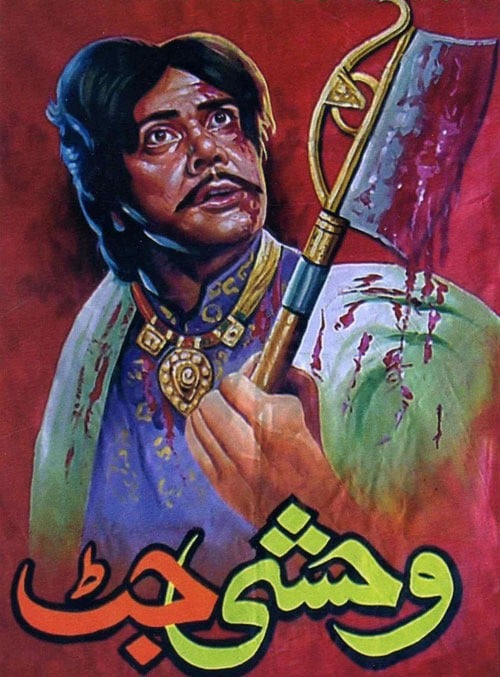

Wehshi Jatt (1974) - the first Maula Jatt film - also begins with a playful Maula learning of his father’s murder. It also leads to Maula intercepting the culprits. But like a ‘brave lion,’ Maula cuts up half of them immediately, stabbing one to death. Being the courageous son, he proceeds to slash the rest of the neighboring clan for the rest of the film. There’s no mother daring him. There's no shame pushing him. There’s no need. In essence, the film ‘fixes’ Maula into what a son ought to be - an instrument of war.

Just like Qasmi’s original, Maula’s gandasa freezes at the end of Wehshi Jatt as well, followed by him also bursting into tears. The difference is that it happens after Maula has already killed every neighboring clansman. Every single one, except the blood-drenched villain, fallen by Maula’s feet.

With guts slashed open across a lifeless body, the villain is taking what may be his last breath, right next to his little son who begs Maula for mercy on his knees - like one begs a god. And then, in a vicious act of kindness, Maula tells the villain to get up and be on his way.

Like a butchered artifact from Qasmi’s original, the sequels repeat the exact same crying at the conclusion of every film, but only after Maula has stabbed everyone to become the victor. Where Qasmi named his story after the frozen gandasa, the films fix it into a bloody one. Where Qasmi named his protagonist the philosophical ‘Maula,’ the films add a sensational ‘Jatt’ to it.

Where Qasmi gave birth to Maula’s character, the films murder it with a doppelgänger. Ironically, the most famous dialogue from the films proclaims:

"Maulay nu Maula na maray, tay Maula nai marda"

"Maula can’t be killed unless killed by Maula"

Beyond Pakistan

The crime at heart is perversion. Maula glorifying vengeance is like Big Bird selling weed. It's upside down. But such perversion isn’t just a Pakistani issue. It's a global phenomenon. Perhaps the best example is Maula Jatt’s spirit animal - Godzilla. Written after WWII, the original Gojira - meaning Gorilla-Whale - is a 1954 Japanese film about the effects of the nuclear bomb on the Japanese psyche.

With a radiation-induced creature terrorizing Japan in the backdrop, traumatized characters depict fear of the unknown aftereffects of nuclear radiation inflicted upon their people. Gojira is an allegory for trauma in a post-war Japan, just like Gandasa is an allegory for vengeance in a post-wars Pakistan.

When the time came for an American release, Gojira’s western distributors re-edited the entire film to fit their society’s worldview. Scenes with the radiation human toll were deleted to shield Americans from the inconvenient truth. Raw, quiet scenes about trauma were overly sensationalized with music.

New footage of an American reporter commentating on the creature was added to shift the focus from the psychological to the superficial. The film received a sensational new name - Godzilla: The King of Monsters. With the human drama sucked out, all that was left was a giant monster stomping on buildings. Just like all we’re left with is a fat badmash stabbing villagers.

Traditional narratives succeed faster simply because their worldviews correspond with the audience’s existing one. They don’t risk challenging concepts like what makes one a hero or a villain because their priority isn’t society’s welding. It’s profiteering. Their successes embolden even more cash-hungry narratives following their footsteps, perpetuating society’s feedback loop.

Like Godzilla’s sequels, Wehshi Jatt’s sequels also introduced bigger, badder monsters to justify the need for Maula’s monstrosity - i.e Noori and Dara. The following plague of emboldened films glorified even more vicious heroes gutting even more vicious villains. An eye for an eye. Inhumanity for inhumanity. A phenomenon ironically known as gandasa-culture dragged Pakistani cinema into the dark ages.

It’s hard to say if it was the narratives that made our society violent or vice versa. Take a walk through their Zia and Post-Zia eras, and you’ll find the regimes justifying extremism by pointing at western extremism. Fanatics became heroes. Floggings became crowd-pullers. Massacres became righteous. To quote Nietzsche, “Battle not with monsters, lest ye become a monster, and if you gaze into the abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.”

The epilogue

March 2019 - The Pakistani government held a beautiful ceremony to distribute national awards. In a grand chamber filled with glamorous attendees, the loudspeakers called a recipient. When the list of his writing achievements echoed around the historic walls, it emerged that he’d written every Maula Jatt film ever made - including the unreleased one.

As he approached the stage and stood before Quaid-e-Azam’s portrait, waiting to be honored with the prestigious prize, he was proclaimed as being the author behind legends, and a contributor of distinguished narratives to our culture. Then, with flashing cameras, he was awarded the Tamga-e Husn-e Karkardagi.

M. Ali Kapadia is a US-based head of design. He tweets @AliKapadia.

Have something to add to the story? Share it in the comments below.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ