After a child's dire diagnosis, hope and uncertainty at the frontiers of medicine

According to research firm GlobalData Plc, worldwide sales of many targeted treatments topped $28 billion last year

“Why, my love?”

“Because it’s no good,” he said, pulling at the nearly lifeless fingers of his left hand with its stronger partner.

Already weary from fear and worry over Natan’s cascade of symptoms, I was pained to hear him describe how his body was betraying him.

It was March 2017. Over the previous year, the signs had mounted that something was wrong. First, Natan’s voice weakened. He repeatedly fell ill with lung infections. Each passing week seemed to bring a new warning. He choked when eating or drinking. His left foot dragged. He would trip and fall at play. His eyes moved rapidly from side-to-side. When we spoke to our bright boy, it was harder to connect, as if a heavy fog had settled between him and the world.

Now, Natan was days away from a delicate surgery to remove part of a tumour that doctors had eventually found growing, weed-like, from his spinal cord. It had invaded his brainstem and beyond, slowly suffocating the nerves that control breathing, swallowing and movement. Left unchecked, it could kill him.

But even if successful, the surgery would be only a stop-gap measure, a starting point in a process that would propel our family to the forward edges of medical science. There, the genomics revolution, as it’s known, has made it possible to understand and confront what drives some cancers and other diseases. With tissue taken from a tumour, doctors told us, they would determine whether it was caused by a rare genetic mutation, which could radically change the course of his treatment.

Just a few years earlier, that course would have been grimly straightforward: more than a year of chemotherapy that might stop a tumour from growing. Patients like Natan might need to repeat this punishing treatment several times in childhood and face a life of increasing impairment as the mass robbed them of their ability to breathe or walk on their own. Now, we were told, there was a slim chance Natan could beat back the tumour by merely swallowing a pill twice a day, with few, if any, side effects.

Natan is pushed on a swing by his mother, Reuters' US Health Editor Michele Gershberg, in a park in Brooklyn, New York City, US. PHOTO: REUTERS

Natan is pushed on a swing by his mother, Reuters' US Health Editor Michele Gershberg, in a park in Brooklyn, New York City, US. PHOTO: REUTERSIn the 15 years since scientists completed the first map of a person’s genome – the sequence of DNA molecules that are the unique genetic blueprint of every individual – the process has become steadily faster and cheaper. With the information such testing yields on tumour cells, researchers are developing drugs to target, one by one, specific disease-causing genetic abnormalities, prolonging and improving the lives of tens of thousands of people whose illnesses were once a death sentence. And they’ve only just begun.

“Forty years ago, we didn’t understand cancer, and we didn’t understand the drugs,” said Dr Richard Schilsky, chief medical officer at the American Society of Clinical Oncology. “Now we are actually able to study a patient’s cancer, gain some insight into what is driving it, and in some cases, identify well-established, effective therapies that can target those drivers. That’s a huge difference.”

These advances also bring new risks to patients, already dealing with a devastating diagnosis, who may be encouraged to consider costly new treatments with little evidence of their effectiveness or safety. It is a subject of debate in the cancer community: How to temper the hope for a few against the likelihood that most patients will still not find an answer in these therapies.

“The majority of people do not benefit, but some do, and that’s what’s driving the field forward,” Schilsky said.

Virtual reality helping children fight fear of medical treatment

In Natan’s case, we learned that in a clinical trial, one of the newer targeted therapies approved to treat aggressive adult cancers had worked wonders on a small group of children with similar slow-growing tumours. If DNA sequencing turned up the relevant mutation, the experts told us, Natan would be a candidate for the drug.

I was not about to unquestioningly embrace a treatment on scant evidence, and one whose long-term effects weren’t known. As US health editor for Reuters News for several years, I had worked on articles chronicling the promise and disappointments of so-called precision medicine. I knew to question claims about new drugs that “melted away”tumours.

The professional was now personal, so I and my equally sceptical husband set out to learn as much as we could about the options for Natan. We consulted with family and friends in the medical field and tapped referral networks in our Jewish community. We interviewed experts and read what research we could find. It was exhausting, especially on top of the emotional and physical toll of caring for a sick child, but we had no choice.

Our little boy’s survival was at stake.

Reuters' US Health Editor Michele Gershberg talks with her son Natan in a park in Brooklyn, New York City, US. PHOTO: REUTERS

Reuters' US Health Editor Michele Gershberg talks with her son Natan in a park in Brooklyn, New York City, US. PHOTO: REUTERSNatan was a healthy baby and toddler, active and mischievous at play with his older brother. Our only complaint was that he frequently woke during the night, but in those years, there was always a reasonable explanation: feeding, teething, growth spurts.

Our first real panic struck in the spring of 2016. Natan, then 3, woke one Sunday with a runny nose, but he otherwise seemed fine. I left for the gym. Within that hour, he spiked a high fever, and when I returned, my husband was holding him over the bathroom sink, splashing cold water on his face.

“He went limp, like he wasn’t breathing,” he said. “I’ve called an ambulance.”

After a few days in hospital being treated for pneumonia, Natan bounced back. The speed of his deterioration worried us, yet it seemed similar enough to other parents’ stories about scary but treatable respiratory illnesses in young children and our own preschool bouts with pneumonia and bronchitis.

Soon we began to wonder why his sleep was still so disrupted, and why his voice had begun to sound soft and hoarse.

The first doctor visits turned up nothing unusual. When anyone recommended more in-depth tests, such as a sleep study, my husband and I, wary of unnecessary medical interventions, would ask what practical difference the information could make.

AKUH, Children's Heart Foundation team up for children's health

Within months, it became clear that we needed more answers. When Natan returned to preschool in September, his voice was barely audible to his teachers. He would sometimes appear to choke while eating or drinking. An ear infection gave way to a sinus infection which gave way to bronchitis. When he finished a course of antibiotics, he was soon back at his paediatrician’s office or the emergency room, struggling to breathe.

“There’s no reason a neurologically normal child should sound like that,” a pulmonologist said after listening to just a few breaths.

From Thanksgiving on, the tests began to pile up, as did the medications Natan needed daily. The list of “complaints” on his chart grew longer after each visit: noisy breathing, sleep disorder breathing, chronic bronchitis, asthma. He was hospitalized again for pneumonia at Christmas. Nothing we were doing was making him better, and that helplessness fed our anxiety.

Natan now cried many mornings before school. “I’m sick!” he would say, even if his vital signs seemed normal. At work, I was haunted by the feeling that his teacher or babysitter would call at any minute to say he had stopped breathing. When I picked him up from class, I noticed his heavy gait, how he stumbled forward while walking, and how his eyes seemed dull.

Each new specialist brought in on Natan’s case identified another symptom, now more suggestive of a neurological disorder: the rapid, involuntary eye movements, the weakness on the left side of his body. But we still had no explanation.

“What is the diagnosis?” my husband demanded at each medical visit.

In late February 2017, the two of us sat in the hospital cafeteria, waiting to hear when Natan had roused from the anaesthesia for an MRI scan. We tried to keep our worst fears in check.

“When this is over, we should take the boys to the beach for a month. It’s the best medicine,” my husband said.

I looked at the clock. The call from the nurses’ station hadn’t come in, though more than enough time had passed, and I was antsy.

“Let’s go upstairs,” I said. Then my cell phone rang.

It was the neurologist who ordered the MRI. The scan showed something unusual: a large “infiltrating” lesion centred in the medulla oblongata, the structure at the lower end of the brainstem that controls breathing and other involuntary functions. The thickest part was packed tightly into the cervical spine, with tentacles snaking up into the midbrain and cerebellum, which regulates balance and motor coordination.

“What does that mean?” I asked.

“You need to speak to a neuro-oncologist,” she said, adding that she was trying to get us an appointment within a few days. “There’s no sign of fluid building up in the brain, so you can take your son home.”

“Are you telling me that my son has a massive brain tumour, but should go home now?” I asked.

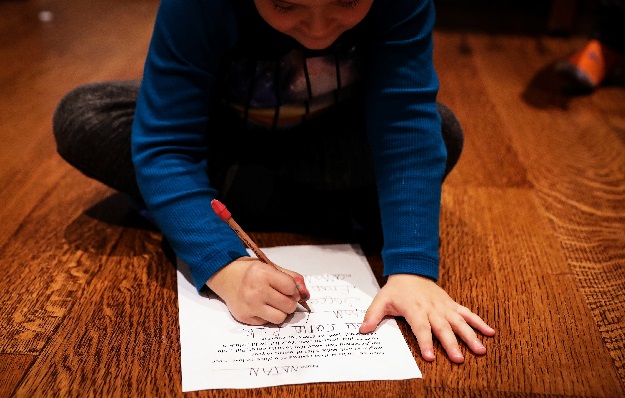

Natan, the son of Reuters' US Health Editor Michele Gershberg, works on his homework in Brooklyn, New York City, US. PHOTO: REUTERS

Natan, the son of Reuters' US Health Editor Michele Gershberg, works on his homework in Brooklyn, New York City, US. PHOTO: REUTERSWe refused to leave until someone who could interpret the scan spoke to us.

An hour later, an expert on pediatric brain tumours told us Natan’s lesion was probably a rare, slow-growing type, appearing in about 100 cases a year in the United States. Natan may even have been born with it, and only now was it large enough to crush the nerves running through his 4-year-old’s brainstem, a structure about the size of an adult thumb that connects the brain and the spinal cord.

These dying nerves were losing their ability to regulate Natan’s walking and fine motor movements, his breathing, swallowing and sleep rhythms.

“At least you now have a diagnosis that explains everything,” the doctor said. “It can take some families much longer to arrive at this point.”

Like many people facing a crisis, we called on every resource we had at our disposal. We were fortunate to have access to excellent doctors and world-renowned hospitals close to home. The health insurance provided through my employer covered nearly all our expenses.

Two weeks after we received the diagnosis, Natan endured a six-hour operation at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Mark Souweidane, director of pediatric neurological surgery at Weill Cornell and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, removed about 20 per cent of a tumour, most of it in the cervical spine. Venturing farther into the brainstem, where a tumour was harder to distinguish from healthy tissue, would have been too dangerous.

Within days, pathology tests confirmed the tumour type: a slow-growing ganglioglioma, a mix of cells that include components of the central nervous system and supporting tissue.

The good news was that such low-grade gliomas are not malignant, meaning that unlike aggressive cancers, they do not grow rapidly and generally do not spread to other organs. In many cases, they stop growing completely when patients reach their 20s. But the large size and the location of a tumour had already significantly damaged Natan’s ability to swallow and breathe. That put him at risk of inhaling fluids and small pieces of food into his airways, leading to deadly pneumonia or choking.

It would take two more months to get sequencing results conducted separately by Weill Cornell and Sloan Kettering, where we sought a second confirmation of the genetic profile of a tumour.

In that time, we focused on Natan’s recovery from surgery, with weeks spent in the hospital and an acute rehabilitation centre.

Removing part of a tumour helped improve some symptoms. The rapid eye movements were nearly gone. In daily therapy sessions, Natan was learning to use his left hand again and walk without stumbling. But we were noticing or confirming new problems: hearing loss, severe sleep apnea, long bouts of hiccups that are a hallmark of brainstem tumours.

I tried to cling to the idea that somehow the surgery would be enough for a few months, or years before a tumour progressed further. I even hoped that it would just stop growing on its own, as a few doctors had suggested, and feared the new surprises he would face in treatment. Even without major complications after surgery, he was fragile, physically and emotionally.

My husband was uneasy about waiting to see if a tumour grew further before starting some kind of therapy.

“It feels like we’re just sitting around waiting for a miracle to happen,” he said. “I want this tumour out.”

The sequencing confirmed that a mutation known as BRAF V600E, most often seen in adults with the deadly skin cancer melanoma, was driving Natan’s tumour.

“I have something for you,” Dr Matthias Karajannis, Sloan Kettering’s chief of pediatric neuro-oncology, told us when we met to review the test results. That “something” was a drug called dabrafenib, sold by Novartis AG under the brand name Tafinlar. It has helped keep a significant percentage of melanoma patients alive after five years when used with a second drug, Mekinist, a great improvement on older therapies.

Karajannis recommended that we use Tafinlar to treat Natan. While chemotherapy is the standard first treatment for low-grade gliomas that cannot be removed surgically, early evidence showed the new therapy could be much more effective.

In some cases, he said, “the tumours just melted away.”

Roche’s Herceptin, or trastuzumab, introduced in 1998, was the first so-called “targeted” cancer therapy, interfering with a growth-promoting protein found in about 20 per cent of breast cancer patients. The drug has improved overall survival rates, particularly among women with earlier-stage cancers.

The next big breakthrough came in 2001, with the approval of Novartis’s Gleevec, or imatinib. Gleevec turned the deadly blood cancer known as chronic myelogenous leukaemia (CML) into a long-term, manageable illness. For nearly all CML patients, the diseased blood cells feature a fusion of two genes that are normally separate. Gleevec blocks the activity of the fused genes and leaves healthy cells untouched — a huge advance on potentially lethal chemotherapy, which is toxic to both diseased and healthy cells.

With Gleevec’s success, the race was on to find other targeted therapies: For each potential new drug, that meant first identifying an aberrant gene that fueled a type of cancer and then devising a drug to counteract that aberration.

The reality is proving far more complex as researchers learn about the multiple influences at work in cancer cells. Many of the targeted therapies approved since Gleevec help only a small percentage of patients with any one type of cancer, and often only for a year or two before their tumour cells create new mutations to outrun the drug.

“There was this feeling we were going to conquer cancer with these approaches,” said Dr David Hyman, chief of early drug development at Sloan Kettering, who leads research into new targeted therapies. Now the medical community has recognized that cancer “is a series of rare diseases,” each with its unique biological mechanisms.

Yet these new drug discoveries can be life-changing for small groups of patients. The US Food and Drug Administration has approved more than 30 therapies that are prescribed based on genomic testing results. Most of these treatments have been introduced to the US market since 2012.

Natan, the son of Reuters' US Health Editor Michele Gershberg, sits on a swing in a park in Brooklyn, New York City, US. PHOTO: REUTERS

Natan, the son of Reuters' US Health Editor Michele Gershberg, sits on a swing in a park in Brooklyn, New York City, US. PHOTO: REUTERS“For many patients, unfortunately, we don’t find the ‘magic bullet,’ but it’s also an area that’s under a lot of development,” Karajannis said in an interview. “Just a few years ago, we had no treatment options.”

A study published in April in the journal JAMA Oncology estimated that 15 per cent of the nearly 610,000 advanced cancer patients in the United States could be considered candidates for treatments informed by genomic sequencing and that close to 7 per cent would probably show some benefit.

Pfizer’s Xalkori and Roche’s Alecensa, for instance, target mutations that occur in about five per cent of non-small cell lung cancer patients. In late November, newcomer Loxo Oncology received US approval for Vitrakvi, a pill shown to shrink a wide variety of tumours driven by TRK fusion, a genetic anomaly found in fewer than one per cent of all cancer patients.

Worldwide sales of such targeted treatments topped $28 billion last year, according to research firm GlobalData Plc.

Within the small community of children with low-grade gliomas, the potential for a targeted approach emerged nearly a decade ago, when two different BRAF abnormalities were identified in these tumours. The BRAF V600E mutation appears in about 10 per cent of the 1,000 US children diagnosed with low-grade gliomas each year. The research coincided with the development of Tafinlar, originally approved in 2013 for melanoma patients with the same BRAF mutation.

At a medical conference in Copenhagen in October 2016, just as we began to investigate Natan’s symptoms, Dr Mark Kieran, then director of the pediatric brain tumour program at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Boston Children’s Hospital, presented data on 32 children treated with Tafinlar.

All the children’s tumours were positive for the BRAF V600E mutation, and nearly three-quarters of them saw their tumours shrink or stop growing on the drug. In two cases, the tumours disappeared, while 11 patients’ tumours shrank by more than half. The side effects were relatively minor – rash, fatigue, fever.

Less than a year later, we read about those results and wondered: Could that be enough proof to use on our child?

My husband and I canvassed as many authoritative sources as possible. We specifically wanted to hear more about treating children with a diagnosis identical to Natan’s: a brainstem ganglioglioma with a BRAF V600E mutation. We reached out to several leading pediatric neuro-oncologists. Some had treated, or followed closely, a few dozen patients like Natan. Others had direct clinical experience with a handful, or none.

They told us that chemotherapy and the new drug were both viable options, but they differed in what they emphasized. Some seemed more supportive of chemotherapy. They cited data collected over decades showing that 25 per cent to 40 per cent of low-grade glioma patients saw their tumours stop growing after chemotherapy, which usually entailed a year or more of weekly infusions of carboplatin and vincristine. Even if the disease returned, a majority of the children survived into adulthood, the studies showed.

Chemotherapy’s potential side effects while a patient was in treatment were harsh, including neuropathy – nerve damage that can cause both debilitating pain and numbness – and the risk of bleeding or serious infection. But there was no cognitive or other long-term damage afterward.

The survival data lumped together many varieties of low-grade gliomas, including tumours cured by surgical removal. Brainstem gangliogliomas like Natan’s represented a very small subset. Newer research and clinical experience suggested that chemotherapy was far less effective in children with brainstem tumours, particularly those with a BRAF V600E mutation, leading to repeat treatments and worse survival rates.

“Do not trust this tumour!” said Dr Eric Bouffet, head of neuro-oncology at the Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto and a co-author on the Tafinlar study. Bouffet was familiar with many of the low-grade glioma patients in Canada. He and his colleagues continue to study their outcomes and track data from other medical centers around the world.

The BRAF mutation appears to make the tumours more aggressive, Bouffet told us during a consultation by phone. He told us about children, like Natan, whose brainstem tumours caused severe sleep apnea, a sudden stop in breathing. One little boy died in his sleep before he could receive therapy, Bouffet said.

Tafinlar’s side effects were much milder, the specialists said, and children using the medicine weren’t missing school like chemo patients. They could enjoy family vacations. But its long-term safety in children was — and still is — unknown and will take years to establish.

The medical literature was also scant. One of the earliest published case studies, from 2014, told the heartbreaking story of a 21-year-old whose brainstem ganglioglioma had returned after multiple rounds of chemotherapy and radiation, leaving him in a wheelchair. His tumour shrank dramatically with Tafinlar, and he began to walk again, only to experience a fatal brain haemorrhage within weeks. His doctors questioned whether the rapid retreat of such a large tumour had contributed to the bleeding.

A second report showed a hopeful outcome for an infant with a massive low-grade glioma that shrank dramatically within two months of treatment, saving her life.

When we consulted with Kieran on Natan’s case, he recommended that we consider chemotherapy first, given its safety record, and if that failed, try Tafinlar. Prior treatment with chemotherapy had also been a requirement for enrolling children in Novartis’s clinical trial.

Natan is given his medication from his mother, Reuters' U.S. Health Editor Michele Gershberg, in the Brooklyn borough of New York City, US. PHOTO: REUTERS

Natan is given his medication from his mother, Reuters' U.S. Health Editor Michele Gershberg, in the Brooklyn borough of New York City, US. PHOTO: REUTERSThere was good reason for caution. Even when drugs are tested on hundreds of patients, safety problems can take years to identify. Now regulators are more willing to approve targeted therapies, particularly those treating advanced cancers, based on testing in smaller groups of patients. For someone with a few months to live and no other choices, the risk may be worth it. But was the trade-off appropriate with a slow-growing tumour?

We wanted to understand why Kieran, who led the clinical trial of Tafinlar, would not recommend using it from the start. In June, as soon as we thought Natan was up for the trip, we took him to Boston. After examining our son and nearly two hours of detailed discussion, Kieran gave a nod to the new therapy.

In a recent interview, he said that when we met, he had just begun discussing therapies like Novartis’s Tafinlar as a first-line treatment with other families, depending on the circumstances of the patient.

“The conversation I would have had with a family five years earlier would have been completely different,” he said. There is enough data now to consider a BRAF therapy appropriate right off the bat for patients like Natan, provided that families recognize that the picture could change as more data emerges, he said.

Not every patient has the luxury of waiting for that information: “You can’t always say, let’s just wait for three years and see how the data goes,” Kieran said. He recently left Dana-Farber to lead pediatric cancer therapy development at Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Through all our research and our consultations with experts, one detail stood out: There was a chance that Tafinlar would actually shrink Natan’s tumour, an unlikely outcome with chemo. If it did, his symptoms could improve, assuming the nerves had not already been irreparably damaged. We needed to give him that chance.

Drugs, kids and dangerous nonsense

Two weeks later, a Sloan Kettering pharmacist showed me how to turn Tafinlar into a liquid for Natan to swallow safely. In our kitchen, I poured the capsule’s white powder into lemonade-flavoured Kool-Aid, which Novartis says is the only drink that can dissolve this advanced medicine. I tried hard not to spill any. Our insurance covered nearly all of the cost, but I was still keenly aware of the expense of replacing just one pill, at nearly $100 retail.

In the first weeks, we kept a close watch for unusual reactions. One evening, Natan nearly passed out for no obvious reason. Another night, his temperature spiked to 105 degrees. It turned out to be a virus. For a few days, hives erupted all over his body. Again, a virus was suspected.

And we noticed something else. After little more than a week, Natan’s voice, nearly inaudible for months, was resonating loudly. At first we doubted that it was real. But Natan was so pleased that he could now hear himself, and talk over his brother, that he would yell and sing spontaneously.

Over the summer, testing confirmed that his hearing had returned. His gait grew steadier and stronger. With a twinkle in his eye, Natan would take an extra deep breath for the nurse and watch the monitor as his oxygen levels ticked up from 99 per cent to 100. He was taken off the respiratory medications and the antibiotics that had been a mainstay for nearly a year.

Natan’s next MRI, in October 2017, showed a result far beyond what we had allowed ourselves to hope: Nearly all his detectable tumour was gone. “It looks almost like a normal brain,” Karajannis said.

My husband and I have asked ourselves whether we could have noticed the symptoms earlier and whether treatment at that stage would have spared Natan from the worst of his illness. But given how quickly the science has developed, we now think the opposite is true in our case: Had we found the tumour earlier, Natan would have most likely endured chemotherapy infusions and their harsh effects every week for more than a year, with little real benefit.

The success of Natan’s treatment provides no guarantees. No one can say how long the medicine will work, whether he should take the drug indefinitely or stop, or whether doing either poses any risk.

The science is also moving on. Novartis is beginning to test Tafinlar plus Mekinist – the combination used to treat melanoma patients – versus chemotherapy in children whose low-grade gliomas exhibit BRAF V600E mutations to see if the combination works better, and longer. The drugmaker has also dropped the requirement that patients have prior treatment with chemotherapy to enrol. A new generation of BRAF therapies from companies including Array BioPharma and AstraZeneca are in clinical trials. Our hope is that if Tafinlar stops working for Natan at some point, a new therapy will be there to take its place.

It’s been more than a year since Natan started treatment. He began to run again, and jump, and swim, and climb. He’s now in first grade, excited to get to school each day and see his friends.

Natan now swallows his capsule with a sip of water, flashing a thumbs-up each time. He has travelled on vacation, even overseas, without mishap. On our last trip, he picked out a new T-shirt for himself. On the front, it says: “Never give up.”

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ