But are we finally moving towards an effective and well-functioning local government system?

Let’s compare PLGA 2019 with the 2013 law in terms of representation, powers and resources.

The PLGA 2019 is definitely more representative than the preceding law. The heads of local governments will be elected directly, minimising electoral manoeuvring or election of non-elected members as mayors, as has happened in the previous regime. The newly introduced cabinets will promote shared decision-making. And in institutions like the Punjab Local Government Commission and Finance Commission, the opposition has been given equal representation.

The 2013 law might have conferred more powers to local governments with devolution of health and education, yet these functions remained within the provincial control through administratively managed authorities. The PLGA 2019 has, however, brought the management of schools directly under the local governments. Moreover, the longstanding issue of overlapping jurisdiction has been addressed with development authorities, WASAs and other civic bodies now falling under the local government’s purview, further empowering them.

In terms of resource provision, there might not be much difference between the two statutes. But the PLGA 2019 has introduced the concept of performance-based criteria for a financial award. If done right, this could have a direct bearing on the quality of service delivery.

All in all, the law may not be as ambitious as the district government system of 2001 but is still an improved version of the 2013 act.

But is it sufficient to make the local governments work?

Despite having four laws and eight elections since 1979, we still aren’t clear how a local government should run. Billions of taxpayers’ money have gone into these failed experiments designed on the foundation of political acrimony, vested interests and power struggles.

Let’s face it: for a local government system to be successful, political consensus is far more important than the degree of decentralisation, inclusion or civic participation. Even the best of systems will deliver nothing if they are not given the chance to run. But a flawed system can be gradually rectified if it sustains. With a highly charged and polarised political environment, can the PLGA 2019 stand the test of a regime change?

It is interesting to note that during the last forty years, the local governments functioned for 10 out of 12 years of military rule, all 6 years of civil rule under a uniformed president but only 9 out of 22 years of complete civil rule. Notwithstanding the fact that military-led governments used local governments to create an alternative political base, the political parties cannot be absolved of their responsibility to not let the grassroots democracy prosper.

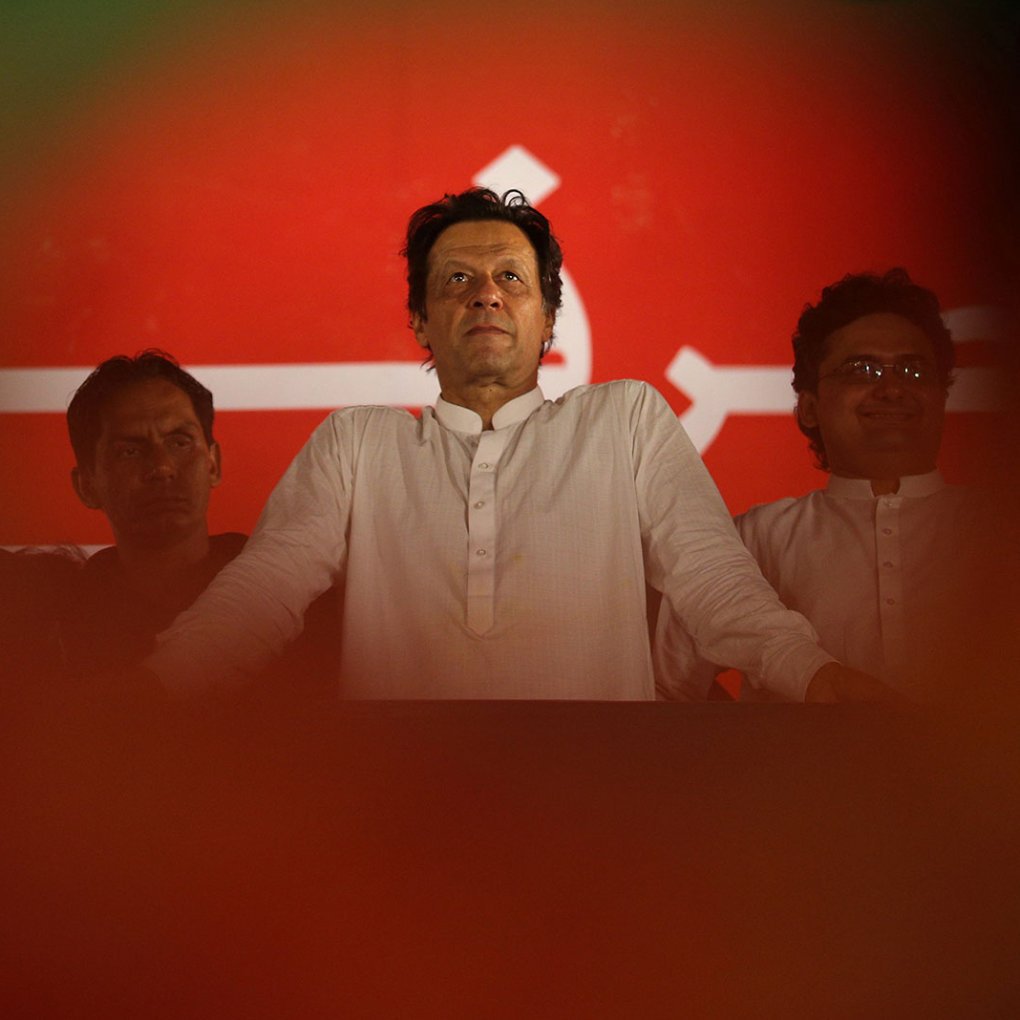

For the PTI, the real test will come with the opposition winning a few large local governments. With direct elections of mayors, it is not merely a possibility but a certainty. Will these opposition-led local governments be allowed to run smoothly and operate with autonomy? This is where most of the past governments had failed.

Whether the PTI will be any different is yet to be seen but the fact that local governments in this country have only flourished under military rule serves as a sobering reminder of our weak democratic values.

Published in The Express Tribune, September 17th, 2019.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

1729662874-0/One-Direction-(1)1729662874-0-405x300.webp)

1722421515-0/BeFunky-collage-(19)1722421515-0-165x106.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ