Behind the veil all are women

Stories that provide a voice to those who are not always heard.

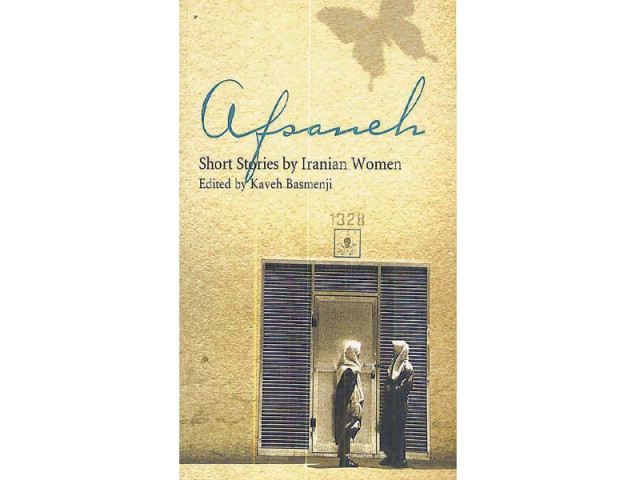

Book: Afsaneh — Short stories by Iranian Women

Edited and translated by: Kaveh Basmenji

Genre: Fiction

Publisher: Saqi Books

Excerpt:

“We went to Karbela, we begged of Imam Hossein to have kids. God gave us Robabeh. It was the year after that Haj Esmail went to work one morning but didn’t come back in the evening. As simple as that the big fellow went missing. Mrs Principal, the security, the police all searched for Haj Esmail. I myself hugged Robabeh and went from one office to another, but it was as if there never had been a Haj Esmail; he disappeared. I would put Robabeh to sleep and sit on my own, smoking opium. I had made Mrs Principal’s cat addicted to opium; as soon as the smell of opium rose, she came and set by me, closed her eyes and snored. I blew smoke at her; she twisted and turned. The cat died of natural causes. Then I made a spider addicted. It had woven a web in the corner of the room. As the smell of the opium rose, it would come down and not move from near the brazier. The coal tong fell on it. It died too.

Women in Iran started entering into the literary arena in the 1930s during the rule of Reza Shah Pehlavi. Prior to that, the land of Persia has been associated only with the famous Arabic mythical story teller Sheherezad of the book Arabian Nights.

The 1960s witnessed the emergence of 25 women writers against 130 male authors. In the 1990s, the ratio of female writers increased tremendously taking it to one to 1.5 against male counterparts.

Kaveh Basmenji is known for translating western literary work into Persian and has worked for Reuters. His publication includes Tehran Blues: Youth Culture in Iran. In Afsaneh he has picked up stories from both the pre and post-revolutionary era. However, the stories are united by their portrayal of women characters blighted by solitude and desperation of one kind or another, leading estranged lives in a male-dominated society.

This also unifies them with the women of the sub-continent. In terms of their thoughts, deeds and actions…their affection for their children, love for their husbands and their efforts to have a peaceful life, they are no different from us. A couple of stories are based on childhood tales focusing on fondness with objects and people. Like in “The Shemian Bus”, a girl shared her liking for a bus driver against the directives of her parents. The story revealed how she called the driver through a heart-to-heart talk and how his visit cured her illness, without the knowledge of her parents. She recalled the story, while standing at a bus stop with her own daughter.

Afsaneh starts with the loneliness of old age. The story titled “To whom shall I say hello” focuses on life without a loving husband, money and a departed daughter who was married to an irrational husband and surrounded by an orthodox mother-in-law. The fantasy to have a happy daughter, a loving son-in-law and lots of relatives and associates ended with an accident. “Grandmother” is a similar tale of a distressed mother — a story of misfortune.

The stories from cities have their own essence while those of exile and those from rural areas add variety to the collection. The story of a dried river that resulted in the end of livelihood of many families in a village is retold by a woman from one of the families in “O’baba O’baba”.

Some of the stories are extremely catchy and end with heart throbbing punch lines and for some, the excitement lies in the ambiguity.

In “A house in heaven”, a woman was rendered homeless during war and wished to die because of she had no place to settle. The story “Secret” unveils the anguish of a cancer patient, when nature imprisoned her with war ridden patients. “Garden of sorrow” shows the pain and agony of a father’s death and the remarriage of a lovely mother. Under such circumstances, tranquillity was found in a deserted garden where a little girl dared to have eye contact with a huge snake. The clash of two approaches; a modern Irani woman and a moderately religious couple can be witnessed in one small cabin of a train, well planted in “Khorramshahr—Tehran”.

It’s believed that if Islam is practiced in its true spirit, women would be more contended. But, unfortunately a woman’s life, since birth is filled with misery and sorrow. Even today, through religious, political and social upheavals, she has exchanged her misery with dreams and fantasies, to find tranquillity. The story of independence at the cost of chastity, dignity and honour can be witnessed in “My mother behind the glass”.

Then there are stories such as Midnight’s drum, Stranger and The blue ones that are not at all surprising for the readers of the subcontinent, as they go through similar cultural and social turmoil. But still there are some interesting facts about the Iranian lifestyle and family set up which can be fascinating for any reader regardless of the background. For instance the love for water melon and the selection of a perfect piece being an art can be seen in “Dahlia”. In the collection the myths of mermaids and the aftermaths of war are the most enchanting events that make the book an interesting piece to read.

Published in The Express Tribune, June 25th, 2011.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ