Faiz on the doorsill of Anis, Dabeer

Revolutionary poet’s incomplete marsiya is a monument of cultural and historical significance

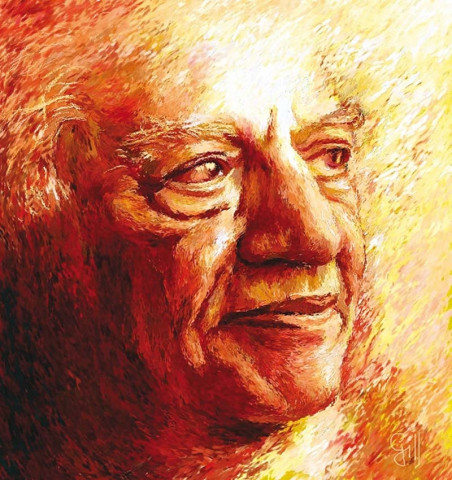

Faiz notes that marsiya is a genre that moved away from the rich and went back to the poor. PHOTO: FILE

Marsiya holds a special place in Urdu literature. A genre that standardised elegiac poetry, its distinction lies both with its proponents and historical significance. It has served as an instrument of recording history and a milieu of language and human values. One could say that never once did marsiya knock doors of the powerful; it never eulogised the courts, rulers and conquerors and rather, in poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s words, is “consequential because it moved away from the rich and turned to the poor”.

Few know that Faiz himself participated in this historical continuity and penned a marsiya, titled Raat Ai Hai Shabbir Pe Yalghar-e-Bala Hai. Comprising 12 bandh (six-line verses), this incomplete marsiya was published for the first time in the 1975 Muharram edition of Akhbar-e-Jahan. When Faiz’s magnum opus, Shaam-e-Sheher-e-Yaraan, came out in August 1978, it was part of the collection under the farmaishi (by request) section.

‘What was the communist threat to Pakistan?’

In critic Fateh Muhammad Malik’s words, “It is true that a sufi is a real comrade. The way of Imam Hussain (RA) is the way of the real sufi. This idea was always part of Faiz’s creative conscience.”

Among other things, one attribute that makes Faiz’s body of work unparalleled is his connection with the classics; almost as if he strings together the past and the present. The marsiya tradition itself is very classical at its core and in tracing Faiz’s footsteps on the doorsill of giants such as Mir Anis and Mirza Dabeer, we shed light on another aspect of the creative conscience of this man called Faiz.

By no means are we trying to extrapolate any conclusions from investigating this particular creative pursuit of Faiz in a way that it satisfies our reductionist understanding of the literary giant; it is more of an attempt to unravel another aspect of Faiz’s genius.

If writer and critic Ali Sardar Jafri is to be believed, one cannot call it a marsiya. “It will be incorrect to call it a marsiya. It does not comprise the specifications of the marsiya, however, it does embody Faiz’s typical style. By virtue of meaning, it can be termed a marsiya,” he writes.

Jamiluddin Aali — a man in search of identity

Interestingly, Professor Dr Abul Khair Kashfi, in a rather surprising fashion, laments how Karbala could never become a symbol for Faiz. Without directly naming the poet, he writes, “A big poet of Urdu with whose faiz [literal meaning of the name] Urdu literature was popularised in many countries, included a farmaishi kalam section in a collection [of poetry] of his. In it, there is also a marsiya. This means that the marsiya is not part of Faiz’s personality or craft. The poet who penned Africa’s grief and wrote for the suffering of Iranian students, Karbala could not become a symbol for him,” is his observation.

At this point we’re digressing but the anecdote signifies two sides of the debate, highlighted by scholars such as Mushfiq Khawaja and Prof Muhammad Raza Kazmi. While discussing Frost’s famous poem Fire and Ice, famous cricket commentator Chishty Mujahid once told his daughter, “Had I written the same lines, you’d brush them off. But since this is Frost, you consider them a work of art.”

Khawaja dismisses the debate in one simple stroke, saying, “As far as the importance of this marsiya goes, it is there only because it has been written by a literary giant of this day and age.” Kazmi refuses to look at the marsiya in isolation. He pivots his argument on Faiz’s contribution alone. “Faiz is one of those poets who have given modern nazm a voice of its own hence we cannot ignore the significance of this marsiya by taking it for granted.”

As to why Faiz wrote the marsiya, there’s more speculation. In 1982, marsiya writer Waheedul Hasan Hashmi wrote that Faiz used to live in Model Town, Lahore. His Shi’i friends suggested that like him, Josh Malihabadi is also a communist and he writes marsiya. If Faiz too writes one, the genre will also have his name in it.

Scholar Dr Hilal Naqvi finds little weight in this assertion. He states when Faiz wrote the marsiya, he was living in Karachi. During a February 1978 APWA College mushaira, Naqvi had asked the question from the man himself. Faiz had responded by saying that “some people in Karachi had requested” him to do so.

In a February 18, 1983 interview of Faiz, Ashfaq Ahmed revisited the question. “I don’t believe that you wrote this marsiya over a request,” he stated. “By request I meant the ongoing struggle of that time … Karbala is part of our collective consciousness,” Faiz had replied. A subsequent interview saw Faiz give a more comprehensive answer. “Firstly, the subject is such that I connect with it. Even otherwise, my teacher ZA Bukhari also used to write marsiya. I too was requested, and so did I write. Karachi’s milieu also played its part.”

Advocate Munawer Abbas belonged to Malihabadi and Allama Rasheed Turabi’s close circle of friends. He maintains Faiz had honoured Turabi’s request, which was made when the former had paid the latter a visit.

In Naqvi’s words, from whose research we have benefitted immensely, incomplete it may be, the marsiya stands as a monument of cultural and historical significance. One can certainly not become an Iqbal or Faiz by skirting this intellectual continuity.

Published in The Express Tribune, February 22nd, 2016.

Like Life & Style on Facebook, follow @ETLifeandStyle on Twitter for the latest in fashion, gossip and entertainment.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ