Scientists create 'all white' albino lizards

This scientific creation will help to understand vision problems in humans with albinism

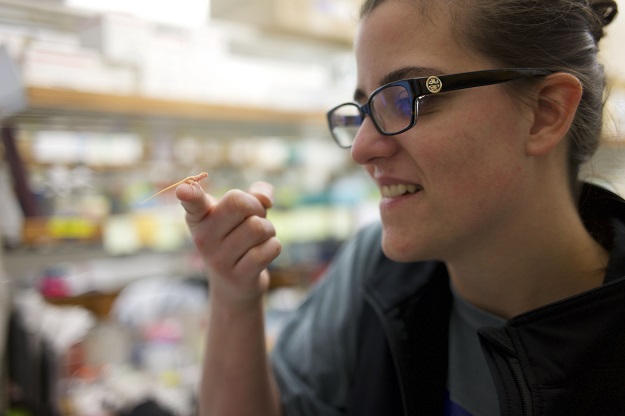

This scientific creation will help to understand vision problems in humans with albinism. PHOTO COURTESY: UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA

A team of scientists at the University of Georgia has now overcome these challenges to successfully make albino anole lizards, and say it could help us better understand vision problems in humans with albinism.

"For quite some time we've been wrestling with how to modify reptile genomes and manipulate genes in reptiles, but we've been stuck in the mode of how gene editing is being done in the major model systems" said Doug Menke, co-author of a paper that described the work in Cell Press on Tuesday.

Scientists a step closer to saving northern white rhino from extinction

Major model systems refer to organisms commonly studied in the lab like mice, fruit flies and zebrafish.

CRISPR gene-editing is usually performed on freshly fertilised eggs or single-cell zygotes, but the technique is difficult to apply to egg-laying animals: For one thing, sperm gets stored for a long time inside the oviducts of females and it is difficult to know when fertilisation will occur.

But Menke and colleagues noticed that the transparent membrane over the ovary allowed them to see which eggs were going to be fertilised next, and decided to inject the CRISPR reagents into them just before this occurred.

PHOTO COURTESY: UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA

PHOTO COURTESY: UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIANot only did it work, but, to their surprise, the gene-edits ended up in both the maternal-line and paternal DNA, not just the former as they had predicted.

But why did they choose to make the lizards albino?

First, said Menke, knocking out the tyrosinase gene, which results in albinism, is not lethal to the animal.

Secondly, humans with albinism often have problems with their vision, and researchers can use the index-finger-sized lizards as a model to study how the gene impacts the development of the retina.

Ancient monkey skull reveals secrets of primate brain evolution

"Humans and other primates have a feature in the eye called the fovea, which is a pit-like structure in the retina that's critical for high-acuity vision. The fovea is absent in major model systems, but is present in anole lizards, as they rely on high-acuity vision to prey on insects," Menke says.

The team says the technique could also be applied to birds, which have been gene-edited in the past but using more complex processes.

Since bursting onto the scene more than a decade ago, CRISPR (also known by its full name CRISPR-Cas9) has been used for a number of potentially game-changing applications: from reducing the severity of genetic deafness in mice to controversially making human babies immune to HIV.

Menke argued it was essential to expand the scope of animals on which the technique could be applied.

"Each species undoubtedly has things to tell us, if we take the time to develop the methods to perform gene editing," he said.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ