February 5th 2025: a big part of me is deeply skeptical of the sincerity of the Pakistani state’s commitment to Kashmir liberation.

Intended to be a day of remembrance – to stand in solidarity with those living under decades of violent occupation and advocate for Kashmir's right to self determination – the Pakistani state’s display of camaraderie has historically been nothing more than an excuse to orchestrate an empty political spectacle, one that is more symbolic than it is substantive.

While collective solidarity is the most meaningful asset in our social and emotional repository, it is important to ask: do we truly stand for a free Kashmir, or only for a Kashmir whose liberation fits within Pakistan’s idea of nationhood?

The lack of genuine platforms centering voices from necessary stakeholders, that is, the people of Gilgit-baltistan, specifically of Pakistan administered Jammu and Kashmir, is glaringly obvious.

As Pakistan observes Kashmir Solidarity Day, it is worth turning inwards to contemplate the borders that run through our own solidarities—where they begin, who they extend to include, and who they willfully exclude when they run up short.

For over seven decades, Pakistan’s stance on Kashmir has been absorbed into its own nationalist rhetoric, used to justify military presence and geopolitical posturing, which directly contradicts its professed commitment to the UN Resolutions of 1948.

Can a nation that denies liberation within its own borders truly extend it beyond them?

Is the Pakistani state’s display of solidarity part of a larger call for freedom, or is it just another tool of political maneuvering?

In any case, it is worth using this opportunity to turn to an alternate source of solidarity: the poet’s memory.

“Your history keeps getting in the way of my memory,” writes the Kashmiri-American poet Agha Shahid Ali in “Return to Harmony 3,” a poem from his collection The Country Without a Post Office. This brief, curious gesture guides me as I read through Shahid’s work, greedily.

How does the poet's memory disrupt the fictions of the modern homogenized nation?

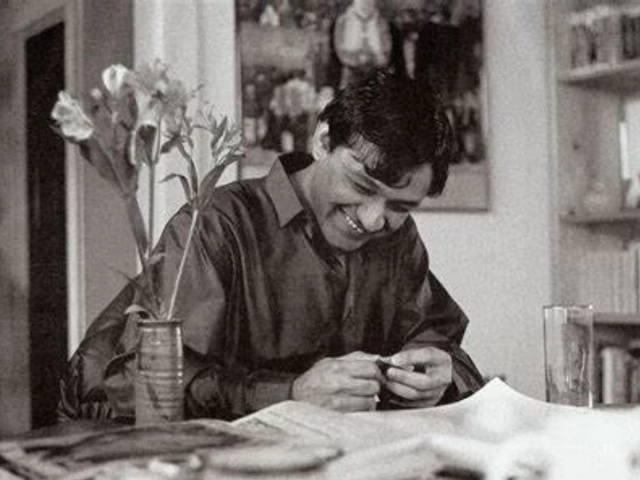

The late Agha Shahid Ali (1949–2001), a well-loved poet, translator, and teacher, is celebrated not just for his lyrical mastery and commitment to the craft of poetry, but also his profound, complex exploration of the politics of national belonging and exile.

A skillful blend of English with Urdu, Persian, and Arabic literary traditions, particularly the ghazal, his work is an enduring archive of tthe collective grief of a historically oppressed group of people whose psyhce is shaped by the violence of life under military occupation.

His most acclaimed collections include The Half-Inch Himalayas (1987), A Nostalgist’s Map of America (1991), The Country Without A Post Office (1997), Rooms Are Never Finished (2001), which was a finalist for the National Book Award, and Call Me Ishmael Tonight (2003), a collection of English ghazals published posthumously.

The Country Without a Post Office (1997) in particular, is a deeply evocative and politically charged collection of poetry that grapples with the devastation in Kashmir during the 1990s insurgency, reflecting the complete suspension of postal services and communications blackout that followed mass unrest in Kashmir.

The collection frames the silencing and historical earsure of the Kashmiri voices via a flurry of undelivered letters.

The titular poem envisions Kashmir in the 1990s as a haunted, abandoned post office, where the poet searches for words that can no longer reach their intended recipients.

‘Nothing will remain, everything’s finished,’

I see his voice again: ‘This is a shrine

of words. You’ll find your letters to me. And mine

to you. Come soon and tear open these vanished

envelopes.’ (Agha Shahid Ali, "The Country Without A Post Office")

The true subject of poetry – that "shrine / of words" – for Shahid, borrowing Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s famous epitaph, is “the loss of the Beloved”.

The link between poetry and separation from the beloved is fundamental to the Indic, Persian and Arabic traditions, and to the genre at large.

This calls to mind the opening of Mawlana Rumi’s Masnavi, “The Song of the Reed Flute”, one of the greatest poems in history, that begins with the mournful cry of the reed-flute, torn from its source, the reed-bed, lamenting its separation:

“Listen to the reed, how it tells a tale, complaining of separations.”

Here, the reed is a metaphor for the human soul, severed from its origins and longing for return to the source of creation.

The reed is also the poet’s instrument. Just as the flute's song is a cry for reunion, so is the pen's.

The writer’s pen, the qalm, itself a reed, wails in ink, longing for the wholeness of union beyond what can be articulated in language.

In some ways then, all poetry is a complaint of separation, a yearning for return to the beloved.

So what is the purpose of poetry?

This is an archive. I’ve found the remains

of his voice, that map of longings with no limit.

(Agha Shahid Ali, “The Country Without a Post Office”)

The poem, for Shahid, is an archive is testament to this yearning for wholeness. One that “announces heartbreak as its craft: a promise like that already holds its own breaking”.

Given the state of the world today, oftentimes I feel we are estranged from our own breaking. Our potential to carry out genuine efforts toward liberation intimately depends on our capacity to remain tender to pain.

That is why we write, continue to write, even with the knowledge that our words may never reach the beloved.

As we think of a way out of nationhood—as we imagine alternate futures—let us turn to the poets, who, in the space of their poems, create room for witnessing.

The poet’s longing is spread out across time, and so touches place ordinary logic cannot reach; the beloved exists in the past and the future, in memory and imagination, beyond what is possible in the present.

It is the poet's capacity to feel and relate their feeling in the space of a poem that moves us, that drives us toward those possible, liberated futures we yearn for.

When held to the stature of the beloved, even a homeland whose borders are impervious to letters is vulnerable to the mad, brave words of a poet.

I’ve found a prisoner’s letters to a lover—

One begins: ‘These words may never reach you.’

Another ends: ‘The skin dissolves in dew

without your touch.’ And I want to answer:

I want to live forever. What else can I say?

It rains as I write this. Mad heart, be brave.

(Agha Shahid Ali, "The Country Without a Post Office")

In his poetry – by way of his mourning work, his bearing witness to the grief of his people – Shahid offers us an imaginative field that becomes a site for the formation of a mad, brave self. In doing so, he exposes the violence that underpins the logic of ‘national interest’ and encourages us to be more wholly human.

About his takhallus (pen name) he says:

“They ask me to tell them what Shahid means: Listen, listen:

It means ‘The Beloved’ in Persian, ‘Witness’ in Arabic.”

(Agha Shahid Ali, “in Arabic”)

Witnessing is a deeply political vocation; the witness's poetic utterance is at once an act of mourning and memory-keeping.

A poet’s longing for the eternally absent beloved, that is a longing for a return to a whole self, reflects a deeper desire to be liberated from the material constraints of this world, to transcend into an immaterial future, into the domain of possible.

In an interview with Poets & Writers, when asked what inspires him, Shahid replied:

“Everything. Love, death...I mean what inspires poetry down the ages, I suppose. Anger-not too much anger, in my case, but definitely some amount of political rage at times. And language, just language.”

For any poet, the beloved beyond all else, is the letter itself – the word.

The poet keeps writing back to that country of language, with no return address, longing for the final return – for a homecoming, for union, for liberation.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ