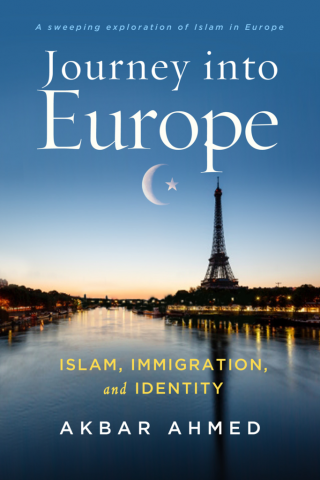

Journey into Europe: An antidote to the Clash of Civilisations

Akbar Ahmed’s latest book takes a deep look at the lives of Muslims living in the West

PHOTO: BROOKINGS

The book is an original and unique contribution to the expanding literature on Islam in Europe for various reasons.

First, as an anthropologist, Ahmed breaks away from the usual solitary work of the researcher consigning his observations into a notebook. Instead, he works with young scholars of different ethnic and religious backgrounds, getting fresh and diverse perspectives on the situation at hand. Secondly, this team work is a great asset for presenting the diversity of Muslim voices in Europe, while most research on said topic tends to shed light on one particular group at a time.

In Journey into Europe: Islam, Immigration, and Identity, the reader will discover a vast array of Muslim figures, from Sicily to Munich, from upper-class Muslims in Berlin to the disenfranchised youth of Bradford, as well as a wide range of identifications to Islam, from secularism to conservatism. The narrative weaves a vast tapestry made different threads and provides a level of nuance quite unprecedented in academic publications.

Also, the book has the unique advantage of presenting non-Muslim religious and political figures that are also part of this tapestry. It is quite unusual to also address the diversity that Muslims interact with, from extreme-right political figures to civil servants and religious leaders of other communities.

By restituting this polyphony of voices, the book is a unique and courageous attempt to display the diversity that challenges the simplicity of the current discourses and policies on Islam and Muslims in Europe. In this respect, the information gathered by Ahmed reveals Islam is not per se the main factor in the building of Muslims’ social identities or in their political participation. Instead, other elements — class and immigration backgrounds, among them — have a decisive influence as well.

PHOTO: PUBLICITY

PHOTO: PUBLICITYConversely, Ahmed also describes parallel simplifications at work among some Muslims who depict Europe as an oppressive and corrupt West. In this sense, the author shows that the clash is not between civilisations but between essentialised and inverted perceptions of Islam that reinforce each other.

What could be done to break this vicious cycle? Ahmed offers a very important suggestion: learning from Europe’s own past engagements with Muslim empires. He describes the rich historical encounters, noting the cross-pollination of ideas as well as the mutual acceptance of Christians and Muslims which existed throughout history.

One cannot help to wonder how this past can become relevant today? It would require a change in national narratives to teach the new generations about these moments of past civility or convivencia in order to foster new ones and transform the “alien” Muslim into a recognised member of the European community. It is a daunting task but can it be done?

Jocelyne Cesari is Professor of Religion and Politics, Director of Research at the University of Birmingham and a Senior Research Fellow at the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs at Georgetown University. Her most recent book is titled What Is Political Islam?.

Have something to add to the story? Share it in the comments below.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ