Political musings: Taj Haider on Karachi’s descent into chaos

Says Ayub Khan played the ethnic card for the first time in the metropolitan city

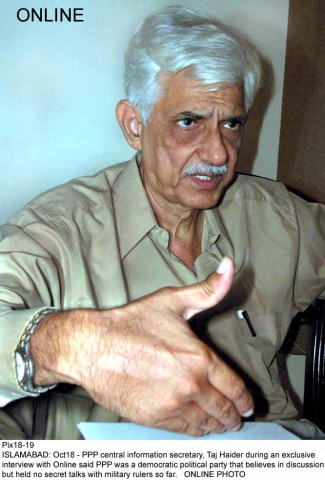

Senator Taj Haider. PHOTO: ONLINE

Historians trace Karachi’s bourgeois life to 1729, with the construction of a walled city by Hindu merchants. The walled city had two gates, one facing the sea called the Kharadar (salt) gate and the other facing the Lyari River called the Mithadar (sweet) gate.

Although these gates were demolished during the British Raj, the neighbourhoods bearing these names still exist. When the Talpurs conquered the city in 1794, followed by the British conquest of Sindh in 1843, the city began to develop along modern lines.

By the 1850s, Karachi’s outlook was replete with administration offices, shipping companies, banks, businesses and warehouses, and small industry units on its outskirts. The city was built specifically for trading purposes and as a gateway for trade with Central Asia. Much before Independence, the city had modern community halls, libraries, drama clubs, gymkhana, bars, billiard rooms and several tea houses.

A Sindhi writer, Pir Muhammad Rashdi, described the Karachi of the 1930s as “a hub of intellectuals and sophisticated European style shops and markets”. The city owes its development to Hindu, Goan, Parsee and Muslim businessmen.

After Independence, some 600,000 Muslims, who had migrated from India, settled in Karachi. The city was declared the capital of Pakistan. With the influx of new settlers, the population of Karachi swelled by 400%. It became the home of bureaucrats, writers, artists, politicians and diplomats. In the following years, the city absorbed hundreds and thousands of more people coming in from all parts of the country to earn a living.

Karachi retained a reputation for its libraries, cinemas, bars, bookshops and educational institutes for another two decades before it started degenerating into a city of guns, drugs, crime and mafias. There are several reasons for this transformation from an elegant city to a chaotic mega-urban centre. Experts of urban planning blame unchecked migration, lack of infrastructure planning, rampant encroachment and corruption.

This article, however, aims to explore a different aspect: how students of political science view this transformation.

In an exclusive interview with The Express Tribune, prominent resident of the city and renowned politician, Senator Taj Haider, talks about ethnic divisions and their impact on Karachi’s politics.

According the senator, roots of the chaotic law and order situation and ethnic strife dates back to the early 60s. He narrates an event from January 1965, when Gohar Ayub, the son of military ruler Field Marshal Ayub Khan, led a procession to celebrate the victory of his father in the presidential elections against Mohatarma Fatima Jinnah.

"He (Ayub Khan) played the ethnic card for the first time in Karachi. Gohar Ayub organised the victory procession. He used the Pakhtun card. Gohar Ayub led the procession passing from Lalukhet area with the display of weapons. They resorted to aerial firing to spread fear. I think it was the third or fourth of January, 1965. This marked the introduction of gun culture in Karachi. Before that, people of the city did not recognize the sound of gunfire."

And thus, for the first time, ethnic tension as a result of the Pakhtun and anti-Pakhtun friction created a fault line that has been hard to bridge ever since.

Change in trade union laws

In the 60s, trade unions in Karachi were very strong. They played an important role in the events that led to the downfall of Ayub Khan. After General Yahya came to power, he changed the trade union laws through a presidential decree. He allowed the formation of more than one trade union in an organisation. Hence, the trade unions also got divided along ethnic lines. The same happened with the city’s student unions.

The 1972 language riots

In the early1970s, the city witnessed riots on the language issue. These happened when Senator Haider’s party, the Pakistan Peoples Party, was in power.

The riots were caused by the passage of a language bill by the Sindh Assembly, declaring Sindhi to be the provincial language along with Urdu. In hindsight, Haider admits his party had failed to deal with the issue prudently.

"Instead of giving logic, some nationalist elements in our party said it was our right. This alienated the Urdu-speaking community further. It is in my knowledge that the OB van of PTV remained parked outside the chief minister’s office. [Zulfikar] Bhutto kept asking Mumtaz Bhutto (the chief minister at the time) to make a television address, but he kept delaying it. The matter was defused a little when Zulfikar Ali Bhutto came on radio and Mumtaz came on TV later on. But the damage had been done," says Haider.

Emergence of Altaf Hussain and the APMSO

The ethnic grouping had begun to penetrate into student unions. And among these student unions, the most notable was the emergence of the All Pakistan Mohajir Students Organistion (APMSO) by a group of Urdu-speaking students of Karachi University (KU). From APMSO later emerged the MQM.

Senator Haider recalls the emergence of Altaf Hussain. "Altaf Hussain was not being given admission in the university. He then held a hunger strike. My sister was in the academic council and she pleaded his case. She said if a person wants an education, he should be accommodated. I think this was sometime in 1977-78. His name had already come in opposition due to the hunger strike he orchestrated to get enrolled. Thus, he was among the co-founders, and became the leader, of APMSO."

Bushra Zaidi incident

Haider narrates another incident where a college-going girl from an Urdu-speaking family, Bushra Zaidi, fell down from a crowded minibus and died. "This was a very important incident although it was purely an accident. She was Urdu speaking. The public transport was mostly in the hands of the Pukhtuns, from the owners to drivers to conductors. She was travelling like most students, hanging on to the bus. She lost her grip, fell down and died. I think she was from Sir Syed College. This was around 1985-86. They (the establishment) immediately gave it the ethnic touch."

The incident was followed by a wave of riots across the city. Organised attacks were carried out at Aligarh College, shares Haider, maintaining those were all pre-planned. Announcements were made from mosques and the riots continued for three days. The government, on the other hand, did not try to stop the bloodshed, he claims.

"Many Biharis (who had migrated after 1971) were settled in Orangi. Among the newly-settled community were some elements that were trained militants. On the other side were Pakhtun militant elements. The establishment was behind these riots. Sane voices from both communities tried to diffuse the tension. People like Akhtar Hammed Chacha, who had started the Orangi Pilot Project, tried his best to rehabilitate the Bihari community. But the militant elements working under the patronage of the establishment continued fueling the fire … The city witnessed its worst bloodshed. And then we found the emergence of the MQM at Nishtar Park."

Playing the ethnic and religious card

The ethnic and religious card has always been used to suppress democratic and progressive movements. It is the easiest way to divide people. Once an environment of fear is created in the society, its respectable members who preach co-existence and unity meld into the background and militant elements come to the forefront.

"If we know that our locality is about to be attacked tonight, the immediate issue that arises is: who will protect us?” explains Haider. "In such situations, hooligans and militant elements, that generally constitute a minute portion of society, take the lead. They start dictating to the society. The same happened in our case."

The senator says the religious card was used against progressive movements thereon. Pakistani society was divided along religious lines, especially during Ziaul Haiq’s era. However, Zia’s religious card did not work in Sindh; there, he used the ethnic card, says Haider.

"PPP swept the local bodies election in 1983 in Karachi and the same happened in the 1985 general elections. Ziaul Haq had organised non-party based elections. In Sindh, the masses rejected candidates who had affiliations with religious parties: anyone who claimed to have some affiliation with the PPP won."

According to the senator, once Zia realized that his religious card was not working in Sindh, especially in Karachi, he created a new team – a team that could play the ethnic card. "You can do social work on ethnic lines, but not politics. Politics is always secular," stresses Haider. "Our constitution is very clear about it. Under Article 36, it is the responsibility of the state to end all prejudices in the society in whatever form it may be. But unfortunately, a state within a state has always used the same prejudices, with militancy flourishing under its guise."

Published in The Express Tribune, February 29th, 2016.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ