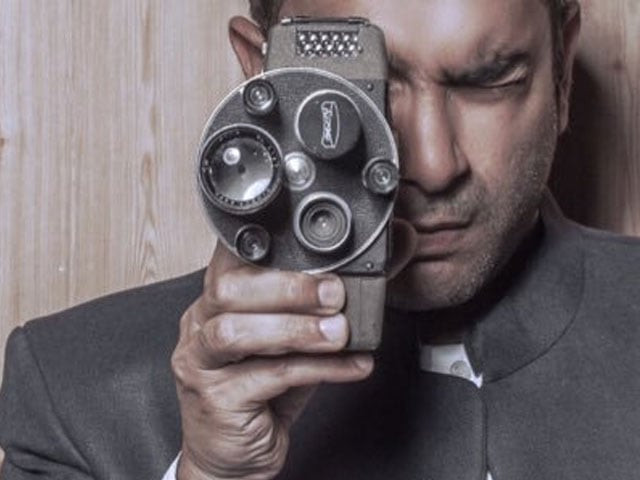

Before 'Humsafar', I’d never done a TV romance: Sarmad Khoosat

In an industry plagued by mediocrity, the ‘Manto’ star has always remained true to his art

PHOTO: PUBLICITY

But very rarely, if at all, does one come across an artiste as involved as him. This was the first time I met Khoosat and his artistic zone was engrossing, to say the least. His performance in the play Mein Tenu Phir Milangi was incredible; the highlight of the three-day event. But it comprised mostly of satirical monologues and subliminal gestures, like using ink as sindoor, for instance.

PHOTO: PUBLICITY

PHOTO: PUBLICITYThis is why most of Khoosat’s work doesn’t appeal to a larger section of society. But last year, he came abloom with four serials (including the televised version of his 2015 feature film Manto) and a supporting role in Motorcycle Girl. Did he consciously plan to work this way?

“No,” Sarmad tells The Express Tribune, in his usual soft-spoken manner. “If you look at Mujhe Jeenay Do or Baaghi, they weren’t long commitments. After Mor Mahal, I didn’t want to direct something abruptly. Acting is less anxiety-causing; that’s the mildest way I can put it. Directing requires a whole lot of responsibility. So I did Baaghi and simultaneously shot for Mujhe Jeenay Do and Teri Raza.”

PHOTO: PUBLICITY

PHOTO: PUBLICITYI can’t help but wonder why the grand Mor Mahal, touted as the biggest drama made by Pakistan, seeking inspiration from the Mughal and Turkish dynasties, failed to strike a chord. Sarmad has given Humsafar, our most successful play to date. Does he feel Mor Mahal was ahead of its time?

“I don’t know if I would want to look at it like that. There is something I can allow people to take-away from my experience and then, there’s something I would just not let anyone take-away and that’s the process of investing myself in a project,” he says confidently. “I’m sure Mor Mahal had its own flaws and maybe, we were not great with it. I’ve never done plays hoping to make hits. Sometimes it works; sometimes it backfires.”

Nonetheless, the veteran actor admits it took a lot from him. “Mor Mahal definitely exhausted me because of its scale. It literally took about two years of my life! But then again, failures don’t scare me,” he adds. “There’s so much of my work that didn’t work but I’ve been very happy doing. I don’t think the Manto serial is a commercial hit but that doesn’t mean one should stop experimenting with their craft or pushing boundaries.”

PHOTO: PUBLICITY

PHOTO: PUBLICITYKhoosat’s Teri Raza also came under fire for its stereotypical plot. How did he wrap his head around that? “TV has become very complex in terms of what works and what doesn’t, both for the audience and you,” Sarmad responds. “Sometimes, the most banal stories work but when you attempt to tell a complex one, it doesn’t.”

Khoosat did, however, decide to take a brief sabbatical from lengthy directorials. “I made up my mind about not doing something which takes so much time on TV because it has a very short-lived memory,” he says.

“Right after Manto, I did Mor Mahal and the idea of working on the two collectively for about five-years frazzled me. Acting is slightly easier that way: you do your work and you’re done. You don’t have to look into the edit and post. You are just a component – not made to feel responsible for everything.”

PHOTO: PUBLICITY

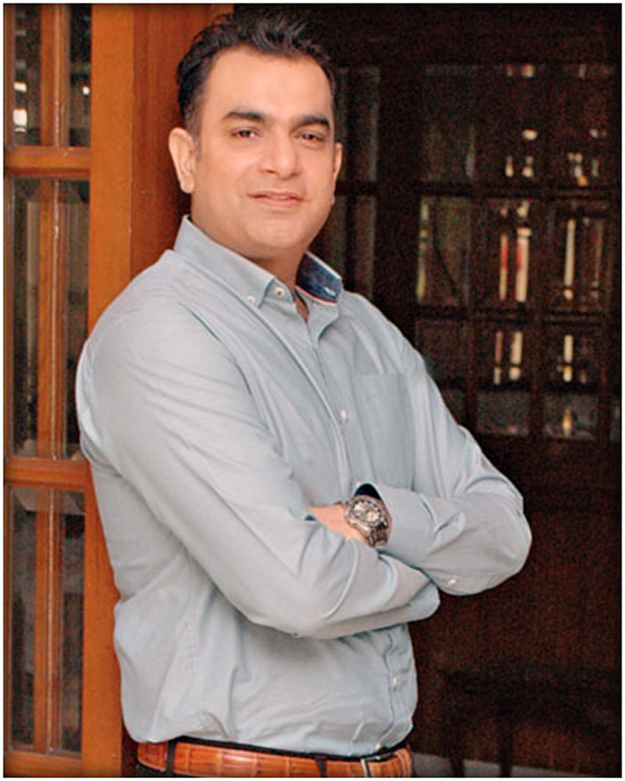

PHOTO: PUBLICITYHaving been to one of his sets recently, I’ve come to one conclusion: nothing remains half-baked when it comes to Khoosat. And his work is testament to that. “Before Humsafar, I’d never done a TV romance. I’m sometimes a little complaining towards the audience, but largely, the different kinds of work I’ve done have found its own audiences; sometimes it’s massive, sometimes it’s small,” Sarmad says, asked about resorting to romantic scripts. “I don’t know if I consciously make that choice. Somewhere in the back of my mind, I knew simpler stories can be good stories when Noorulain came my way. And I did it.”

Pakistani TV is certainly becoming a little braver, though. One can tell that it has consciously not been made too hard-hitting for a larger audience. With those kinds of steps, Khoosat does feel the industry’s paving way for more substantial, progressive and forward content by not beating around the same bush. To him, the idea isn’t to shock the audience but to give it small, real doses.

PHOTO: PUBLICITY

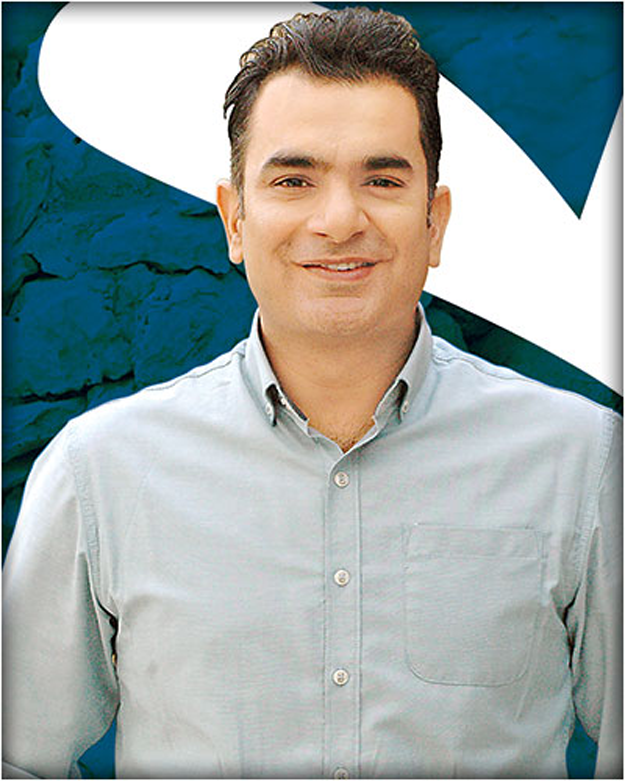

PHOTO: PUBLICITYBut in times where mediocrity continues to sell, how does an artist survive? “TV is fixated on ratings but some unusual stories have popped up and proved that there is an audience that is slightly more prepared for intense content and it’s our job to do something that makes their palates a little broader,” the director explains. “Naturally, people get bored, but there will always be an appetite for mainstream work. Artists cannot take a backseat and say it’s not our responsibility; somebody will have to come forward and challenge the audience.”

Khoosat’s recent choices of work sure seem to reflect that. The mind-boggling Akhri Station dealt with a range of taboo subjects such as prostitution and mental illness, airing simultaneously with Noorulain. But these choices are based on a number of factors, I discover.

PHOTO: PUBLICITY

PHOTO: PUBLICITY“Sometimes, I trust people like Momina (Duraid), who has mastered the kind of storytelling that Humsafar had. Everything comes with its own challenges. It’s not easy to make a Noorulain. And I’d still like to believe that my mainstream work is not repetition,” he continues, of how even his lighter endeavors are far from being fluff. “I try to do something or the other.”

Khoosat admits he considers the monetary remuneration being offered before signing up for a project as well. At the same time, he says some anger has seeped into his art, which helps him get the audience invested emotionally. “This is my profession and you have to look at what pays the bills too,” he states.

“My basic theory is that there are certain kinds of storytelling that are more popular and so, there’s more money in it. But then, something like Akhri Station needs to be done more out of passion and less for the money. And there are also projects like Manto where no matter what I get paid, it would be insufficient.”

PHOTO: PUBLICITY

PHOTO: PUBLICITYWhile a few actors, namely Mahira Khan, Nimra Bucha and Sania Saeed, have remained part of the Sarmad Khoosat coupe, he has been working with a newer pool of actors lately, such as Eman Suleman, Malika Zafar and Ammara Butt from Akhri Station. Khoosat claims he’s ever had trouble choosing stars for his projects.

“Most of the actors that I’ve approached are pretty content. I personally like working with newer people because that’s what keeps it alive,” he shares. “I think monotony is the enemy in this field and when I’m working with actors, I don’t want them to bring their unnecessary egos. Working with a newer bunch makes it more joyous \ because stars do come with their baggage and we need fresh talent.”

Have something to add to the story? Share it in the comments below.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ