My Elections World II

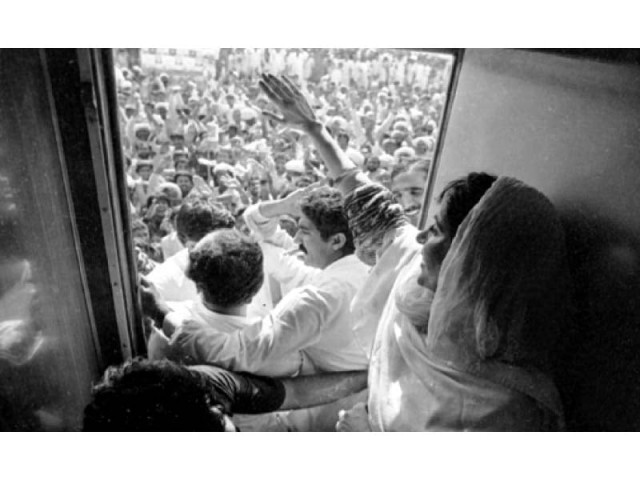

In 1988, rank and file of leftist groups were disappointed but mostly supported the PPP in Lahore

PHOTO: PPP ARCHIVES

The main ideological and political struggle, however, was between the IJT and left/liberal organisations. In Punjab University, National Students Organisation (NSO) had a strong presence, but the IJT was dominant. In Science College, in union elections a group of independent students contested elections against the IJT and won. I voted for the IJT. One of my classmates was from Khushab district. We soon developed a friendship with him. He introduced me to Professor Ali Abbas Jalapuri’s work. He first gave me his book Aam Fikree Mughaltay to read. Its language was too complicated for me to follow but what I understood of the content was enough to confuse me, and I began to question my ideas about role of religion in affairs of the state. I started reading newspapers and followed fierce ideological debates between the religious and secular thinkers of the time. The newspapers were full of stories about victimisation of political opponents by the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) government. Many PPP founder members had quit the party. Many senior opposition leaders, including the entire leadership of the National Awami Party (NAP), were in prison. During my school years like most people from my village I had believed that the NAP was working against the interests of Pakistan and that its leaders were paid Indian and Soviet agents. My ideas started to change while I lived in Lahore. In 1977 elections nine opposition parties formed an alliance named Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) and fielded joint candidates against the PPP. The election campaign was electric. I sympathised with the PNA. I was not sure whether I supported PNA because of my inclination to the left or my earlier religious roots. I was happy, however, that I did not need to make a choice between the religious and left/liberal parties. The election results were not in PNA’s favour and they accused the government of rigging. Newspapers reported many stories of rigging and PNA launched a protest movement that culminated in an army takeover. The army chief promised elections within three months. I was convinced that free and fair elections would be held in three months. However, a murder case was opened against Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. I regularly read the court proceedings in the newspaper and could see the partiality of the system.

I appeared in the FSc examination and did not do well. I did not have enough marks to secure a place in a medical college. The army had started their medical college and they would select students based on a test they gave. I was encouraged to appear in the entry test. I did not want to join the army but did not have the courage to tell anyone. I filled my paper with details of the reports of ZAB’s court case. The strategy worked. I was not called for the next step by the Army Medical College.

Finally, General Ziaul Haq decided to call elections but political parties were not allowed to take part. I was at Nishtar Medical College at that time and I had some friends whose family members were contesting the party-less elections. Many of them had contested elections before from platforms of various parties. I and many of my friends were strongly opposed to party-less elections. Later, when I met with any member of the assembly who had been elected in the party-less polls I was never able to respect them. Of course, my views had no impact on the business of the government. In 1986, I was posted in a rural health centre and wanted to move to Lahore to train as a psychiatrist. That could only happen with help from our member of National Assembly who was a federal minister and quite close to the Punjab chief minister. I happily accepted that help.

I was in Multan during the referendum under General Ziaul Haq. I went to a polling station with a friend. There was hardly anybody there. We were offered the opportunity to cast a vote. We had a discussion with the person representing the General’s camp. We tried to embarrass him for his lack of morals but failed utterly. He was adamant that ends justify the means in such a situation.

Elections in 1988 brought tremendous hope. The Movement for Restoration of Democracy (MRD) had been campaigning for party-based elections. Pakistan Peoples Party was the main force in the MRD, but other parties, too, had contributed. Especially the Left in Lahore had punched above its weight. There were discussions about joint candidates in the elections, but that did not materialise. Rank and file of leftist groups were disappointed but mostly supported the PPP in Lahore. There were rumours in leftist circles that army had given the PPP a list of people who could not be its candidates in the elections, and that the party leaders had accepted the condition. We had believed that the PPP would win an overwhelming majority. A colleague of mine would laugh at my enthusiasm. His brother was in the army, and he flew a helicopter which carried a brigadier on a mission to put together a coalition against the PPP. I watched the results with a group of friends in a room full of cigarette smoke. I remember our diverse reactions to the results. One of my friends believed the results had been rigged. I thought that the electorate’s opinion had shifted. For obvious reasons, my friend is a very well reputed political analyst.

There were four general elections between 1988 and 1997. Many families from our village who had settled in Lahore would go back home to vote. The candidates had their representatives campaigning in Lahore and buses full of voters left the city the night before the polling. The groups originating from the village competed in number of electors they could transport. It was an exiting activity.

Overtime I noticed another change. A family in the village next to us had always had a candidate either for the provincial assembly or National Assembly. They always won a majority in our village. They did not need to campaign. That changed with time. They came to need to go door to door to ask for votes and faced strong opposition.

The process has evolved over the decades I have observed. Some people who took victory for granted now face considerable opposition. New crops of politicians have joined the contest and power has shifted away from clans to smaller family units – maybe individuals.

Dr Muhammad Ayub is a psychiatrist and currently works as associate professor in Queen’s University, Kingston Canada. He is originally from Soon Valley, District Khushab

Published in The Express Tribune, July 10th, 2016.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ