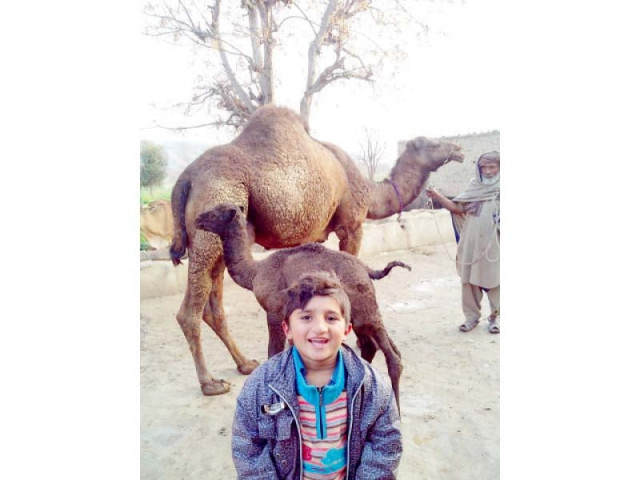

The Camel Country

Some of the camels from the villages were enlisted by the British era Camel Corps

Some of the friendships and connections among people historically

involved in the business outlived the profession.

Mirza Ghalib was proud of his forebears’ military profession. I can take only about five percent of the pride compared with the poet because some of my ancestors have been employed by military for one or two generations; initially British army but more recently Pakistan Army. The profession they mostly adopted, if it can be called that, for the known past was subsistent farming and keeping camel herds for transport. I grew up in a community where many households had camels and I can say I enjoyed the company of camels during my childhood. I lived in a hamlet of 14-16 houses where most of the families had descended from one couple. They considered themselves one big family. The language they used to describe themselves and address each other reflected that. There was freedom to walk into any house without hesitation. During my lifetime our household did not own any camel but I was able to pick a lot of information about the camels and culture of their keepers.

Three or four generations back before partition of India people from the villages in our area, Soon Valley, travelled to Ajmer and surrounding areas to buy camels. This journey of hundreds of miles was done on foot. Some of the people from that generation were around when I was growing up. They would narrate their adventures, probably with some exaggeration either deliberate or because with time their memories had become coloured by the richness of their wishes. One such story described a stay in a small village where the village head had gathered a crowd of locals to honour the visitors, provided delicious food and asked the visitors to sing songs in their own language and share their dancing traditions with the hosts. One person from our village known for his humour, we were told, made up a song full of profanity and sang it for the hosts.

Some of the camels from the villages were enlisted by the British era Camel Corps. The owners were allowed to stay home for part of the year but were prohibited to use those camels for transport of goods. Being part of the corps gave the camels and their owners a distinct status. Camels were regularly inspected by the officials. The owners would frequently violate the regulations about the use of camels for transport. My understanding is that the army used those camels mainly for transport of supplies in difficult terrains where motorised transport was not feasible. Some of those Camel Corps employees participated in tribal area British campaigns.

The camel-wallahs travelled long distances to transport goods. During early 20th century they would visit cities and towns to bring supplies for the village shops. For example, they regularly went to Shahpoor and Khushab from Soon Valley, a distance of nearly 50 miles. Their journeys took days and they took several breaks on the way where they allowed camels to graze unattended and cooked and ate in groups. They carried flour with them to bake roti. Their routines necessitated cooperation among group members. There was cooperation but also rivalries. Everyone identified with some group. These in- and out-of-group identities were not limited to these travels; they persisted in the village life as well.

The camel wallahs liked to sing while walking. Loud desert singing almost landed one travelling group in a big trouble. Around the time of partition there was a scare of a famine and a village shop owner went to fetch cereals to ward off its impact on the local population. When the train of camels was travelling back from Thal they came upon an area known for robbers’ ambushes. The shopkeeper requested the camel owners to keep quite as it was middle of the night and the sound carried a long way. They paid no heed to his request. A group of bandits was attracted but narrowly missed the camel train because of the dark.

The long-distance travelling declined with the construction of roads. However, many villages were still away from roads so the transport business continued till the eighties and even early nineties. When the army men who had fought the Second World War returned with their experience and exposure they encouraged their children to go to schools and gradually literacy improved. More and more people started joining Pakistan Army and some started frowning upon those who were still stuck with camels.

The transport business flourished once again in the seventies when economy got a boost from labour export to the Middle East. There was a boom in construction and camels were used to transport the material. The rates went up and by local standard the camel wallahs became rich. There was some seasonal work as well. Around the time of harvest the camels transported grain from farms. Usually the labour was paid in kind and camel owners got enough wheat to sustain the families for a whole year.

In the seventies, selling camels became another source of income. The local trade was boosted by Pushto-speaking buyers. They came at a certain time of the year. They were reluctant to disclose the place of their origin. They created a welcome competition in the market with their willingness to pay higher price for the camels. They had a unique way to quote the price. They would hold the seller’s hand and cover it with a piece of cloth and convey the amount of money on off with the movement of their fingers. Sometime these traders would stay for days as guest in the house while negotiating the prices. Their eating habits were interesting. They took a roti and divide it into equal pieces and each one took a piece. Once the roti was finished they’d pick the next roti.

The camel wallahs in neighbouring districts were part of a network. When travelling they were able to stay at one another’s house. They were served the food cooked in the house and got a bed to sleep.

In the nineties, the road networks extended to most of the villages and smaller hamlets. Gradually, tractors and trolleys took over all the transport business. The cash from trade of camels had already declined. Finally the number of camels in the villages declined.

Some of the friendships and connections among people historically involved in the business outlived the profession. Many elders from my clan saw themselves as part of that camel owner community till their death. When I worked in the area as a doctor and sometime even when I was posted in Lahore some members of the community approached me for help expecting that I’ll show regard for the old links.

Dr Muhammad Ayub is a psychiatrist and currently works as associate professor in Queen’s University, Kingston Canada. He is originally from Soon Valley, District Khushab

Published in The Express Tribune, April 10th, 2016.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ