Ibne Insha, Asad Amanat Ali and myth of the cursed ghazal

Why members of Patiala gharana continue to refrain from singing ‘Inshaji Utho’ 41 years after the poet's death

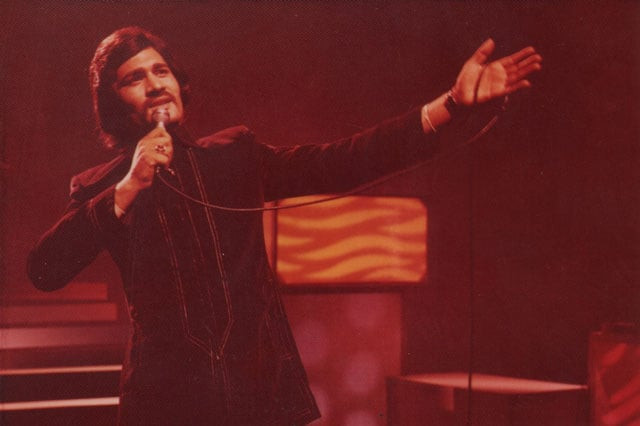

After his father’s untimely death, Asad led the Patiala gharana as its marquee performer. PHOTOS COURTESY: EMI PAKISTAN

Founded a generation earlier, the Patiala gharana identity was cemented perhaps by Amanat, its most significant scion. After his untimely death, it was his son Asad who led the family through the period of turmoil.

‘Politics hasn’t ruined India-Pakistan bond’

“Although I was quite young at that time, I remember when my father died, Asad bhai locked himself in his room for a good six months,” Shafqat tells The Express Tribune on Asad’s ninth death anniversary. He says the older son, knowing his responsibilities, honed his skills in the loneliness of his room and then emerged as the marquee performer of the gharana.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Nw6h2tq1VY

“We had this system where my father would turn in all his earnings to my grandmother who would then run the household. Asad bhai continued this. He held the family intact like a unit,” Shafqat recalls.

To him, the older brother was always the one who stood by him when he himself was going through a professional and personal transformation. “When you are part of a family and are through with your studies, you have this responsibility of reducing the burden from the sole breadwinner,” he says.

During his germination years, Shafqat spent his days in Karachi to try his luck in the industry. “He never asked me why I wasn’t contributing or what was I up to. I think that kind of support is very important.”

Shafqat credits Asad as a major innovator of Eastern music. “What we call fusion music today; Asad bhai started doing it in the 70s and 80s. He had released this album from London with Hamid chacha.

Artists throw weight behind Shafqat Amanat Ali

It was arranged in such a way that it had one classical piece, followed by a ghazal or a Punjabi folk song and then a popular number,” he says. “Asad bhai started singing arifana kalam and gave them a new spin. This Sufi wave that is so popular today, I would say Asad bhai is one of its pioneers.”

Demystifying Hindustani classical music for audiences was another of Asad’s remarkable achievements. “People tend to say that classical comes a little heavy on the ears. Asad bhai made it easy for them. He had this finesse about his performances ... this rakh rakhao.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4-mbAFJQ138&nohtml5=False

Despite being very classical and traditional, he would give a contemporary touch to everything. Basically what was started by my father and Fateh chacha, Asad bhai and Hamid chacha took that to the next level.”

Shafqat borrowed from Asad the art of keeping audiences involved during performances. “Asad bhai knew how to keep them engaged.” Shafqat says all three of Amanat’s sons are sopranos. “So we have this ability to sing at a very high pitch. Normally when you reach out for the high notes, your voice gets shrill. From him I learnt the ability to control that and maintain certain roundness to the voice,” he maintains.

Asad’s death and the subsequent vacuum in the family brings Inshaji Utho back into the conversation. Shafqat reluctantly debunks the myth, but his version is justified. “It was my father’s last ghazal.

When he died, everyone started associating it with the death,” he says, adding, “And then Ibne Insha himself died. My eldest brother Amjad bhai also used to sing it. He died. I don’t recall the producer’s name but he too died. And then Asad bhai.”

He pauses for a brief moment. Shafqat says no one in the family, including him, is superstitious. “Life and death are in God’s hands. We have no control over it. It’s just the painful memories that this ghazal brings back for us,” he says. He admits that there’s an “emotional ban” that has been placed on him.

“My phuppos and sisters are concerned. They want me to refrain from singing it,” he says. When reasoned with counter arguments, he submits, explaining, “I know ... You see. Facts don’t matter for the family. They just want the guy to live.”

‘My brother’s song’

Shafqat’s uncle, Amanat’s understudy and Asad’s stage partner Hamid Ali Khan feels people do think differently within the family.

“I am compelled to sing it [the ghazal] whenever I am requested to do so,” he says, adding, “It belongs to my brother. I have to sing it.” Hamid says it is the succession of deaths that made family members think this way.

“It is also the poetry that is like that. Obviously it’s not like whoever sings it, will die,” he adds. When asked if there is a pact within the family members not to sing it and whether his own sons sing it, he says, “Everyone sings it. There’s nothing more to it.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DddxcQkmUxw

Ibne Insha and Hodgkin’s disease

Over three decades ago, Dr Riaz Ahmed Riaz wrote his doctoral dissertation on Ibne Insha at University of Punjab. Author of numerous titles on the late poet, including Ibne Insha: Ehwal-o-Asaar, Riaz feels the ghazal is indeed cursed.

“Inshaji was 48 or 49 when he contracted Hodgkin’s disease about which he had jokingly written that Thomas Hodgkin discovered the disease but not its cure,” he says, adding, “When Inshaji realised that his days are numbered he wrote nazms like Ab Umr Ki Naqdi Khatam Hui. This ghazal was also composed during the same period.”

Riaz says in his letters to Sarfaraz Iqbal and Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi, Ibne Insha wrote that this “ghazal’s curse has caused my decline”. He however disagrees with the fact that Amanat and Asad’s deaths have to do with this curse. “Yes they did sing it but it was more about their own respective health issues,” he adds.

Death is inevitable

Amjad Islam Amjad is one of the few surviving giants of the post-Partition wave of writers. To him the myth is meaningless. “These things spread confusion and nothing else,” he holds. “Tell me one thing, is there any ghazal in this world whose composer, poet and writer did not die?” he with a laugh questions.

Amjad says he has never read or heard about Inshaji himself writing that the ghazal is cursed. “Yes I know that some people say that it first killed Inshaji and then Amanat and then Khalil Ahmed [the producer],” he maintains.

The playwright feels it is the general tenor of the ghazal that gave rise to the myth. “It’s just because it talks about death … people here have nothing better to do than cook up such stories.”

Critic Sahar Ansari concurs with Amjad. “Yes, I think because it has words like kooch (to decamp) in it hence people associated this story with it,” he says. “Inshaji had written it long before Amanat Ali sang it. It was part of Chand Nagar,” he maintains.

When Amanat popularised it, he recollects, people thought it was the work of 19th century poet Insha Allah Khan Insha. “Inshaji used to write a column for Akhbar-e-Jehan. He had to clarify that it was his ghazal.” Quoting Faiz, as he so fondly does, Sahar says, “Jin ka deen pairvi-e-kizb-o-riya hai un ko, Himmat-e-kufr mile, jurrat-e-tahqiq mile (May there be given to deceit’s slavish votaries, Will to deny and to seek—),” and continues, “It is this jurrat-e-tahqiq that is lacking in us. People don’t want to investigate. They just listen to these pointless tales and spread them.”

Authorial intent

Praising The Waste Land, critic IA Richards had once hailed Eliot for expressing the disillusionment of a generation, to which the modernist poet responded by saying that it wasn’t his intended meaning. Eliot had quashed the analysis by terming it nonsense!

While Ibne Insha is no more to explain what he really meant by the ghazal but he did talk about the issue in an interview with Ibrahim Jalees for Radio Pakistan. “Asad has sung it really well. I give him credit also because I had written it with a very different feeling,” Ibne Insha had said.

Skilfully skirting Ibrahim’s question about the feeling, he added, “You shouldn’t ask me that, nor will I ever tell you. Some people think there’s a political connotation to the ghazal. That, I can tell you, is not true.”

Inshaji said that he had written it in another country. “Amanat enhanced that emotion in it and his son did it even better,” he had said.

Translation of Faiz is by Victor G Kiernan

Published in The Express Tribune, April 8th, 2016.

Like Life & Style on Facebook, follow @ETLifeandStyle on Twitter for the latest in fashion, gossip and entertainment.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ