Was Pakistan always destined to become an Islamic republic? - Part 1

After partition, Islamists began demanding the Islamic state that they believed Jinnah had promised

This article is the first in a two part series which looks at pre-partition and post partition events that led up to Pakistan being declared an Islamic republic. Read part two here.

~

Saturday, 29 February 2020, will mark the 64th anniversary of the day when Pakistan was formally declared an Islamic republic. However, was Pakistan always destined to be a Muslim state? This was one of the critical questions faced by Pakistan’s founders and the subsequent leadership soon after the country’s independence in 1947. The question, however, was not new. Ever since the Muslim League’s Lahore Resolution of 1940 and Jinnah’s enunciation of the two nation theory, both opponents and supporters of the League had wondered as to what kind of state Pakistan was going to be.

Naturally, eyes turned towards the founder of the nation and his speeches for guidance. Jinnah had three answers on record to the aforementioned question. Firstly, he had stated that Pakistan would not be governed by “priests on a divine mission.” Secondly, he had also said that the constitution of the country would be determined by the representatives people and finally, that Pakistan’s constitution would not be in conflict with Shariat.

While secularists and Islamists offer their own explanations to reconcile these three seemingly contradictory statements, to Jinnah and his lieutenant, Liaquat Ali Khan, there was no contradiction to begin with. This is best described by Khan in his speech before the constituent assembly when he moved the Objectives Resolution on 7 March, 1949,

“...all authority should be exercised in accordance with the standards laid down in Islam so that it may not be misused.”

He also added,

“...in accordance with the spirit of Islam, the preamble fully recognizes the truth that authority has been delegated to the people, and to none else. This naturally eliminates any danger of the establishment of a theocracy.”

To Khan, simply mentioning the name of Islam in a preamble to the constitution was not theocratic. To him, the state became a theocracy when power went into the hands of the undemocratic, hand-picked orthodox ulema, to which Jinnah had alluded to as “priests on a divine mission.”

Khan further stated that the principles of democracy, freedom, equality, tolerance, and social justice needed to be “observed in the constitution as they have been enunciated by Islam”, adding that it was necessary to qualify these terms further in order to give them a well-understood meaning. This was not unheard of, seeing as how in every country, free speech is qualified to exclude hate speech and therefore, tolerance does not extend to hate groups. The only difference was that Khan wanted the qualifications to come through Islam.

He went on to say that,

“the state is not to play the part of a neutral observer, wherein the Muslims may be merely free to profess and practice their religion, because such an attitude on the part of the state would be the very negation of the ideals which prompted the demand of Pakistan, and it is these ideals which should be the corner-stone of the state which we want to build.”

This is in line with what Jinnah said during his address to the Karachi Bar Association on January 25, 1948,

“No doubt, there are people who do not quite appreciate when we talk of Islam...Islam is not only a set of rituals, traditions and spiritual doctrines. Islam is a code for every Muslim which regulates his life and his conduct in even politics and economics and the like.”

Adding,

“Why this feeling of nervousness that the future constitution of Pakistan is going to be in conflict with Shariat Laws? Islamic principles today are as applicable to life as they were 1,300 years ago. I could not understand a section of people who deliberately wanted to create mischief and made a propaganda that the constitution of Pakistan would not be made on the basis of Shariat.”

We must also highlight Jinnah’s speech to the constituent assembly on August 11, 1947 in which he cemented religious freedom and equal citizenship as state policies. There is no contradiction between the two speeches once we realise that what Jinnah meant when he talked about Islam and Shariat was in fact a modernist version of Islam, espoused by the likes of Allama Iqbal and Muhammad Asad, and not the orthodox version of Islam propagated by Maududi and Shabbir Ahmad Usmani. Khan was also of the same view and this shall become clear once we see how the 1956 constitution was framed seven years after the Objectives Resolution was moved in the Constituent Assembly.

On March 7, 1949, Khan’s motion was opposed by non-Muslim members of the Assembly, Prem Hari Barma and Sris Chandra Chattopadhyaya. Over the next few days, they along with the other non-Muslim members such as BK Datta and Professor Chakravarty moved a large number of amendments, focusing on parts where phrases like “sovereignty belonging to God” and “state principles being enunciated by Islam” were mentioned.

The amendments, however, were rejected 21 to 10 as Professor IH Qureishi, Sardar Abdur Rab Nishtar, Shabbir Ahmad Usmani, Begum Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah, the leftist Mian Iftikharuddin and others voted against them noting that non-Muslim members also believed in God and should have no objection to His sovereignty, and that the resolution was in line with demand of Pakistan based on particular ideology and pledges, while reassuring them that they believed that power is delegated to the people which includes both Muslims and non-Muslims. Winding up the debates, Liaquat Ali Khan said,

“We are guaranteeing you [non-Muslims] your religious freedom, advancement of your culture, sanctity of your personal laws, and equal opportunities, as well as equality in the eye of the law.”

The Objectives Resolution however did not pacify some of the Islamists either. One of the key figures of the era, the head of Jamat-i-Islami, Maulana Maududi, is reported to have said that the Resolution was “such a rain which was neither preceded by a gathering of clouds nor was it followed by vegetation.”

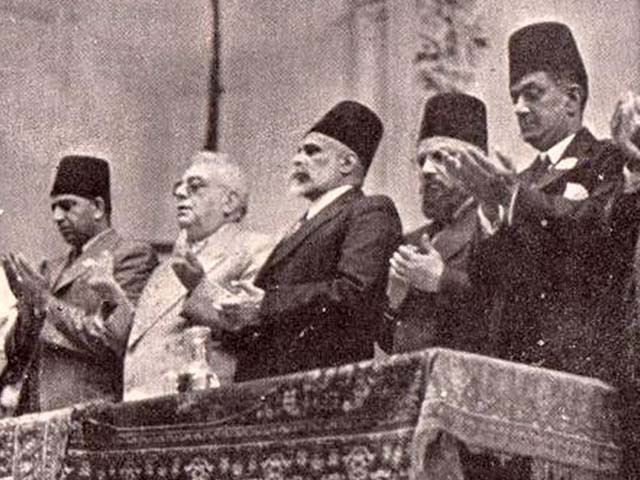

After partition, he and other Islamists such as Majlis-i-Ahrar and Shabbir Ahmad Usmani’s Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam (JUI) began demanding the Islamic state that they believed Jinnah and Muslim League had promised the Muslims. Let us examine whether there was any truth to this claim.

In 1937, during the by-elections, the Muslim League’s nexus with a faction of the Deobandi orthodox ulema began. One of the most prominent members of the ulema was Ashraf Ali Thanvi whose fatwa endorsing a League candidate in Sahranpur was plastered all over the constituency. He sent a questionnaire to the League which was responded to by none other than Nawab Ismail Khan assuring him of the Islamic credentials of the Muslim League. In 1939, Thanvi’s fatwa endorsing the entire Muslim League called “Tanzim-al-Muslimeen” was read out at AIML Patna Session by Zafar Ahmad Usmani. During the same session Jinnah met with a delegation of Deobandi Ulema where he announced that Islam was a complete code of life and cannot be separated from politics. This was plastered on the front page of his newspaper by Maulvi Mazharuddin, the editor of Al-Aman, Delhi who ultimately gave Jinnah the title 'Quaid-e-Azam'. This was repeated by Jinnah to Gandhi in 1944 during their famous talks as the basis of the Two-Nation theory.

Read part two here.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ