This article is the second in a two part series which looks at pre-partition and post partition events that led up to Pakistan being declared an Islamic republic. Read part one here.

~

In the 1945 elections, although Thanvi had died, the Muslim League had the support of one of his protégés, another Deobandi scholar named Shabbir Ahmad Usmani. The ulema offered their help to the Muslim League and sent 24 scholars, including Hasrat Mohani,across Uttar Pradesh (UP) for campaigning. Mohani later became a member of the UP assembly. Usmani’s JUI lent their support to the League officially and Nawab Ismail Khan recognised the leadership of the ulema led by Usmani, in his official capacity as chairperson of the Committee of Action.

Islam's name was taken by Jinnah and League members repeatedly after the 1937 by-elections. In 1940, Jinnah told a student,

“I seek to secure the land for the mosque; once that land belongs to us, then we can decide on how to build the mosque.”

Religious slogans were raised frequently during his speeches. He changed his attire and visited mosques to reach out to the Muslims. His letter from November 18, 1945 to Pir Sahib of Manki Sharif, who was situated in modern day Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, promised that the Constituent Assembly would enact laws consistent with the Shariat. Soon after the Lahore Resolution, the UP Muslim League created a committee which included its representatives as well as the ulema for the purpose of crafting an Islamic constitution for Pakistan. The chairperson was Syed Sulaiman Nadwi, an orthodox scholar from Nadwatul Ulema. Hence it was with some justification that, after partition, the government was being asked to make Pakistan an Islamic state.

Liaquat Ali Khan was cognisant of this fact and the opposition of the minorities. After the Objectives Resolution was passed, a special committee was created called “Talimaat-i-Islamia” which comprised of orthodox ulema. However, in 1950, one of the committees of the Constituent Assembly, the Basic Principles Committee, gave the first draft of the constitution which included the Objectives Resolution “as a directive principle of state policy” but it was “not to prejudice the incorporation of fundamental rights in the Constitution.” GW Choudhory noted in his book, Documents and Speeches on the Constitution of Pakistan that the ulema were not at all happy with this, but there was little they could do about it, despite their vast appeal among rural and some segments of urban masses.

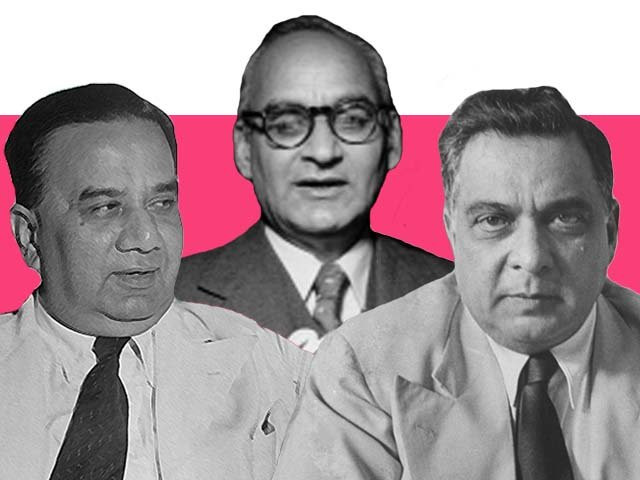

In 1950, the report of the Committee on Fundamental Rights and Matters relating to minorities was accepted. Offering equal rights to its citizens, it was generally well-received. Safdar Mehmood, in his book Constitutional Foundations of Pakistan wrote that Khan claimed that “all essential rights have been provided” by the report. Sadly, in 1951, Khan was assassinated and Khwaja Nazimuddin became the prime minister. GW Choudhury notes that this is when ulema began to gain power as Nazimuddin was sympathetic towards them. Meanwhile, the Bengalis opposed the first draft on matters totally unrelated to rights of minorities, and so in 1952, another draft was presented.

While secularists such as Hamza Alavi claim that this draft was made overtly Islamic to silence Bengalis in the name of Islamic unity, the fact is that only a few clauses were introduced that were different from the first draft such as the requirement that the head of state be Muslim and that no laws repugnant to the Quran and Sunnah be promulgated. Hamid Khan in his book Constitutional and Political History of Pakistan, stated that the second draft also gave more leeway to the Bengalis, which angered the Punjabis. Since the head of state did not have much power and was largely ceremonial, Hamid opined that this was to pacify the growing Islamist agitation and maintain the semblance of equal rights. Either way, the aforementioned Muslim-centric clauses were opposed by Chattopadhyaya, Barma, BK Datta and Begum Shah Nawaz. The second draft also assigned the task of checking the repugnancy of laws with Quran and Sunnah to the Supreme Court and not with a body comprising entirely of orthodox ulema.

This last point is significant as the ulema always rejected that Ijtihaad (independent reasoning) or legislation on Islamic laws could be done by anyone elected to Parliament or the judiciary. They believed that a person must be of a certain Islamic qualification to be a Mujtahid (original Islamic authority). However, according to Professor IH Qureshi, Ijtihaad can be done by the elected legislature too on the basis of Muslim Law and so, this a sizeable point of contention between modernists and Islamists.

Islamists showed their street power for the first time with the Anti-Ahmadiyya riots of 1953. Nazimuddin was dismissed subsequently during the same year further delaying the constitutional work of the country. By 1955, the new governor-general, Iskander Mirza, who wielded more power than his predecessor Ghulam Muhammad, was openly against the inclusion of religion in politics.

He said,

“We can’t run wild on Islam; it is Pakistan first and last.”

However, Muhammad Ali Bogra, who was prime minister at the time, presented the third draft in 1953 which is commonly known as the Bogra formula. The Jamaat-e-Islami was satisfied with the third draft and declared,

“…the proposed constitution of Pakistan was to a very great extent Islamic in character.”

The next prime minister, Chaudhry Muhammad Ali, accelerated work on the constitution in 1955 and, with the help of stalwarts such as HS Suhrawardy and AK Fazlul Haq, the new draft constitution was presented within months on January 9, 1956. The Objectives Resolution was again included in the preamble with a new clause stating that Pakistan would be a democratic state based on Islamic principles of social justice. It was here that Pakistan was first formally addressed as the “Islamic Republic of Pakistan.”

The political reaction to the draft was mixed. According to Hamid Khan, it received positive views from Muslim League, the Bengali United Front and Nizam-i-Islam while the Bengali Awami League, while some Hindu and Leftists parties in that province demanded it be scrapped. The Awami League was particularly irked with the powers given to the centre and the rejection of its 21 point programme. As many as 670 amendments were moved of which some were accepted, and subsequently, the draft constitution was finally adopted on February 29, 1956.

Equal citizenship was again made a part of the new constitution under inalienable fundamental rights. The Directive Principles, that were included in the constitution but were not made legally enforceable, talked about Islam and its promotion by the state. Other religions were also not barred to promote themselves, but it was simply that they would not be promoted by state. The Directive Principles also pledged the elimination of riba, more commonly known as usury. The constitution also stated that the president had to be Muslim whereas the proposal for the same requirement to be applied to the post of vice president was rejected. According to the constitution of 1956, a non-Muslim could become speaker and so, in absence of the president, could become the head of state temporarily.

Was the 1956 constitution based on Jinnah’s ideals? An accurate answer would be that it was a compromise between Islamists, modernists and secularists suited for the political reality of that particular time. The role of Islam in the creation of Pakistan cannot be ignored nor the fact that the majority Muslims inhabiting it were largely conservative and as a recent poll showed, still are largely in favour of orthodox Islamic Shariat. Choudhury wrote that the ruling Pakistani elite, especially Liaquat and Nizamuddin were never secular in the western sense. That being said, they were not as concerned with the pacification of Islamists as they were with the portrayal of Pakistan’s image to the largely secular world.

The 1956 constitution impacted subsequent constitutions and generated opprobrium among secularists and to a lesser extent, modernists and even certain Islamists. Today, as real power is vested in the legislature, appeals for social change must be made to the masses rather than a government that is merely their representative. Jinnah, whatever he may seem to different people, was undoubtedly a committed democrat. This was his ideal and Jinnah’s Pakistan always meant a Pakistan where the will of the people was destined to chart the future course of the country.

[poll id="804"]

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ