A distinguished banker by profession, Yousufi made his appearance on the literary scene in 1961 with the publication of his first book – Charagh Talay – which was a compilation of 12 humorous essays. It was followed by his second book – Khakam ba Dahan – containing eight humorous essays and published in 1969. Both the books being compilation of essays naturally lack thematic integrity except for the thread of humour and wit that runs through these writings. His third book – Zarguzasht – appeared in 1976. It is a fictional autobiography where Yousufi himself is not the main character -- and leaves it to the reader to find out Yousufi from amongst so many characters.

His fourth book, Aab-e-Gum, published in 1990, is a nostalgic account of a generation on both sides of the border who witnessed the Partition and the pains and sufferings it entailed, besides the loss of home and erosion of values and norms. His fifth and last book, Sham-e-Shair-e-Yaraan was published in 2014. It falls short of lofty standards of style and craftsmanship, Yousufi had himself set in his earlier four books. It is a spoken word, lacking Yousufian grace of the written word. It is a compilation of assorted speeches and addresses delivered to a variety of gatherings that suffer for want of coherence and thematic integrity.

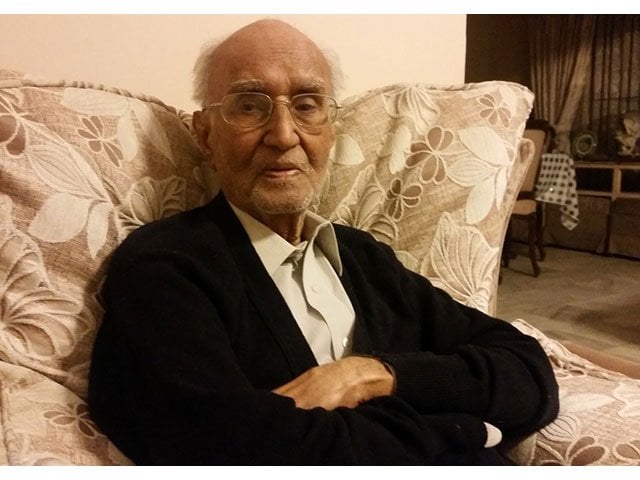

PHOTO: EXPRESS

PHOTO: EXPRESSAre the writings of Yousufi humorous or satirical? Yousufi raises this question in the preface of his first book, Charagh Talay. “I would only say that if the strike is pre-mature or it is half-baked, people will assume it to be a ridicule or satire,” he says and then admits that a simple and well-crafted satire is a hazardous job leaving the author stumbling. “The humour is to shine out of the fire from within. A fire reduces a wood to coal; but if the fire within (the coal) is more than that burns outside, then the coal is turned into a diamond.”

In his writings Yousufi deliberately avoids political or social issues. In the foreword to his second book – Khakam ba Dahan -- Yousufi impliedly admits that his writings are pure and simple humour, devoid of social sensibility, themes or issues. Why? Referring to some criticism that his writings don’t reflect on the current social problems or the political issues, Yousufi retorts: Had the chiding, reproach or censure been successful to reform others, there would have been no necessity of inventing the gun-powder.

Dr Rauf Parekh in his Urdu Nasr mein mizah nigari ka siyasi o samaji pas manzar, also claims that Yousufi avoids not only the political issues but stays away from the social problems as well. Since his only objective is to laugh and make others laugh, social or political issues can hardly find a place in his writings. Dr Muhammad Sadiq in his Twentieth Century Urdu Literature writes that “He has no axe to grind, social or political, and finds humour in everyday experience. His is the subtle blend of humour and wit and it is his wit that gives point to his narrative………..”

Renowned humourist, author Mushtaq Ahmed Yousufi passes away

However, according to Yousufi, a humourist must create a dividing line (a wall indeed) between himself and the painful realities of life in his surroundings. “Humour has its own demands or etiquettes. Foremost of it being that vexations, displeasure or afflictions must not find its way (into the writing); otherwise it will react like boomerang hitting back hard on the writer himself.”

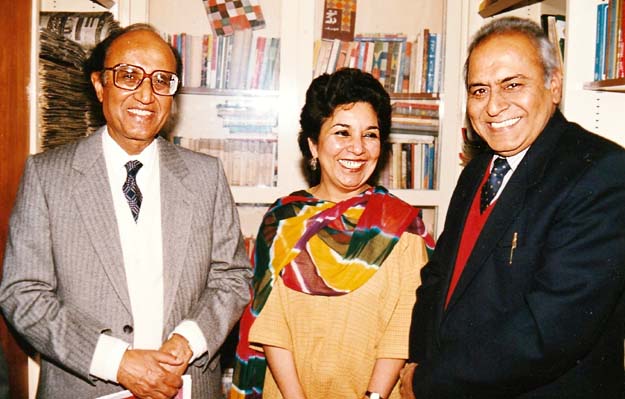

PHOTO: EXPRESS

PHOTO: EXPRESSBut, again according to Dr Parekh, there is one subject that Yousufi is never tired of enjoying and derives pleasure in its mention. That is sex and women. He is always overtaken by ebullience while attending to erotic callings of the subject.

About his autobiographical Zarguzasht, Yousufi claims that it being a story of a common man, is based on his own life. “The events, observations and impressions (in these pages) relate to first six or seven years of my banking career when banking was considered an hounourable profession.” He adds that it consists of some charcoal sketches, some caricatures and a few passionately drawn cameo portraits.

Very little is known about the personal and family life of Yousufi. He never liked to talk about it. Hailing from a Yousufzai Pathan family, Mushtaq Yousufi was born in Tonk state of Rajhastan on August 4, 1923. His father, Abdul Karim Khan Yousufi, was the chairman of Jaipur Municipality and later Speaker of the Jaipur Legislative Assembly. After school education in Tonk he did his graduation from the Agra University, Masters in Philosophy and LLB from Aligarh University. He was selected for the Indian Administrative Service. But the odds were turned after his father while addressing the assembly criticized Indian army action in Hyderabad Daccan. The family had to migrate. Once in Pakistan, Yousufi, on the persuasion of Abul Hasan Isphani, joined the Muslim Commercial Bank to begin a distinguished banking career. In 1965 he joined Allied Bank as its Managing Director, went to the United Bank as its President in 1974 and in 1977 became the Chairman of the Pakistan Banking Council. In 1979 Agha Hasan Abidi hired him as advisor to the Bank of Commerce and Credit International.

PHOTO: EXPRESS

PHOTO: EXPRESSYousufi was not a prolific writer. But he was fastidious and a craftsman par excellence. Style doesn’t come to him naturally. It is achieved after a long laborious process. He writes, rewrites, revises, editing, crafting and refining each word and every sentence, time and again. And this alone explains the long gaps or intervals between his literary outputs. And what finally comes out is a style and diction marked by linguistic twists and turns, incessant play on words, alliteration and inversion of thought. Language conscious as he was, Yousufi got the legendary Shahid Ahmad Dehlavi to go through the draft of his first book while the draft of second was referred to linguist and lexicographer, Shanul Haq Haqqi, to point out follies and mistakes, if any, and to suggest improvements in the text.

Yousufi must have drawn inspirations from many of his predecessors in English and Urdu. He must have thoroughly studied prolific English humourists P. G. Wodehouse and Stephen Leacock. But unlike Wodehouse, Yousufi never detested his banking career or profession. He rather enjoyed it and derives many situations, topics and characters from his long association with the banking sector. He is not even bothered about Joseph Addison’s didactic or reformatory zeal to distinguish between ‘true and false wit’ or between ‘good and false humour’, but seemed to have firmly believed in what Leacock once said: “humour may be defined as the kind contemplation of the incongruities of life and the artistic expression thereof.”

Dr Rauf Parekh traces some other influences. He tells us that Yousufi, according to his own admission, wanted to write the way celebrated Urdu writer Shafiqur Rahman did. And when he could not succeed to achieve that standard, he had decided to give up writing. Dr Parekh also sees the influence of Rasheed Ahmad Siddqui and Patras Bokhari on the style and diction of Yousufi. It is a mix of the two, he says.

Alexander Pope referring to ‘wit’ in his famous ‘Essay on Criticism’ writes:

True Wit is Nature to advantage dress'd

What oft was thought, but ne'er so well express'd;

Something, whose Truth convinc'd at Sight we find,

That gives us back the Image of our Mind:

As Shades more sweetly recommend the Light,

So modest Plainness sets off sprightly Wit:

For Works may have more Wit than does 'em good,

As Bodies perish through Excess of Blood.

Muhammad Sadiq believes that “Yousufi’s wit is seldom lined with thought. Contrary to our expectations, the years have not brought the philosophic mind, and he seldom rises above mere faceliac.” But Yousufi seems to have largely lived up to the standard defined by Pope.

1716998435-0/Ryan-Reynolds-Hugh-Jackman-(3)1716998435-0-165x106.webp)

1730706072-0/Copy-of-Untitled-(2)1730706072-0-270x192.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ