The Leap Day treaty signed at Doha between the United States and the Taliban, which stipulates a 14-month American withdrawal in return for Taliban guarantees of inhibiting international militancy, officially begins the end of the United States’ longest and perhaps least understood war. Provided that the deal holds, the Americans will leave in 2021, bringing their sojourn in Afghanistan to a full 20 years. In turn, the withdrawal of foreign forces, a major theme in Taliban recruitment, should seem to preclude further militarisation from the insurgents’ side. But there remain risks involved in Afghanistan, not least because the coalition installed and held together by American patronage has been excluded from the talks and is also on the brink of collapse.

On the one hand, the treaty should underscore the futility of an Afghan war that could have been prevented at the outset with just a little more political restraint and wisdom. Both the Taliban’s hesitancy in evicting Osama bin Laden’s network and American haste in driving the Taliban to the maquis, and ruthlessly pursuing them even after the emirate had collapsed, have proven foolish and costly. So to have ideas of inherent Taliban radicalism and division that hitherto precluded meaningful talks. The insurgency was never as divided as claimed, and certainly less on ideological grounds than any other grounds. It is encouraging that the deal has been welcomed by both deputy leaders – Abdul Ghani Baradar, who signed it at Doha, and Sirajuddin Haqqani. Not only were the pair influential strategists in the insurgency, organising its structure and operations in southern and eastern Afghanistan respectively, but they also played key mediating roles when frictions threatened to split the Taliban, in the late 2000s and mid-2010s respectively. That both commanders have endorsed the plan is therefore encouraging for the prospect of wider Taliban acceptance.

But the deal is also notable for whom it excludes. The United States was careful in the treaty to counteract every mention of the “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan”, the name by which the Taliban refer to themselves, with a disclaimer that it did not recognise them as a government. But nonetheless, the talks have pointedly excluded the same political class, largely comprising of former militia commanders and government bureaucrats, that the Americans spent a generation installing in Kabul. That the Kabul government is weak was always self-evident; the 2019 election yielded only a million votes throughout the country, a statistic that does not inspire confidence in its influence. What is more dangerous is that the Kabul government today is more divided than it has been in the past.

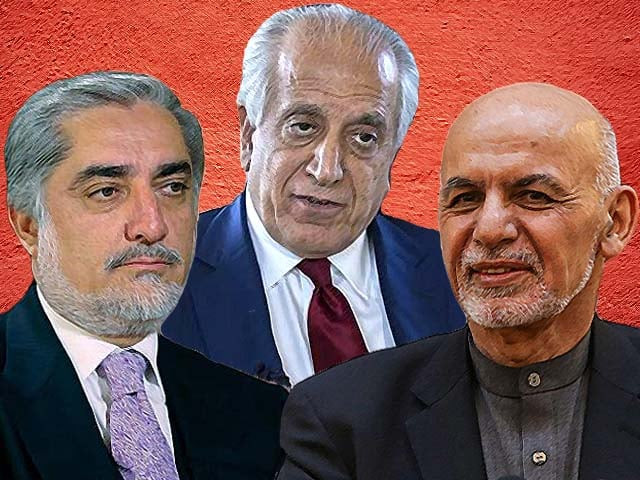

Abdullah Abdullah, runner-up in the last three elections (2019, 2014, and 2009), was only persuaded to accept the 2014 result after months of negotiations through America’s then-foreign minister, John Kerry. This organised a rather informal arrangement where he, taking the unusual title of “chief executive”, shared power with Ashraf Ghani, the official winner. After the result repeated itself in 2019, however, Abdullah seems to have decided to dispense with the formalities and in February 2020 began to set up a parallel government to Ghani’s. This escalates the slow-burning tension between the coalition of largely non-Pashtun peripheral military-political adventurers, who favour regional autonomy, in the periphery – such as Abdul-Rashid Dostum, Ata Noor, and Muhammad Mohaqiq in northern Afghanistan – and Ghani’s centralist, mainly Pashtun network in Kabul. This conflict, inevitably taking on an ethnic tinge, came into particularly sharp focus after Ghani sacked Dostum, then his deputy, for assorted alleged abuses in 2016; the regionalists sniffed a centralist power grab. But it has gone on almost as long as the war itself.

The regionalists, while a mixed and often fractious lot, are nonetheless united in their dislike of Kabul centralism. Benefiting from the value of militias in counterinsurgency, they have plenty of firepower; indeed in northern Afghanistan it has largely been Dostum and Noor’s coalition fighting Taliban advances in recent years. Having comprised the bulk of the northern militias who fought the Taliban emirate before 2001, it is by no means certain that they would accept the Doha Accord; indeed they have long viewed Zalmay Khalilzad, the American signatory of Afghan background, as partial to their Pashtun rivals in Kabul, and may simply see the Accord as another deal between Khalilzad and the majority-Pashtun Taliban.

Ghani’s occasional half-hearted attempts to rein in militias – often focusing on non-Pashtun militias such as Dostum’s lieutenant Nizamuddin Qaisari in the north – have been further complicated by his lack of sizeable military force. Until now, the United States was the main guarantor for his government in Kabul: the second guarantor, the secret service inherited from the communist period and once presided by his deputy Amrullah Saleh, is hardly encouraging, staunchly opposed as it is to any accord with the Taliban insurgency. In spite of talk about inter-Afghan negotiations, the insurgents have continued to behave as a shadow government – and this is as much a potential threat to Kabul as the northern regionalists.

Should it occur, an American withdrawal and a Taliban crackdown on foreign extremists would certainly undermine the most vexatious aspect of the Afghan war – the foreign fighters on each side. The more complicated stage of coming to a peaceful compromise will have to be left to the Afghan protagonists themselves.

What does the future hold for Afghanistan after the Doha deal?

The more complicated stage of coming to a peaceful compromise will have to be left to the Afghans themselves

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ