Supremacy of the Constitution

Constitutionalism should prevail over a person-specific or institution-specific approach

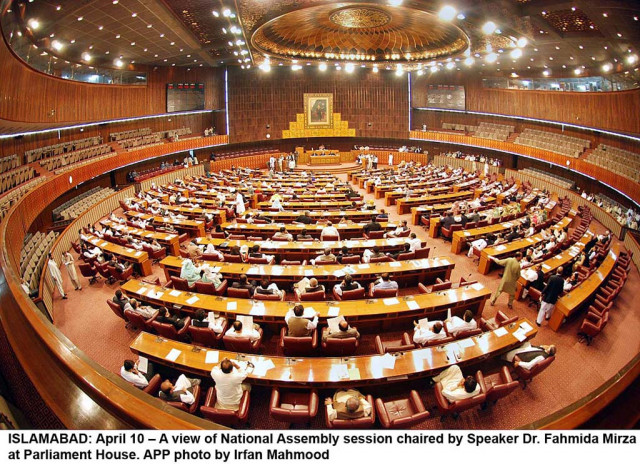

National Assembly. PHOTO: APP/FILE

Three specific court decisions, first, a Supreme Court decision regarding the period of Nawaz Sharif’s disqualification from contesting elections, second, a Supreme Court decision on changes to the electoral laws allowing Sharif to act as president of a political party and, third, an accountability court verdict regarding corruption cases against Nawaz and his family are likely to heighten institutional clash between the government and the judiciary. So, what is the role of each institution in the 1973 Constitution?

The legislative function involves the enactment of laws of both a constitutional and a sub-constitutional nature. Article 141 provides that “subject to the Constitution, parliament may make laws for the whole or any part of Pakistan”. Article 142 provides that “parliament shall have exclusive power to make laws with respect to any matter in the Federal Legislative List”. Article 238 provides that “subject to this part, the Constitution may be amended by [an] act of parliament”. Article 239 provides that a bill to amend the Constitution may be passed by the votes of not less than two-thirds of the total membership of each house of parliament.

The executive function relates to the enforcement of laws. Article 90 provides that ‘‘the executive authority of the federation shall be exercised in the name of the president by the federal government, consisting of the prime minister and the federal ministers, which shall act through the prime minister, who shall be the chief executive of the federation”. Article 97 provides that “the executive authority of the federation shall extend to the matters with respect to which parliament has the power to make laws”. In a parliamentary form of government like that of Pakistan, the executive participates actively, and often decisively, in the process of legislation. When the government has a working majority in the National Assembly, no new legislation can be enacted by parliament that is not approved by the federal government.

Part VII of the Constitution deals with the judicature. Article 184 provides that “the Supreme Court shall if it considers that a question of public importance with reference to the enforcement of any of the fundamental rights conferred by Chapter 1 of Part II is involved, have the power to make an order of the nature mentioned in the said article”. Article 189 provides that “any decision of the Supreme Court shall, to the extent it decides a question of law or is based upon or enunciates a principle of law, be binding on all other courts in Pakistan”. Article 190 provides that “all executive and judicial authorities throughout Pakistan shall act in aid of the Supreme Court”.

Even a brief reading of the above provisions reveals a separation and a balance of powers between the legislature (making law), the executive (enforcing law), and the judiciary (addressing disputes by interpreting the law). In light of this, I shall proceed to examine the current debate between parliament and the judiciary.

Parliament itself (more specifically, the government led by the PML-N) states that parliament is the supreme institution in the dichotomy of powers and has a final say in both constitutional amendments and ordinary legislation. Chief Justice Mian Saqib Nisar says that “judges cannot ask parliament to make a particular [ordinary] law, but they can examine it”. The chief justice observed that the authority of the Supreme Court has been defined in the Constitution and as such the court never transgressed from its authority because doing so would amount to violating the duty and oath that judges take under the Constitution.

An extract from the relevant judicial oath (Third Schedule of the Constitution) says “that, as judge of the Supreme Court of Pakistan … I will discharge my duties and perform my functions honestly, to the best of my ability and faithfully in accordance with the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the law”. I further reiterate Article 141 of the Constitution, which provides that, “subject to the Constitution, Parliament may make laws for the whole or any part of Pakistan”. Article 189 also provides “ Any decision of the Supreme Court shall, to the extent it decides a question of law or is based upon or enunciates a principle of law, be binding on all other courts in Pakistan”. In addition, Article 8 provides that, subject to the interpretation of the courts, laws inconsistent with or in derogation of fundamental rights shall be void.

In view of the above, I argue that the Constitution is higher than parliament, although parliament is empowered to amend the Constitution. No doubt, dialogue and debate within parliament strengthen democracy. There is also no cavil to the proposition that parliament has a constitutional authority to make laws or constitutional amendments. This authority, however, has to be exercised “subject to the Constitution” (Article 141). The Supreme Court, being the custodian of the fundamental rights of the people, is obliged to perform its duty in accordance with the Constitution — that is, to examine, interpret, and decide questions of law within the parameters of the Constitution.

The electoral law (the subject of the current debate) or any other piece of ordinary legislation remains subject to judicial review as per the dictum of the Constitution. At the same time, the Supreme Court should encourage public and parliamentary debate on matters of national importance, including efforts to reform the justice system. Parliament also needs to demonstrate its commitment to the substance of democracy through sustained high-quality dialogue on the constitutional role of institutions as well as issues of public importance, including health, education, poverty, and public accountability. Above all, constitutionalism should prevail over a person-specific or institution-specific approach in the supreme interest of the state and the people of Pakistan.

Published in The Express Tribune, February 25th, 2018.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ