When Junoon called for accountability, they meant it

Salman Ahmad, Ali Azmat and Samina Ahmad discuss ‘Ehtesab’ campaign, historic concert at Nishtar Park

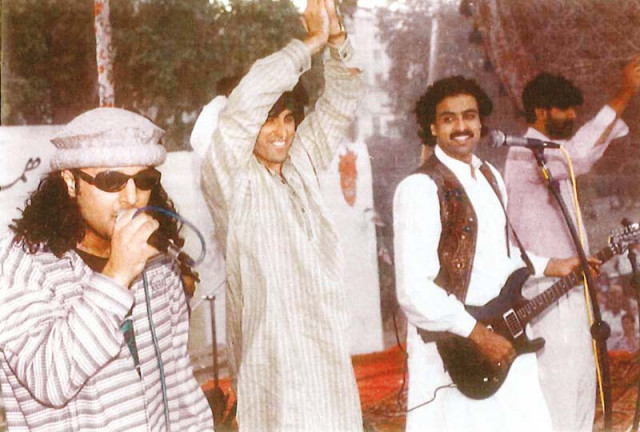

Junaid Jamshed also joined Junoon for the concert in Nishtar Park. PHOTOS COURTESY/SALMAN AHMED

“The authorities had refused to give us an NoC for the concert,” the Junoon front man tells The Express Tribune. Cowasjee, standing true to his reputation of helping anyone and everyone, got them their okay at the last minute.

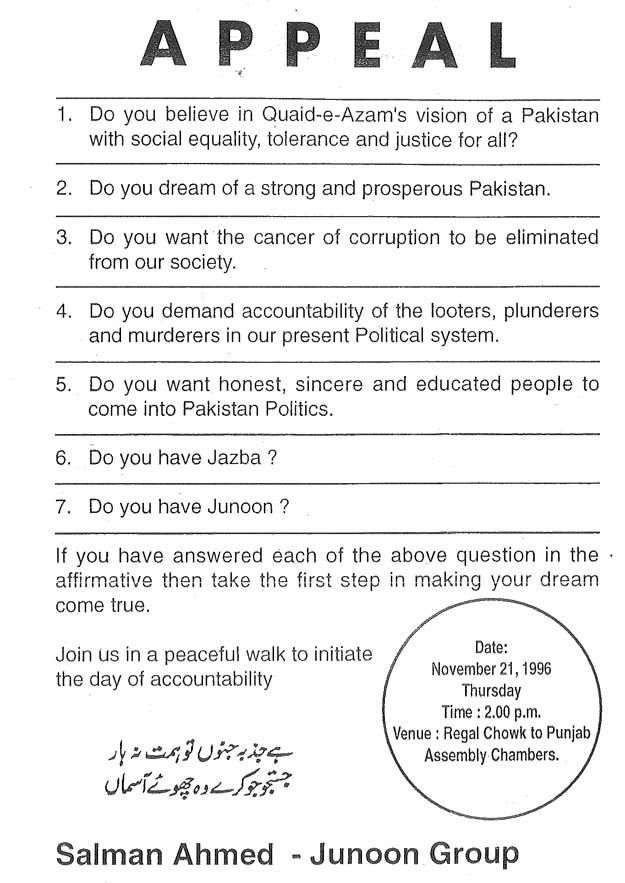

Riding high on the success of back-to-back hits, the country’s most exciting musical group had decided to take things a notch higher with a political campaign, calling for the answerability of the rulers.

1996 was a bittersweet year for Pakistan. Our greatest mind Dr Abdus Salam breathed his last. Punjabi cinema’s Sultan Rahi and Urdu ghazal’s Mohsin Naqvi were both gunned down. Junoon gave us some of our biggest hits, including our unofficial national anthem Jazba-e-Junoon, all put neatly together in an album called Inquilaab, and our cricket team failed to retain their world title during the last major international cricketing tournament played on Pakistani soil.

The mercurial Javed Miandad hung up his boots. Imran Khan, still buzzing with the 1992 triumph, formed Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf that would go on to turn ‘Ehtesab’ campaigns into a way of life. As you read these lines, Imran Khan is still at it. However, what’s worrying is the fact that some of the questions he is raising might be pertinent, yet somehow all this campaigning has today turned into a rather hopeless enterprise.

However, 1996 is remembered most importantly for Farooq Leghari who saw it fit to give the boot to the Benazir Bhutto-led Pakistan Peoples Party government. By that time, even if they were for a select few, chants of accountability had gained momentum.

Back when this 14-letter term had not become as big of a buzzword as it is now and popular music had not exactly crossed over into politics, Junoon was setting the wheels into motion.

While it may be tempting to claim that before Junoon’s arrival, music and politics had little to do with each other in Pakistan, it will be unfair to those who had long been writing against oppressive regimes and those who were putting the very lines to music. While its dividends can sure be debated one cannot take away from Junoon the fact that Pakistani music took a turn for the better, in part, because of them.

After holding demonstrations and walks against the “corrupt rulers” in different cities, in the initial stages of the ‘Ehtesab’ campaign, Salman began giving shape to a simple chord pattern he had in mind. For the lyrics, columnist Hassan Nisar and Salman’s long-time friend Shoaib Mansoor were approached. Drenched in his usual writing style, the lines that Nisar came up with were a bit too ambitious.

“His poetry advocated a bloody revolution if there was no accountability before the elections. It was very visceral,” Salman says.

Nonetheless, both Nisar and Mansoor’s lyrics were put to music at producer Nizar Lalani’s Tariq Road studio. “Ali Azmat, Najam Sheraz, Nizar Lalani, Shaheen Sher Ali and I sang on both the versions,” he adds. Unsurprisingly, it was Mansoor’s Ehtesab bus Ehtesab, Har sawal ka jawab that made the cut.

The ‘Ehtesab’ campaign was initiated long before the gig. Lahore saw artists like the Billo hit-maker Abrarul Haq and comedian Amanullah Khan take to the streets alongside Salman and his wife Samina. “My friend Junaid Jamshed had joined Junoon for the concert in Nishtar Park,” Salman recalls the December 21 concert.

He admits Nishtar Park was chosen simply because the band wasn’t being allowed to play at any other public place in the city at a time when ethnic violence was still simmering. Around 20 years have passed and the Junoon front man is still as sure as he was back then, of why the district administration failed to cooperate. “It was in the hands of corrupt politicians and they were all petrified of the slogan for ‘Ehtesab’.”

They had gotten a venue now but that did not end Junoon’s woes. The sound and light equipment required electricity that authorities had denied to them. “I went to a nearby mosque and asked the Imam to give us a power connection,” Salman says. It didn’t take the prayer leader long to recognise the band, after he was informed that they were the “Jazba-e-Junoon guys”.

“He said we could use the mosque’s generator,” Salman recalls. The permission came with only a small caveat. “The condition was to stop playing when the azaan starts.”

This was 1996. Junoon was on top of its game and there was hardly any other act that could match the charisma of these rock stars. Politicos were already on the wrong end of the stick; who wouldn’t want to witness the country’s biggest musical act take the country’s ‘biggest evil’ to the cleaners?

“Around 10,000 screaming Karachiites turned up for the show,” Salman claims, quickly adding with a smile, “They were young and foolish … like us.”

One cannot deny that the 52-year-old is still as enthusiastic as he was back when his band mates were by his side. “The entire crowd sang Ehtesab with us in one voice, saying, ‘We want accountability now!’” The band played a marathon of their biggest hits, back-to-back, for the next 90 minutes. “We wanted rule of law and were sick of corruption on all levels of Pakistani life,” Salman adds.

Visual representation

Once the campaign was over with, Salman approached Shoaib Mansoor again, this time to discuss a possible video for the song. While they had agreed to do the concert, Brian and Azmat did not fancy the idea of going a step ahead with a visual representation of the message the lyrics were meant to convey. It indeed risked a lot. In his book Rock & Roll Jihad: A Muslim Rock Star’s Revolution, Salman writes that even his “band had questions about my [political] intentions”.

It drew parallels between the lifestyle of the downtrodden and that of the affluent of the country, taking jibes at politicians and businessmen. According to BBC’s 1996 documentary Princess and the Playboy, the video takes a swipe at the royal treatment Asif Ali Zardari’s ponies received. “He [Mansoor] made a revolutionary video that scared the hell out of the government and PTV big bosses,” Salman says.

In a knee-jerk reaction, what has become something second nature to our leaders, the state slapped a ban on ‘Ehtesab’. According to a January 23, 1997, news report shared by Salman, the caretaker government of that time cited three reasons for the ban:

- It was detrimental to the election process

- It promoted the cause of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf

- It damaged national integrity

Having been blacked out by PTV, STN and radio stations, Junoon saw the print media siding with them. “They [the government] threatened us with dire consequences,” Salman begins once again. Stopping to quote a verse from Iqbal’s Shikwa, he continues, “We were banned, ridiculed and physically threatened but Junoon became an even bigger counter culture icon in the eyes of the public. That was the reason why I left a lucrative career as a doctor to go into music and the media, to inspire the youth and help bring about positive social change in Pakistan.”

Political backing

To the question of political backing for the show, Salman attempts to draw a larger circle. “Asking for accountability is the right of all Pakistanis and not of one person or a particular political party,” Salman says. Drawing parallels with the American Democratic National Convention 2016, he adds, “Artists like Lenny Kravitz, Katy Perry, Alicia Keys and Meryl Streep spoke for Hillary Clinton and against Donald Trump because that is what a democracy is about, power of the people, by the people, for the people.”

In a TV interview, Ali Azmat had mentioned that Jamaat-e-Islami was a driving force behind the concert. That does come as quite a surprise because this is the same party that was unhappy with PTV starting the show Music 89. Today, Ali does not recall any of that. “There was some religious party that helped us get the electricity connection. But I am not sure if it was Jamaat-e-Islami,” he says, quickly adding, “They too are, by the way, part of the problem. If they wanted to work for the betterment of the people, they could have.”

A family affair

There has hardly been a venture in which Samina has not had her husband’s back. Her memories of December 21, 1996, begin with a mention of Salman. “I had to sit on the stage throughout the Nishtar Park concert as Salman was worried about my safety,” she recalls, adding, “However, I don’t think I escaped from the brunt of it.”

As soon as she stepped inside the vehicle which was to escort the country’s most wanted rock stars out of the venue, she realised that a man from outside the window was tugging at the shawl around her neck. “All I remember is not being able to breathe … getting choked,” she adds. As Samina’s recollections proceed, one cannot help but think about the treatment of women at political gatherings of today, especially those held by Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf. Seems we haven’t changed much in the past 20 years.

Those who had surrounded the vehicle were pounding on its body with their fists for a reason best known to them. “I just let him have it and shut the window with all the strength I could gather … This particular scene still gives me the shivers. All credit goes to our skillful driver who managed to drive us out of there safe and sound.”

My activism is long dead: Ali Azmat

The Ali Azmat we now know is not the same. For starters, the hair is gone and with it has gone the no-holds-barred demeanour. Today, he likes to call himself Ali Azmat, the father, instead of Ali Azmat, the rock icon.

He recalls the Nishtar Park concert like a war veteran who has seen too many battles to remember a particular one. “Where is Nishtar Park? In Multan?” is his first response. When provided with a brief account of the gig, he takes a moment to catch his train of thought. “Frankly, I don’t remember much from that time.”

As the conversation proceeds, his begins to open up. “We had just one ‘hero’ [referring to Salman Ahmed]. He was everywhere. You see activism is one thing and pseudo-activism is another. Newsworthiness is okay but its constant pursuit becomes boring.”

But there’s a problem here. Azmat may have changed but isn’t he the same person who, until only a few years ago, was enjoying the company of the likes of Zaid Hamid?

“The world calls you crazy,” he reasons. For someone who seldom bothered about who said what, this is quite a change. “They say you are an artist, a darbari, a merasi. What do you have to do with serious business?”

As he begins to elaborate on what does not sound like a contradiction to him, Ali adds, “I have been seeing things happen for years. For someone like me, going to Channel V and winning an award would mean the world. But I went into depression after that.”

Glimpses of the old Ali begin to appear. “Once you become part of the system, you cannot step out of it.” Not long ago, he was on national television, defending the most absurd conspiracy theories that he had subscribed to. While that is no more the case, he still feels strongly about a lot of things. “This democracy is a sham. United Nations, Unesco, UNDP are all shams. They control the world. We have been crying hoarse for years. Nothing changed. Nothing is going to change. At the end of the day, we are all slaves to this hegemonic order,” he says.

Ali is quite clear when he says, “With the danger of sounding like a grandpa, I must say that I am past all that. My activism is dead.”

So what changed his fiery statements into a resigned shrug of the shoulders? “Marriage. My two daughters. They gave me a new view of the world. I recalibrated myself. I am in that stage of my life where all I worry about is them and nothing else,” he maintains.

Published in The Express Tribune, November 14th, 2016.

Like Life & Style on Facebook, follow @ETLifeandStyle on Twitter for the latest in fashion, gossip and entertainment.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ