'We have 30 minutes': the night Notre-Dame was saved

Six months on, the cathedral's rebirth is still years away

On 15 April 2019, a structure fire broke out beneath the roof of Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral in Paris. (Photo: Reuters)

Security exercises and false alerts are frequent at the historic place of worship, which has stood on the Ile de la Cite in central Paris for over 850 years.

Andre Finot, a communications official working for the cathedral, is waiting on the esplanade in front of Notre-Dame for a work meeting.

The steeple and spire collapse as smoke and flames engulf the Notre-Dame cathedral (Photo: AFP)

The steeple and spire collapse as smoke and flames engulf the Notre-Dame cathedral (Photo: AFP)It's 6:23 pm.

He goes back inside the cathedral and helps evacuate worshippers, according to a well-rehearsed procedure that was only practised once again 10 days before.

Evacuation messages sound out in several languages but there is no sense of trepidation. Even the priest who is leading the pre-Easter service does not leave the cathedral.

Fifty metres away, in her souvenir stall, Florence Mathieu is also not in the least worried.

She thinks she has heard police whistles around 6:30 pm but assumes that "maybe it is just another abandoned package or just a drill."

"We waited around 10 minutes outside and then we were told 'you can go back inside'," says Michele Chevalier, a 70-year-old and regular worshipper at Notre-Dame.

The service resumes in the darkness, without any microphone. Electricity has been cut.

"And then all of a sudden, we heard the cry 'You need to go out! You need to go out!'" says Chevalier.

Andre Finot had gone back out of the cathedral, reassured that nothing was wrong.

Notre-Dame cathedral 'still at risk of collapse' after fire

But around 6:46 pm he notices grey smoke coming from behind Notre-Dame's famed twin towers. Worried, he looks around the cathedral and sees "smoke that is actually quite thick coming from the spire."

The fire at Notre-Dame could be seen across Paris (Photo: AFP)

The fire at Notre-Dame could be seen across Paris (Photo: AFP)A security guard first notices that something is wrong at 6:18 pm when he sees a warning message on his computer. "Roof of nave-sacristy", it says, followed by code in letters and numbers.

The guard sends a Notre-Dame employee to have a look.

There is no sign of any fire, although the automatic alarm goes off at 6:23 pm, at which point the cathedral is evacuated.

The security guard then contacts his superior by phone and over the course of an 18-minute-conversation, they decide to send someone up to investigate the lattice of wooden beams holding up the roof above the nave.

It's 6:45 pm when the flames are detected.

The security alarm is sounded and the fire brigade summoned at 6:51 pm, with the first firefighters arriving on the scene at 7:05 pm.

By then the fire has already reached the roof. Fanned by a wind from the east, it devours the wooden beams which date from the 13 century and begin to melt the 210 tons of lead in the roof.

The fire engine has to force its way through the crowds on the banks of the Seine River where tourists and stunned Parisians have gathered, united in astonishment and horror at the sight of Notre-Dame burning.

"It was completely full of people taking pictures with their cameras and their phones and we thought 'something is really happening here'" remembers Paris fire brigade corporal Myriam Chudzinski.

She then sees that Notre-Dame is "totally aflame".

Chudzinski, 27, starts to climb up the narrow spiral staircase into the cathedral with 20 kilos of material on her back. She pushes open a door and finds herself staring at "a vision from hell."

"The roof was completely ravaged by flames. By the time we got the hose in place, in less than a minute, the fire had already advanced by a few metres. We had to keep moving back".

French firefighters Myriam Chudzinski (L) and Jerome Demay were among the first to arrive at Notre-Dame (Photo: AFP)

French firefighters Myriam Chudzinski (L) and Jerome Demay were among the first to arrive at Notre-Dame (Photo: AFP)Ariel Weil, mayor of the fourth district of Paris, home of Notre-Dame, has just come out of a meeting at Paris city hall on the other side of the Seine river. He sees the smoke rising over the island on which the cathedral is situated and starts to run.

He is accompanied by Anne Hidalgo, the mayor of Paris and the rector of the cathedral, Patrick Chauvet, then joins them. He is in tears.

Weil's first thoughts are for the people living in the narrow street, which runs alongside the north side of the cathedral.

"We're running to tell the people who are at their windows 'Come down! Get out of the building'. We are hit by a hail of objects, probably glass from the stained-glass windows that have shattered," says Weil.

On the other side of the building, Andre Finot is on the receiving end of "a rainstorm of ash". He has what he admits is a "stupid idea".

"I told myself, I can't let this happen, I'm going to fetch a bucket of water'".

But his mobile telephone won't stop ringing.

"The whole world is calling me but unlike everyone else, we cannot see a thing. From where we are the main facade looks completely fine."

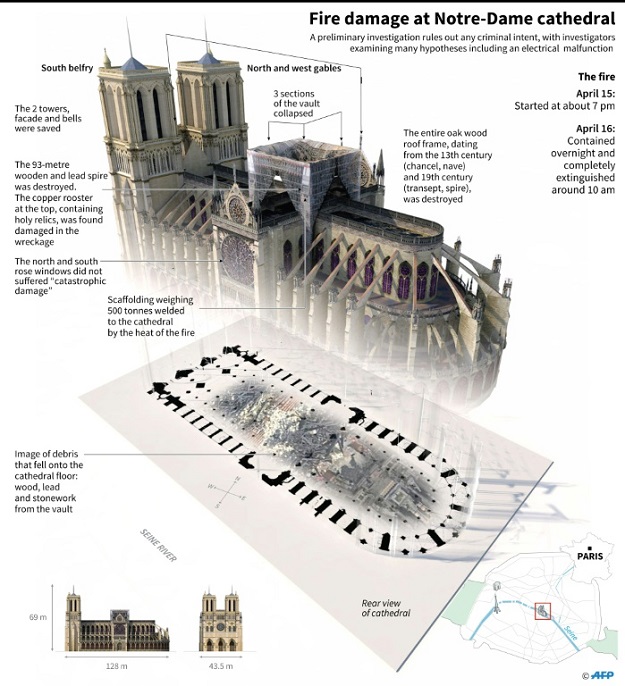

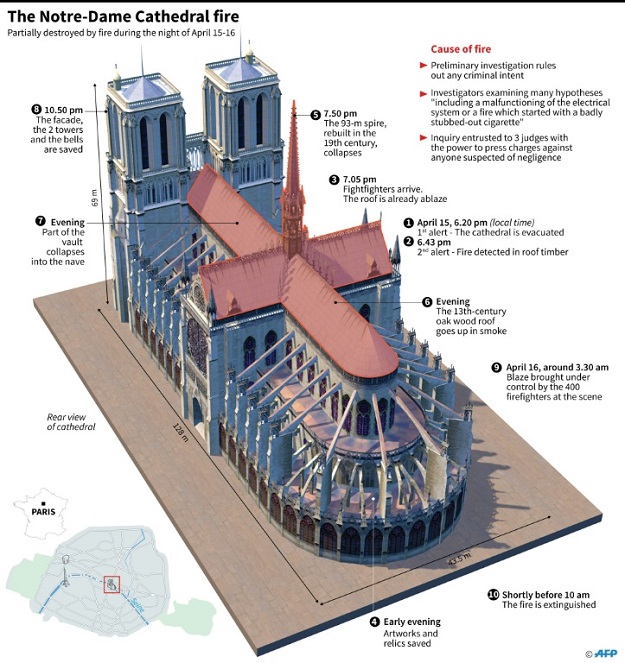

3D illustration of Notre-Dame cathedral, detailing the fire damage (Photo: AFP)

3D illustration of Notre-Dame cathedral, detailing the fire damage (Photo: AFP)What he does not see is that the spire, the highest point of the cathedral, some 96 metres high, is now enveloped by flames.

By now social media is filled with pictures of the huge column of smoke, visible from all over the city, and of the blazing spire.

Around the world, members of the public, politicians and leaders express concern for the famed church, Europe's most visited monument, with 13-14 million tourists every year.

Built between 1163 and 1345 it has survived the French Revolution and two world wars. It has hosted the coronation of Emperor Napoleon and the funeral of several French leaders, including General Charles de Gaulle.

Will it survive the night of April 15, 2019?

At the Elysee Palace, the French presidency has spent the day putting the finishing touches to a long-awaited speech by Emmanuel Macron on his response to the "yellow vest" protest movement.

It has been pre-recorded and is ready to be broadcast on national television at 8:00 pm. But Macron's advisers all agree: now is not the time.

"Given the circumstances, broadcasting the speech would not have seemed right," recalls government spokeswoman Sibeth Ndiaye.

At 7:44 pm it is official - the speech has been shelved.

In the courtyard of the presidential palace, the car engines are running.

The president and his wife Brigitte are heading to Notre-Dame. On the cathedral's esplanade, the crackle can be heard from police walkie-talkies. "Vega [Macron's code name] is arriving."

French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe (L) and French President Emmanuel Macron (3rd L) visited Notre-Dame (Photo: AFP)

French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe (L) and French President Emmanuel Macron (3rd L) visited Notre-Dame (Photo: AFP)On the roof of the cathedral Myriam Chudzinski and her colleagues are struggling to contain the furnace.

Without no view of the entire roof, Chudzinski does not see the spire collapsed. She does not even hear the cry of disbelief from the crowd watching below.

"Because of the trees and the height of the towers the spire was hidden. But we heard the cry of dismay from the crowd and felt the huge emotional weight," remembers the auxiliary bishop of Paris, Philippe Marsset.

In a crowd being kept behind a security cordon on the right bank of the Seine, Florence Mathieu is stunned. "It's just like when the twin towers in New York collapsed. We're wondering what's happening."

Bystanders look on as flames and smoke billow from the roof of Notre-Dame (Photo: AFP)

Bystanders look on as flames and smoke billow from the roof of Notre-Dame (Photo: AFP)As reinforcements arrive from other parts of the city, the firefighters inside the building receive orders to retreat. A total of 600 firefighters will be called up over the course of the night.

As Macron arrives, Jean-Claude Gallet, the head of the Paris fire brigade, sums up the situation.

The roof is lost. What needs to be done now is to prevent the fire from reaching the towers.

In the north tower, there are eight bells weighing each between 780 kilogrammes up to four tonnes. The south tower contains two more bells, including the cathedral's great 17th-century bell Emmanuel, weighing in at 13 tonnes.

If the wooden roof beams fall, taking the bells with it, that would probably be the end of Notre-Dame and there could be casualties.

"General Gallet tells us 'we have half an hour to know if we can save it'. He's not speaking about the roof, he's speaking about the cathedral. At that moment, there is a great silence," says Ariel Weil.

The battle of the belfries is launched. A team of around 20 firefighters go back inside and head for the north tower, with no guarantees for their safety.

Their mission is to put out the flames which are licking at the roof structure, preventively hose down areas that are not yet burning and create a curtain of water between the fire on the roof and the north tower.

The hoses seem puny in the face of the insatiable flames. "It's David against Goliath," remembers Marsset.

3D image of Paris Notre-Dame cathedral with a timeline of the fire (Photo: AFP)

3D image of Paris Notre-Dame cathedral with a timeline of the fire (Photo: AFP)At the back of the building, another battle is underway, to preserve Notre-Dame's precious artworks and relics. These include some of the most important relics of Catholicism.

At 7:30 pm, acting at the request of Chauvet and Gallet, Hidalgo launches a rescue operation. A human chain is formed to carry the works from the cathedral to three lorries dispatched by Paris town hall.

Paris's Notre-Dame to celebrate first mass after fire

"Everyone had the feeling of taking part in a historic, unique moment," recalled Sebastien Humbert, an advisor to Hidalgo.

Thrones, chandeliers, paintings, relics and other precious objects are passed from hand to hand for safe-keeping.

The art experts involved "cradle them preciously, like new-borns", recalls Humbert.

When the operation finishes up around 11:00 pm, General Gallet announces the news that everyone has been longing to hear.

"The main structure of Notre-Dame has been saved and preserved."

Macron insists on taking a look inside.

Molten lead still flows down from the gaping hole where the spire used to be and smoke rises from the jumbled pile of stones and blackened beams that litter the floor of the nave. But at the back, behind the choir, a golden cross shines in the gloom.

"There was a twilight atmosphere," says Andre Weil. "There were ashes and rubble but what was striking was that she [Notre-Dame] was still there, she had made it through."

The altar surrounded by charred debris inside Notre-Dame after the fire (Photo: AFP)

The altar surrounded by charred debris inside Notre-Dame after the fire (Photo: AFP)Many onlookers leave the esplanade, relieved. Members of the fire brigade remain to finish their work.

A little before 3:30 am, the fire is declared to be fully under control even though it is not completely extinguished.

After nearly 9 hours of fighting, agony and prayer, Notre-Dame has been saved.

A view of Notre-Dame cathedral's steeple and spire before, during and after the blaze (Photo: AFP)

A view of Notre-Dame cathedral's steeple and spire before, during and after the blaze (Photo: AFP)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ