In the Era of #MeToo: Part 2

No one is saying you take their word as gospel, but at least treat it with the seriousness it deserves

#MeToo. PHOTO AFP

Yet, despite the lapse of 27 years, it seems speaking up about harassment and assault has not gotten any easier for women, especially so when the person they are accusing is part of a rank of powerful white men. While the Thomas-Hill confrontation always had racial tension coursing through it, the Kavanaugh-Ford issue brings a relative simplicity: one woman’s accusation against a powerful man. But 27 years later the discourse has barely matured, imagine the trauma when the President of the United States tweets that you’re making the entire thing up. If the allegations were so serious, says the president, why didn’t Ford come forward earlier?

Such questions are all too familiar for women who choose to speak out regarding an incident of harassment that happened sometime in the distant past. It doesn’t matter whether you are a woman in Pakistan or the United States — the same question will haunt you whenever you dare to speak up: Why did you wait? Living in the so-called era of #MeToo, you would think questions such as this would now be moot. Since this is unfortunately not the case, perhaps it is best to once again address this question head on.

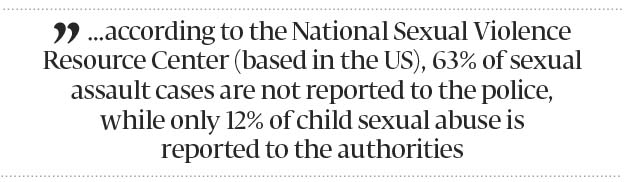

First, it is the trauma of harassment and assault that is the most effective way to make sure a woman stays silent. It is an insidious thing, a vicious cycle. Speaking about harassment means reliving harassment. Reliving harassment in turn causes further trauma, misery and depression. No wonder women bury it deep within the recesses of their mind where dark thoughts lurk. Only an act of overwhelming bravery can bring these thoughts to the forefront to be confronted, over and above, I might add, the bravery needed to continue life with the same vigour after an incident of harassment occurs. Most victims of sexual harassment and assault don’t speak up; according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center (based in the US), 63% of sexual assault cases are not reported to the police, while only 12% of child sexual abuse is reported to the authorities. It is clear that speaking out is an act of incredible bravery, is it too much to ask that we stop asking: why are you telling us now?

The counter-argument, at least from a legal perspective, is that a lapse of considerable time makes the recollection of events by the victim doubtful. According to psychiatrist Dr Richard A Friedman, this issue doesn’t factor in cases of sexual assault. He talks about how the trauma of such attacks actually results in survivors of traumatic incidents vividly recalling the events even after long periods of time. If this is true, who are we to doubt whether the victim’s memory is reliable or not?

Secondly, women often don’t speak out because of the backlash that ensues. Consider Anita Hill, who was referred to as one Senator as scheming to “come out of the night like a missile and destroy a man.” It has become all too easy to label the accusing woman a man-hating attention seeker. ‘Hell hath no fury’ like a woman scorned after all. But such patriarchal stereotyping and cliché lines dehumanise women and rob them of being able to tell their story. Couple this with the fact that women are often harassed by people they know, and you should see why it is so hard to speak out. If you have worked hard for your career, like Anita Hill had, and the harasser is your boss, you learn to take the pain. Nobody wants to be fired. Or the inevitable questioning about how you got the job in the first place? In Pakistan, for example, if you are harassed by a family member and you are brave enough to speak out, well, we all know the gender that most people will side with. Boys will be boys after all.

Which brings me to the most common reason behind why women stay silent: nobody believes them. No one is saying you take their word as gospel, but at least treat it with the seriousness it deserves. Nobody likes being called a liar. Plus, the claim is often dismissed as attention seeking. But ask yourself how does a woman benefit from making a claim of harassment? Actually, which woman has ever benefited? Coming out results in your character, your integrity, your family, your clothes, all coming under constant scrutiny. See for reference: every woman who has ever made an allegation of sexual harassment or assault.

All that women like Meesha Shafi and Christine Blasey Ford ask is that we take their allegations seriously, that we not torment them with allegations of attention-seeking, vendettas and the lack of speaking out in the past. Asking that allegations of harassment and sexual assault be taken seriously does not mean that we believe an accuser and are willing to forego the presumption of innocence, but talking like it is exciting for women to make up accusations of harassment is pure unadulterated baloney.

We should all know better by now, after countless books and papers on the subject of how hard it is for women to speak out, it is time to put an end to this constant question of ‘why wait till now?’ There is now a broad consensus that asking this question is both patronising and patriarchal. You don’t need to be a woman to understand this, you just need to be a human being with empathy.

Published in The Express Tribune, September 25th, 2018.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ