Here's what your Pak Studies teacher forgot to mention...

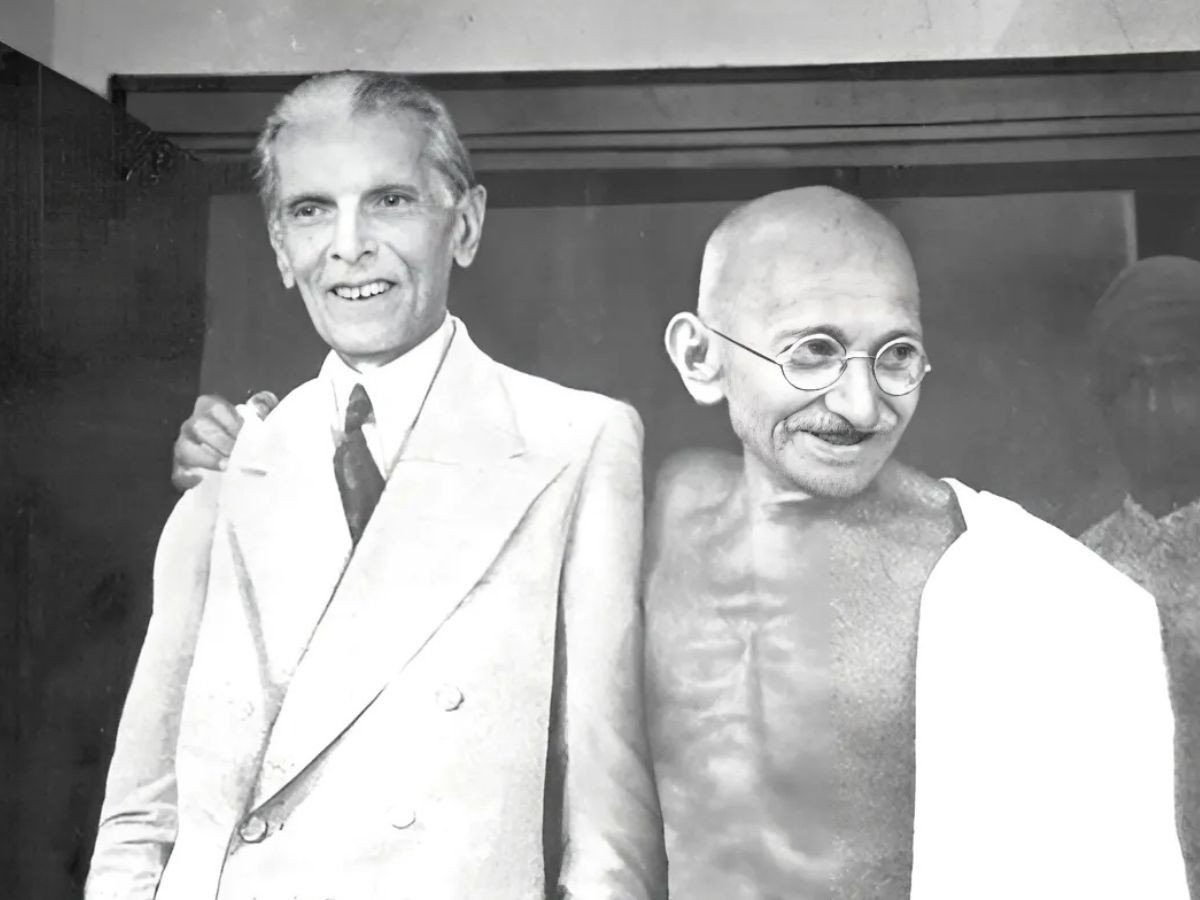

Growing up in Pakistan, it’s nearly impossible to separate the country’s history from the towering figure of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the Quaid-e-Azam, or “Great Leader.” His vision of Pakistan as a homeland for Muslims is deeply embedded in our national psyche.

What if we consider the possibility that this vision was less about safeguarding a unified Muslim identity and more about political maneuvering in the face of a collapsing colonial order?

What if the idea of Pakistan was not an inevitable outcome but a tactical move, shaped by the anxieties and ambitions of a few key players?

The foundation of Pakistan is often framed as the culmination of a centuries-old struggle to protect a unified Muslim identity in South Asia. But this narrative crumbles under scrutiny.

The goal of Pakistani nationalist historiography – i.e. the way history is recorded and presented – is to forge a particular kind of Pakistani identity.

The reality is that Indian Muslims were far from a cohesive group. They were divided along doctrinal, sectarian, and regional lines, with no singular political agenda.

As historians Sugata Bose and Ayesha Jalal argue, the idea of a unified Indian Muslim identity was more a construct of later scholars than a reflection of historical reality.

Pakistan’s nation-building project was rooted in a Muslim nationalism that emerged not long before the partition of the Indian sub-continent in 1947.

While ideas around the irreconcilable differences between Muslims and Hindus have their roots early on in the colonial project, the hasty development of the anti-colonial national projects from the 1920s up until the eventual split in 1947 exaggerated these differences considerably.

In the early 20th century, Indian Muslims were a diverse community with varying interests. Some aligned with the Indian National Congress, others with regional parties, and still others with religious organizations like the Jamiat Ulama-e-Hind.

The notion that all Indian Muslims shared a common political goal is a myth perpetuated by nationalist historiography, which seeks to forge a unified Pakistani identity rather than uncover historical truths.

Religion played a pivotal role in the anti-colonial struggles of the early 20th century, but not in the way nationalist narratives suggest.

Mahatma Gandhi, envisioned an India built on a coalition of religious communities, not Hindu dominance. Despite this, while he did not seek an avowedly Hindu India – much unlike the later Hindu nationalists – religion, in his view, formed the binding glue of the nation.

As a result, he inevitably embodied a deeply Hindu sensibility which inadvertently stoked fears among Indian Muslims who were worried about their place in a post-colonial India.

These fears were amplified by events like the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in 1920, which led to the Khilafat Movement—a mass mobilization of Indian Muslims seeking to protect the Ottoman Caliphate.

The Khilafat Movement, while a moment of unity for Indian Muslims, also highlighted the growing politicization of religious identity.

Despite alliances with the Congress, Muslim leaders like those in the Jamiat Ulama-e-Hind envisioned an India divided along religious lines, with separate laws and institutions for Hindus and Muslims.

This early fragmentation of Indian society into religious categories laid the groundwork for the eventual demand for a separate Muslim state.

By the late 1920s, the political landscape of India was shifting.

The Nehru Report of 1928, which proposed a federal India with a strong central government and no reserved seats for Muslims, deepened the divide between the Congress and Muslim leaders.

Jinnah, once a member of the Congress, turned to the Muslim League, feeling that the Congress had failed to address Muslim concerns. This marked the beginning of his transformation into the “sole spokesman” for Indian Muslims.

The idea of Pakistan as a separate nation for Muslims emerged in the 1930s, but it was far from a cohesive vision. Initially, it was a vague concept, with no clear geographical boundaries or political structure.

Jinnah and the Muslim League used the idea of Pakistan as a bargaining chip to secure Muslim interests in a post-colonial India. The 1940 Lahore Resolution, which called for independent states for Muslims in the northwest and east of India, was less a blueprint for a nation and more a political maneuver.

The creation of Pakistan was not inevitable. Even as late as 1947, the geographical boundaries of the new nation were uncertain.

The idea of Pakistan faced significant opposition from within the Muslim community itself.

The Unionist Party in Punjab, for example, saw no benefit in a separate Muslim state. Similarly, many religious scholars, particularly those from Deoband, opposed the idea of Pakistan and instead advocated for a united India with cooperation between religious communities.

Jinnah’s ability to rally support for Pakistan was not based on a unified Muslim identity but on exploiting existing fears and anxieties.

The slogan “Islam in Danger!” became a powerful tool for mobilizing rural voters in Punjab and other Muslim-majority areas. Yet, this mobilization was not universal. Many Indian Muslims, particularly those in minority regions, saw little benefit in the creation of Pakistan.

The partition of India in 1947 was a chaotic and violent process, marked by mass migrations and communal violence. The creation of Pakistan did not resolve the tensions between religious communities; instead, it exaggerated them.

The Pakistani state, founded on the idea of safeguarding Muslim interests, has since relied on the narrative of “Islam in Danger” to justify its existence. This narrative has perpetuated a hostile relationship with India, that, on the other side of the border, is witnessing a terrifying rise in right-wing Hindu nationalism.

The BJP’s rhetoric of a "Hindu Rashtra" (Hindu nation) echoes the same fears and anxieties that once fueled the demand for Pakistan, revealing how the colonial legacy of religious polarization continues to shape South Asian politics. The rise of Modi and the BJP is not an isolated phenomenon but a direct consequence of the historical processes that divided the subcontinent.

The problems Pakistan faces today—political instability, sectarian violence, and regional tensions—can be traced back to the hasty and uncertain conditions under which the nation was formed. The idea of Pakistan was not a long-standing project but a response to the immediate political realities of the 1940s.

Growing up in Pakistan, I was always struck by the inconsistencies in the nationalist narrative we were taught. From school textbooks to family discussions, there was always something that didn’t quite add up.

If there is one lesson to take away, it is this: a Pakistan constantly at odds with its history has no real future. The path forward requires a reckoning with the past, an acknowledgment of the complexities and contradictions that shaped our nation, and a move towards a more inclusive and less adversarial vision of identity and nationhood.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ