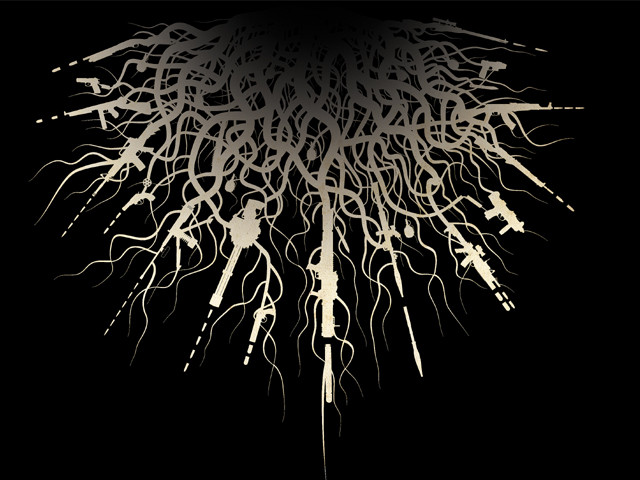

Radical roots blow back

The ideological bond between jihadis and Pakistani security forces is anything but broken...

As a teenage jihadi training at al Qaeda’s infamous Yawar Camp in Khost in the early 90s, Ali Sher once met Osama bin Laden and Jalaluddin Haqqani on what he describes as the luckiest morning of his life. The 35-year-old father of a baby boy is overwhelmed with emotions when he remembers this time.

His last assignment was to hide Mullah Akhtar Usmani, the Taliban commander of Kandahar, in Pakistan, after the Twin Towers were bombed and before the Taliban regime was driven out by the Americans.

“What I liked most about jihad,” he says, “was that we were backed by the ISI [Inter Services Intelligence].”

Though he quit the complicated jihadi underworld soon after 9/11, Ali still remembers the ISI officers he worked with. Today, he finds it hard to accept that the intelligence apparatus that was once hand in glove with jihadi groups is now out to get them.

“I do not believe that the ideological relationship between us and the ISI was so weak that it was broken by 9/11,” says Ali,

recalling how jihadi ideologues like the slain Maulana Yousaf Ludhianvi of Karachi’s Binori Town seminary were revered in the army.

His conviction seems to be based on sound reasons; the ideological bond between jihadis and Pakistani security forces is anything but broken. The Punjab governor’s assassination in the federal capital a few weeks ago was just the latest manifestation of radicalised ideologies infiltrating Pakistani security forces. When an elite police commando shouted “Allah-o-Akbar!” after spraying Punjab Governor Salmaan Taseer with bullets, it was a grim reminder of how radicalisation has seeped into Pakistani security forces.

Taseer’s assassination has raised a fundamental question: how genuine are concerns that segments of Pakistani security apparatus are inclined to the hardline ideology espoused by al-Qaeda?

Though Malik Mumtaz Qadri’s crime was immediately dubbed ‘an individual act’ by commentators and politicians, it is reflective of much more than that.

“Security forces are made of and influenced by society. They are not raised in isolation, so their radicalisation is natural,” says Fida Khan, who has been covering Talibanisation in Pakistani society for a Japanese newspaper. “What was officially begun during Zia’s era is now haunting security institutions,” he adds, referring to the deliberate state policy between 1979 and 1988 in which radicalisation was promoted in the army.

Taseer, an outspoken liberal, was at the heart of a controversy surrounding a Christian woman charged with blasphemy. Aasia Bibi was sentenced to death by a local court in central Punjab for allegedly insulting Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), despite the fact that it is common knowledge that the blasphemy law is used to settle personal vendettas. The woman and her family denied the charge, and it was Taseer who visited Aasia Bibi in prison and called for an amendment to the unfair law. But on Friday, December 31, 2010 clerics burned Taseer’s effigies when they carried out countrywide protests against the government’s alleged plan to repeal or amend the blasphemy laws. This, despite the fact that the government has categorically denied having any intention to amend the blasphemy laws several times.

Taseer’s murder appears to be unique because the governor was a high-profile target. It seems that this is the first time that an elite police guard has been persuaded by a radical ideology to kill a person he was deployed to safeguard. But in recent years, there have been several incidents in which low-level officials from Pakistan’s military and paramilitary forces have become radicalised enough to actually defect to al-Qaeda and the Taliban.

A few years ago a Pakistan Army officer from Chakwal abandoned his training at an infantry college to join a Taliban faction led by Commander Abdul Wali alias Omar Khalid in Mohmand. This young radical threatened to blow up a military academy for fresh recruits in Abbottabad though he thankfully never delivered on his threat. Similar reports of young army officers abandoning their posts to become Taliban foot soldiers in the tribal badlands are becoming more common than ever. The military regularly denies these allegations but, in 2008, British journalist Christina Lamb revealed that a Taliban fighter killed by Nato’s Special Forces in the Helmand province of Afghanistan was identified as a Pakistani army officer. This claim too was denied by the Pakistan army.

Similarly, in the 2009 attack on the Pakistani Army Headquarters in Rawalpindi, the nine militants were led by Aqeel alias Dr Usman who was once associated with the military. The radicalisation of security forces was also apparent when a suicide bomber who attacked the office of World Food Programme in Islamabad turned out to be a member of the paramilitary Frontier Constabulary.

Should such incidents be taken as individual acts or do they reflect a problem much bigger than a single person getting carried away by religious ideologies in the heat of the moment? While it may be comforting to believe the ‘lone gunman’ theory, the frequency of these acts indicates the presence of a larger and far more dangerous trend.

“You need to understand the whole dynamics under which security forces and especially the secret services operate. Religion comes into the picture as a motivational tool right at the outset of training, but there are chances that it can become the dominant ideology, even eclipsing the working command and control structure,” says Irfan Shahzad, an Islamabad-based expert who has been tracing the trend of rising militancy in Pakistani society and the country’s armed forces.

But a snippet from Ali Sher’s conversation is enough to understand the phenomenon: “the ideological bond between them [the ISI] and us was simply unbreakable… that made us bolder and we were certain that no one on earth could defeat us.”

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, January 16th, 2011.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ