Is your school just a bank in disguise?

Imagine a typical classroom: Rows of students sit at desks that are arranged with surgical precision, designed to prevent any interaction.

Half the class is zoned out, nodding occasionally, but mostly counting down the minutes until the lecture finally ends. The teacher who stands at the front of the classroom delivers the same lesson day after day, decade after decade, stuck in a never-ending loop with no feedback. Fluorescent lights flicker overhead, never quite giving off enough light.

The teacher lectures, the students take notes. Facts are memorized then regurgitated with apathy.

Paulo Freire would say this scene perfectly depicts what he calls “the banking model of education”, a traditional method of teaching that has shaped our classrooms for generations.

In this model of education students are treated as empty “bank” accounts into which knowledge is deposited by an all-knowing authority figure.

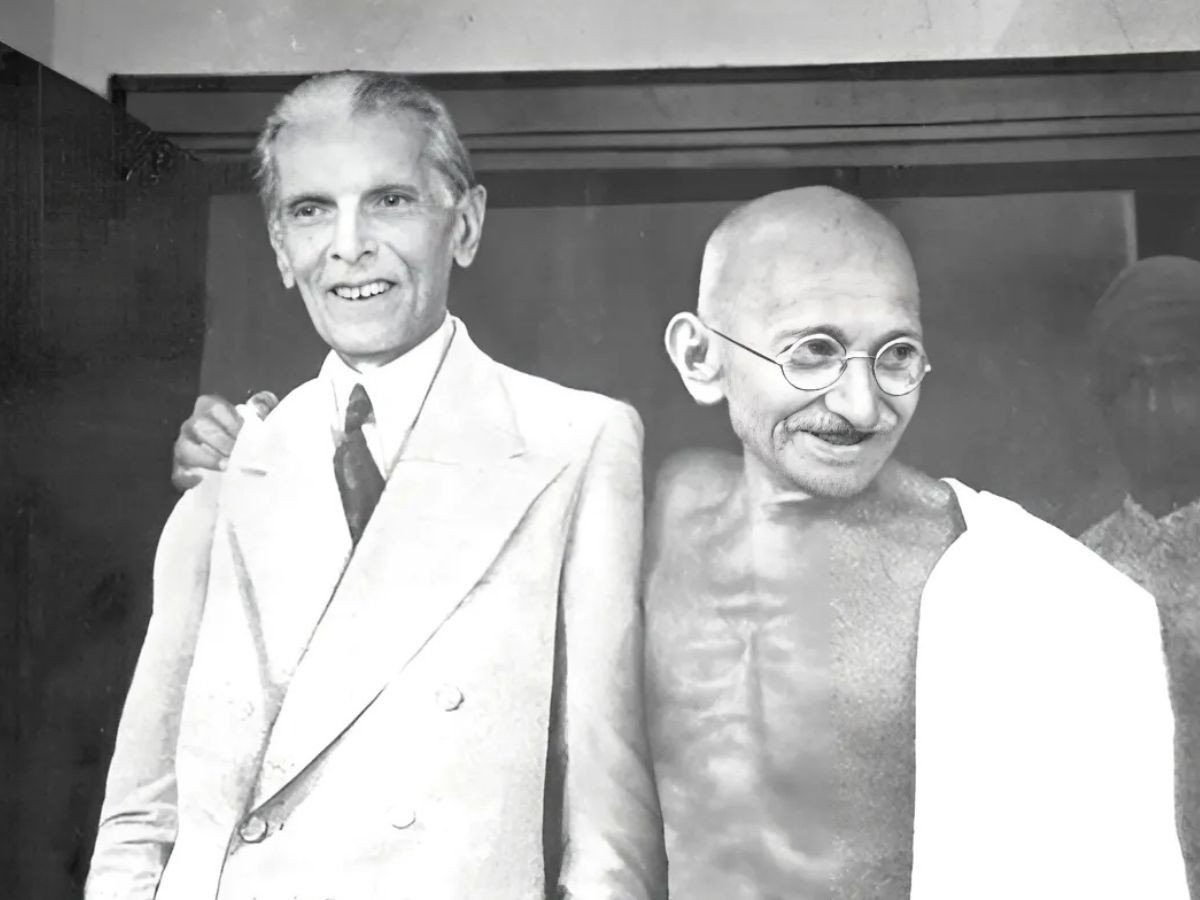

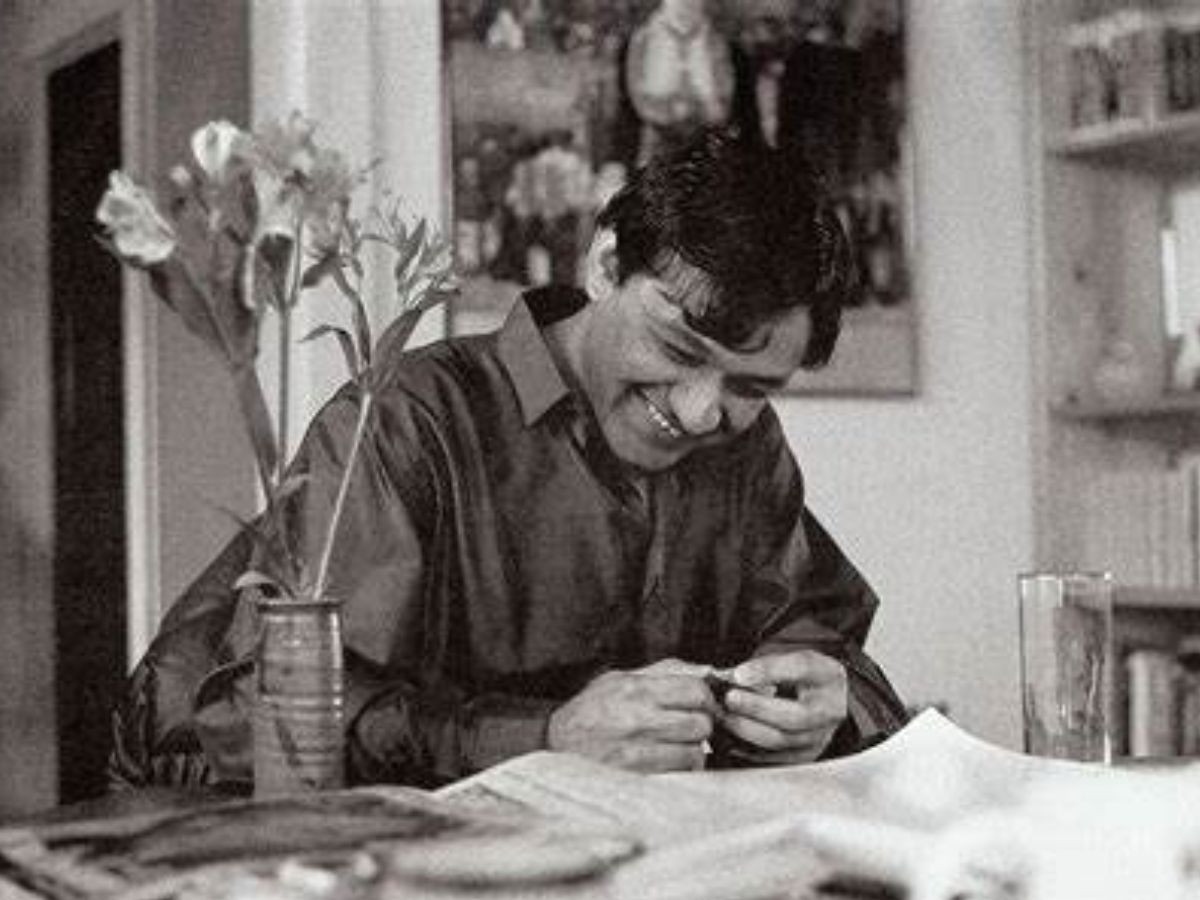

Few books in the history of academia have had as profound an impact as Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

(quick glossary interlude! The term ‘pedagogy’ refers to the method and practice of teaching).

First published in 1968 in Brazil, this work has gone on to shape the way people around the world think about education. It is the third most-cited book in all of the humanities, a testament to its lasting influence on scholars, educators, and activists alike.

But why has Pedagogy of the Oppressed resonated so deeply?

To begin answering these questions, we might start with a broader inquiry: What does it mean to be educated?

A possible answer to this question is that to be educated is to possess a vast store of knowledge, delivered efficiently and effectively into one’s mind, to be accessed and used at will.

But for Freire, education is not simply about the passive transfer of information. It is about the transformation of the educated subject.

He argues that the ontological vocation of human beings, that is, their fundamental, existential purpose, is the drive to become more fully human.

(quick glossary interlude! Ontology is the study of existence, a.k.a what exists and how does it exist? The term ontological vocation then, broadly, refers to our inherent purpose or calling as human beings).

At the heart of Freire’s work is the belief that human beings exist within an ongoing contradiction—a constant tension between oppression and liberation. Just as we oscillate between hunger and satisfaction, between exhaustion and rest, we are always moving between forces that seek to limit us and forces that seek to free us.

We are born into a world teeming with possibilities. The sheer number of choices we could make, the vast potential paths our lives could take, is overwhelming.

Faced with this weight, people often seek comfort in external structures—ideologies, religion, nationalism, consumerism—systems that provide easy answers to life’s complexities.

In exchange for stability and certainty, individuals often surrender large pieces of their own identity, shaping themselves in the image of these external authorities rather than defining themselves on their own terms.

Recognizing this reality raises two crucial questions.

What role does education play in shaping individuals who either passively accept their conditions or actively challenge them? And ultimately, is our current schooling system a tool of oppression or liberation?

To answer this question, Freire conceptualizes the “banking model of education”.

The metaphor is deliberate: in this model, students are passive recipients of knowledge. The teacher owns the knowledge. The student’s role is simply to absorb and regurgitate.

The banking model can be effective if the goal of education is simply to efficiently distribute knowledge, ensuring that most people memorize and internalize a predetermined set of information decided by an authority.

You can’t really dispute the fact that this is an excellent way to train people to produce the right answers on standardized tests.

But what exactly is it that we are testing?

If the purpose of education is not just to memorize facts but to cultivate critical, engaged thinkers who can understand and navigate a complex world, then the banking model fails miserably.

Freire argues that this is precisely the kind of education that produces citizens who passively consume media, mindlessly internalizing dominant narratives (which generally serve the state, oops).

When confronted with uncertainty, a student trained under this model will instinctively look to authority figures to provide answers, rather than develop the skills to critically evaluate a situation for themselves.

When people are trained from childhood to uncritically accept what they are fed, they become easy to govern, easy to manipulate, and even easier to oppress.

Freire’s theory is about developing a consciousness that understands oppression not just at a personal level but at a societal one. It is a call to collective, political action, one against authoritarianism in all its forms.

(quick glossary interlude! Authoritarianism describes a system where a single leader or a small elite holds concentrated power without being accountable to the larger public).

True education, Freire argues, must be about more than depositing information, it must teach people how to think.

Freire offers a powerful alternative to the banking model: “conscientização”, or “critical consciousness”. To to have critical consciousness is to be engaged in a process; it's an activity

By this logic, being educated is not a static state of being but an active, ongoing commitment.

But developing critical consciousness is not enough on its own. If critical thinking is driven purely by anger, it may simply replicate the cycle of oppression it hopes to dismantle. This is one of the historic dangers of many revolutionary movements: we risk turning the oppressed into the oppressor.

Freire argues that critical consciousness must be rooted in love. This might sound idealistic, but for him, it is a deeply political stance.

Love, in this context, means a genuine commitment to the well-being of all people—including both the oppressed and the oppressors.

This idea is radical. It challenges the notion that the struggle for justice is merely about reversing the power dynamic. Freire insists that both the oppressor and the oppressed are dehumanized by systems of domination.

At first glance, it might not seem obvious why the oppressor would be dehumanized. But consider this: is it truly fulfilling to have one’s sense of self tied to the ability to control, dominate, and suppress others? When your power depends on limiting another person’s humanity, are you truly free yourself?

The answer, for Freire, is no.

True liberation must be a process that frees both the oppressed and the oppressor. This is why education—real education—is more than just the transfer of knowledge.

Education should be about helping people develop the skills, awareness, and love necessary to transform both themselves and the world around them.

Freire’s “problem-posing” model of education offers a more effective and liberating education system.

One of the biggest shifts in the problem-posing model is that education is centered around dialogue between teachers and students rather than being a one-way transfer of knowledge. Instead of a teacher delivering a monologue in the form of a lecture, the classroom becomes a space for discussion.

This approach is this dialogical rather than monological.

The teacher may still possess greater knowledge and experience—they may have had this particular discussion hundreds of times before and can anticipate common questions, objections, and areas of confusion—but the dynamic is no longer one in which students passively receive information. Instead, they actively participate in constructing meaning.

For Freire, true learning happens when knowledge is co-created between teacher and student.

Rather than reinforcing a rigid hierarchy where the teacher is always the authority and the student is always the passive learner, this model recognizes that meaningful education can emerge from mutual respect and intellectual engagement.

The teacher’s role is to facilitate critical thinking rather than simply dictate facts.

Even when direct instruction is necessary, it should serve as a foundation for critical discussions rather than as an unquestionable truth to be memorized and repeated.

By shifting from a banking model to a problem-posing approach, we create learners who are not just knowledgeable but also capable of questioning, analyzing, and shaping the world around them.

Importantly, Freire’s philosophy is not about replacing one form of dogma with another. If students are being conditioned to adopt a narrow worldview—whether in the name of traditional authority or radical ideology—then they are not practicing the type of critical education he envisioned.

True critical consciousness means questioning all forms of imposed ideology, regardless of their source or stance.

Education should not create foot soldiers for a cause. It should nurture individuals who are willing to interrogate their own beliefs, challenge authority in all its forms, and remain open to the possibility that they too, might be wrong.

The creation of independent thinkers capable of engaging with the world in a way that is both critical and compassionate is possible. And it starts in your classroom, today.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ