Transition: From the book to the self

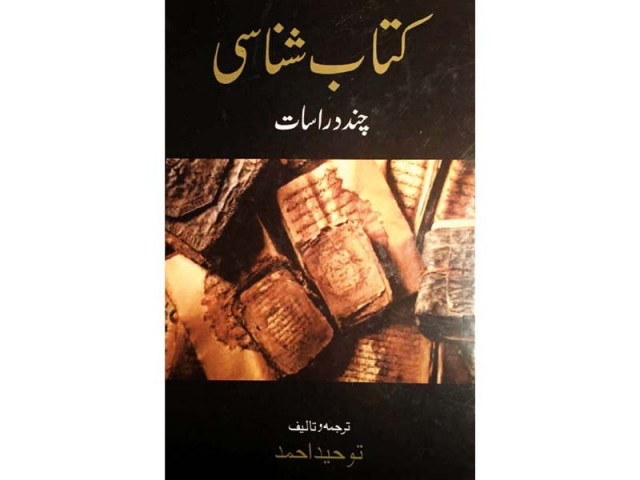

Former ambassador Tauheed Ahmed’s evocative collection of essays examines history of the written, printed word

Transition: From the book to the self

‘History of the Book’ or ‘The Book History’, as the discipline is known in Europe and the US, is not really a new perspective of intellectual inquiry. In Europe, it started as a modern academic discipline in 1958 with the publication of L’Apparition du Livre (Appearance of the Book), in which historians attempted to situate the ‘advent of the book’ within the modes of knowledge transmission through the material and cultural history of humanity.

One of the central questions of book historians, as they are known today, is to problematise and study the transmission of thoughts and ideas through the history of book publishing. According to a Harvard University Professor and Librarian Robert Darton, most of the book historians work in the time frame of post-Gutenberg Revolution, a field, which has expanded significantly within this disciplinary inquiry. However, the most fascinating intellectual probing is also part of this discipline, which extends its questions to the pre-Gutenberg era of unpublished manuscripts in the West. This particular aspect of this discipline not only expands our modern day understanding of the past, but also allows us to engage with it in a more meaningful way.

Kitab Shinasi includes eight essays, which deal with the ‘History of the Book and Publishing’ through various cultural contexts and scholarly point of views. Compiled and translated by Ahmed himself, the book is an evocative collection of essays, which expand on the topics such as the history of the discipline, especially in US and Europe, anthropology and book history, advent of printing press in India, the introduction of paper in Muslim societies, and many others. The book also contains an important essay by Annemarie Schimmel, Khataat, Dervaish aur Badshah, along with Moin-ud-Din Aqeel’s provocative essay on the beginning and evolution of printing in South Asia.

One of the most important essays is Shibli Nomani’s 1906 address to the annual meeting and educational exhibition of Darul Uloom Nadwatul Ulema, Lucknow. The essay opens with a nostalgic recollection of the indispensible relationship of Islamicate rule and the knowledge production of highest aesthetic import in India. Drawing attention to Muslim rule in India, spanning on about 600 years, Nomani laments the neglect and denial of all the treasure troves of knowledge, which still exist as part of the material and historical memory of the subcontinent. As he proceeds to mention the kind of books and manuscripts that were made part of the exhibition, one feels an enormous sense of guilt and ignorance about the gems that have constituted the Indian subcontinent’s multicultural and multilingual past; it not only makes one skeptic of what we now know as Western modernity but also of the originality of its concept whose traces are more vividly found in the politics and governance of Indo-Persian dynasties in Hindustan.

Among the six categories, which cover most rare books, ancient books, famous calligraphic specimens, handwritten manuscripts of famous authors and sultans and the series of art of communication, the exhibition also featured the royal proclamations that present hard evidence of groundbreaking political rule and justice system. For example, these proclamations, especially from the period of Mughal emperors Humayun and Shahjahan, make it very clear that there is hardly any mention of any derogatory terminology to address the Hindus or any discriminatory legal attitude towards them. Similarly, from emperor Alamgir’s period, the royal proclamation mentions the case of a Muslim occupying the property of a Hindu named Jungam in Banaras, which gets decreed in the court in the favour of the Hindu. The royal verdicts, which the Jangum family presented for this exhibition, portray a sympathetic attitude of the Alamgir court.

Another important aspect of the Islamicate rule in the subcontinent is the intellectual excellence and generosity of the royal court, especially for the people involved in the service of letters. Some of the proclamations in the exhibition brought this practice to light, which Persian poet Abu’l Qasim Ferdowsi (940-1020 CE) only proposed and dreamed of for the well being of an intellectual/artist: During the Mughal period, it used to be an important job of the designated court official (Parcha Navees) to report to the emperor about anybody throughout the country who was engaged in the service of letters or any other kind of art and intellectual activity. Recognising the importance of the peace of mind, the most essential component of the life of the mind, which mostly gets contaminated with worries of earning a livelihood, the Mughal court bestowed any piece of property or land generously to keep the intellectual worker unconcerned with the matters of material survival. This extraordinary system, which Firdowsi so vehemently desired for, was expanded from Bengal to Kashmir in exorbitant quantity. Nomani refers to an excerpt from Tuzk-e-Jehangiri, where the emperor mentions the record of these generous donations for the period of one year, in an unimaginable quantity.

Moreover, the art of archiving, in what is so mistakenly categorised as pre-modern India, is quite extraordinary in its record keeping and organisation. The record of every paper and deed was copied in multiple registers according to at least two calendars like the Islamic and Persian.

From the most rare books category, the most significant discoveries are Ibne Rushd’s manuscripts and translations, still unique to this region, including Aristotle’s Logic, which Rushd had translated into eight volumes. Along with other pertinent books, the exhibition also featured Rasail-e-Farabi and Rasail-e-Aflatoon, which could be consulted as shared intellectual heritage of humanity.

Clearly, ‘History of the Book’ is not only a fascinating academic discipline, but also one of the most ancient practices, which connect us to our long bygone ancestors. It enables us to go back to the wisdom that the dead bequeathed to us. However, its inception in Pakistan is yet to take place.

As Ahmed emphasises in his introduction to the book, universities in Pakistan have to be more proactive in facilitating such disciplines, which are not borrowed from the West, as is the case with most of our university programmes, and demand excellence that can only be achieved when engaged in original inquiries into our own intellectual history. In this context, it is useful to mention a 1973 agreement between Iran and Pakistan that led to the creation of Iran Pakistan Institute of Persian Studies in Islamabad, which has undertaken the task of collecting and publishing the rare manuscripts of the shared history of Indo-Persian cultures of the past millennium, thereby salvaging a rich part of South Asia’s intellectual history that might have otherwise been lost. As it happens, this institute’s efforts for preserving the intellectual gems of a bygone era still remain largely unknown.

On a different note, Kitab Shinasi, being an important contribution to the Urdu readership, could have been concerned with a more intellectually relevant preface. A preface, which is generally a backbone of a book, presents a contextual case and rationale of its existence while problematising the subject of the book through different perspectives. Unfortunately, as is the case with most Urdu books published in Pakistan, the preface is usually an ignored and poor expository practice. In any case, it is hoped that the revised editions of this book will address these issues and try to emphasise the academic significance of the Urdu translation of this important collection.

Introducing disciplines such as ‘History of the Book’ to Pakistani universities would help in channeling this untapped treasure of the Indian subcontinent’s own intellectual heritage, while at the same time sensitising a contemporary scholar to the need for documenting and spotlighting the heritage of our literary past whose reclamation would help in healing and broadening the calcified intellectual life today.

Title: Kitab Shinasi

Author: Tauheed Ahmed

Publisher: Fiction House

Price: Rs500

Pages: 260

The writer is a former AIPS junior fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and teaches literary studies at Kinnaird College, Lahore. She is currently translating and annotating Mirza Athar Baig’s novel ‘Ghulam Bagh’

Published in The Express Tribune, September 18th, 2016.

Like Life & Style on Facebook, follow @ETLifeandStyle on Twitter for the latest in fashion, gossip and entertainment.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ