Steeped in the anguish of finding oneself in unorthodox love and its incredible resonance across long bygone centuries, Verses of a Lowly Fakir brings to light a whole new meaning of love and surrender in the time of Coca Cola-sponsored Sufism.

The book offers a translation of the heart-wrenching Kafis of Shah Hussein, also known as Madho Lal Hussein. Shah Hussein, whose urs is still celebrated in Lahore as Mela Charaghan (The Festival of Light) was a 16th century Sufi, poet and weaver. Alam calls him a Fakir who wandered endlessly to chase truth in the “ephemeral playground” that he considered this world to be.

Originally born to a Rajput family from the Kalsrai clan, Hussein’s father converted to Islam during the time of Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526). Hussein was admitted at a madrassa for his earlier education. As Alam mentions in the introduction to the book, Hussein’s destiny as a wanderer was decided when his mentor, a teacher at the madrassa, Bahlol Dariai, who was himself a traveller, took him under his wings. He trained Hussein to not only memorise traditional texts but to find new perspectives of interpreting them.

The reader wonders if this was the breeding ground for his fierce intellect and passionate thinking, as Hannah Arendt calls it, which led him to be the most subversive of all the lovers and the most non-conformist of the intellectuals of his time.

Literature the soul of Pakistan, a source of guidance’

Hussein eventually became a malaamti. This is a state in which one is at the ultimate level of self-negation and seeks disgrace and censure against all kinds of social and egotistical elevation. He acquired a reputation despite his subversion to the puritanical values of the religious elite of his time.

Alam mentions a legend according to which Mughal Emperor Akbar, who had the capital temporarily shifted to Lahore was “unimpressed by the wine-to-non-alcoholic-drinks miracle performed by Hussein when he was brought before Akbar for interrogation, and sent him to prison. While Hussein was in the dock, his likeness showed up in the harem attended upon by the royal ladies. Mystified by the miraculous feat Akbar acknowledged Hussein’s credentials as [a] saint and set him free”.

As Alam puts it, the scholarship on Hussein seems to have a lot of gaps in sketching of his biographical details. However, strikingly so, Alam points out to a particularly ‘conspicuous gap’ in some of the most important books on the subject which do not mention anything about Hussein’s poetry:

“What’s conspicuously missing from all the above sources is any reference to Shah Hussein’s poetry. Mohammad Pir and Noor Ahmed Chishti are not concerned with Hussein, the poet or Hussein the self-claimed weaver, but remain fixated on Hussein, the saint. This is quite at contrast with how Hussein signs off at the end of almost every kafi: fakir nimana (lowly fakir)”.

Alam’s introduction is particularly important in understanding the bias regarding the historiography of Punjab’s mystics like Shah Hussein. Alam continues to elaborate the bias of historians like Pir and Chishti who remain ‘unabashedly partial to Islam’ and refuse to acknowledge the contextual details of Hussein-Madho Lal union. For instance Alam quotes Pir and Chishti’s acknowledgment of Madho Lal, who was Hussein’s young lover, and his conversion to Islam as the ‘salvation of the latter’, whereas refuse to pay attention to Hussein’s participation in the Hindu festival of Holi as the “spiritual syncretism of the lover and the beloved”.

Apart from a very devoted study of Hussein’s background and his socio-political surroundings, Alam expands on the key mystical concepts of passion, devotion, and most importantly, the inflamed feminine voice of the lover. As a translator, Alam is probably one of the few who not only gets to the music of the text but enters into what Gayatari Spivak calls the “protocols of the text and seeks the permission to commit the act of transgression that a translator earns from the trace of the other in the closest places of the self”.

A lover in various Punjabi mystical poems, perhaps starting from Shah Hussein who deliberately wrote in Punjabi, the language of the commoners when he could might as well have written in Persian which was then the lingua franca of the Mughal Empire in India, impersonate himself into a feminine voice and renders the heart breaking verses of longing and wahdat (union).

Alam’s translation of Hussein’s kafis is, what is without any doubt, an honest attempt at paying the homage to the Murshid (the master). This surrender, which is the starting point of any translation project, operates at two levels in Alam’s work. On one level, being a ‘disciple’ and poet himself Alam wants to bow down before Hussein and touch his feet as the ultimate expression for his devotion to the lover who sought love in the most unorthodox ways. On the other extreme, he submits to translation as the most intimate act of reading which ends up in the most powerful verses in the English language.

I recommend Alam’s translation for its nuances, which I hold very important as a translation studies scholar as well as from a pedagogical point of view. For instance, Alam has translated about 152 kafis for this volume and has differentiated the process of translation from the original read from the script and the original heard as a song by Pathanay Khan.

The protocols of a text expand when the source of the text is varied from its written original. Alam translates Kafi 72 from his reading of the original script as following:

I must go to Ranjha’s Village

Someone Please come Along

I beg, I plead, but I will have to go

All alone. The river’s deep,

The raft falling apart, wild animals

Occupy the landing. I’ll give my fingers’ precious rings if anyone

Brings news of my Friend

Nights are pain, agonizing days

Fresh the wound afflicted by the Friend

Ranjha, my lover known as a healer

My body suffers strange aches

Says Hussein, the humble Fakir

Sain sends the message.

However, Alam writes a variation of his earlier translation of the same kafi when heard from the legendary vocals of Pathanay Khan, a melody infused with the eros and emotion in Khan’s unique rendition that sometimes blurs the boundary of male and female for the listener and hence Alam’s varied translation:

They call me a stubborn child,

Pestering. I shall mewl for weeks

Till someone leads me to Ranjhra.

No one takes me seriously, I unfurl

My despair, throw myself at their feet.

I beg, I plead--- Better accept

I’ll have to make it all alone

Wretched me, what can I do?

Sain sends the messages…

Deep the waters, a beaten raft,

The wild ones prowl the banks.

Sain sends the messages.

Take my rings, take my bracelets,

Take anything I hold precious,bring

Some news of my Ranjhra…

Save your medicines, fellows,

Send for Ranjhra my ache,

My cure, my river, my raft.

As one can notice, there is a visible contrast between the two versions, in which the first one conveys the sense and the meaning whereas in the other, the translator dives into Khan’s musical translation of the written, which then enriches the varied version into the most emotionally charged verses of longing and dispossession.

Verses of a Lowly Fakir is an important book not only for the lovers of Hussein’s poetry but for students of literature and especially to the students of translation studies- a subject, which is still struggling to find its niche in Pakistan’s academic discourse. The translation pierces through the soul and even if not as much as the original Punjabi verses, it renders the pain and agony of a lover in the most emotionally intelligible and universal terms to a modern reader who may be unfamiliar with Punjabi. When infused with one’s shared suffering with the master himself the result is indeed Verses of a Lowly Fakir.

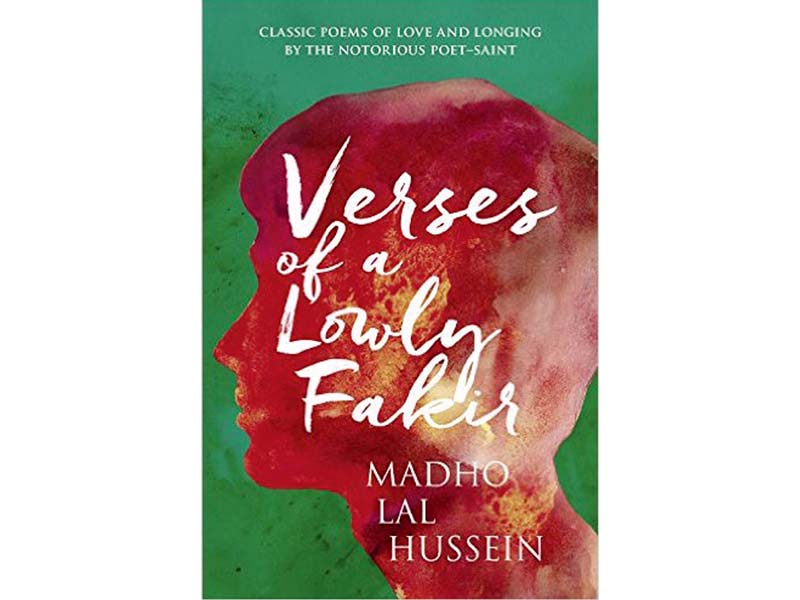

Title: Verses of a Lowly Fakir

Author: Naveed Alam

Publisher: Penguin India

Price: Rs800

The writer is the American Institute of Pakistan Studies fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and is currently translating Mirza Athar Baig’s short stories, ‘Be-Afsana’, in English

Published in The Express Tribune, May 15th, 2016.

Like Life & Style on Facebook, follow @ETLifeandStyle on Twitter for the latest in fashion, gossip and entertainment.

1732308855-0/17-Lede-(Image)1732308855-0-270x192.webp)

COMMENTS (1)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ