“This isn’t a tale of derring-do, nor is it merely some kind of ‘cynical account’; it isn’t meant to be, at least. It’s a chunk of two lives running parallel for a while, with common aspirations and similar dreams.”

When Ernesto “Che” Guevara wrote these words for his memoir The Motorcycle Diaries, one of the ‘two lives’ he was referring to may have belonged to Zenith Irfan, whose biopic Motorcycle Girl premiered last month.

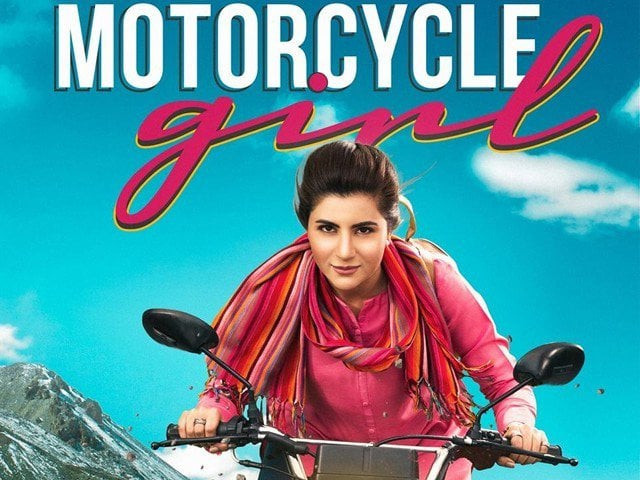

Irfan was 11-months-old when her father passed away, leaving behind a trail of unfulfilled dreams and a spray of handwritten letters. He had pined for an opportunity to travel through Pakistan on a motorcycle. Twenty one years later, Irfan made the journey with five men, including her brother, travelling northeast from Lahore to Khunjerab Pass on the Chinese border. Hoping to connect to a father she never knew, and wanting to reconnect with a country she thought she did.

The film is nothing like that.

Alfred Hitchcock described drama as life with the dull bits cut out. Hence actor-writer-director Adnan Sarwar keeps chipping away at the life of the real Irfan, until nothing remains but a heavily fictionalised account of her life.

The film reduces Irfan’s odyssey to the story of a girl who is harassed by her van driver, persecuted by her boss, ridiculed by her office crush, and railroaded by her fiancé. The men in her life are reprobates, while the solution to her troubles lies in a road trip she must make on (viola!) a motorcycle, epitomising her freedom and escape, à la The Girl on a Motorcycle (1968).

This, I believe, is a fatal flaw.

Trading down Irfan’s life so it becomes an “every girl story” was a gamble that paid off in the short term. What the fictionalised Irfan went through angered every female and embarrassed many men, but does the solution apply to all women? Or even most women? By eliminating the five men from Irfan’s journey and juxtaposing her travels with her tribulations of the past, Sarwar overreached. He took too long to setup her frustrations, her journey – both physical and spiritual – and her dreams. On second thought, even her dream belonged to her father.

Motorcycle Girl could’ve been a moving story of the love between a father and a daughter, if Sarwar hadn’t strived to examine every possible emotion on the spectrum of human existence. Not for a moment do we doubt Sarwar’s honesty and passion for filmmaking, or his urgency to tell a tale he feels is authentically Pakistani. But a road trip movie guarantees certain elements. And when it’s positioned as a true story, one wants it unmitigated. Upon learning that major chunks were formatted to fit the narrative, one no longer knows who to trust.

Photo: Giphy

Photo: GiphySohai Ali Abro as Zenith Irfan truthfully captures the frustrations of a helpless scarecrow being pecked at by merciless birds. Through her powerhouse performance, she’s left her competition miles behind. With its lifelike characterisation, realistic observations and sporadic quips, the film keeps drawing laughs and cheers – a testament that Sarwar had his finger on the collective pulse of middle class Pakistani women.

The film was shot on a shoestring budget of Rs25 million, but even that doesn’t justify the slipshod screenplay. In its attempt to appear stylistic, the writing seemed choppy, owing to its gratuitous transitions between the 'before' and 'after' the journey timelines.

Which brings us to an important question: why didn’t Sarwar stick to the original story?

In the classic ‘art imitates life imitates art’ milieu, women have always been objectified in Pakistani media. The exception is escapist novels spearheaded by Razia Butt, whose heroines were masters of their own destinies, always stirring a mini revolution, and consistently coming out on top. Escapist, because even today a woman has to come from a certain background, live in certain cities, and belong to a certain class to enjoy the freedoms extended toward her, albeit begrudgingly.

Starting on the right foot by making rocial (romantic-social; remember you read it here first and I coined it!) films till the 70s for enlightened audiences, Lollywood retrogressed into vendetta films that saw the number of movies released annually dwindle from over 50 to under five. Meanwhile, crimes against women soared, with honour killing topping the list. Elected officials plundered national resources. The country tumbled into moral murk. With no respite in sight, artists marched forward to a rescue. Unfortunately, artists are notorious for vending dreams.

Through Motorcycle Girl, Sarwar is out to sell a dream. A dream where a lone woman can travel through treacherous terrains alone on a motorcycle, and remain unscathed. Where she can revolt against a patriarchal society without chastisement or consequence. Where she can win, without dispensing a sliver of actable advice. It’s clear Motorcycle Girl is not about women’s liberation; it’s about riding the wave of women’s liberation, and hoping to be remembered as the one that instigated it.

I’ll never forget the hush that afflicted women as the end of the film drew close. Women with sisters, mothers and even daughters of tender ages who’d hoped to be bewitched by a true story of courage, hope and resilience. As if it was the start of a revolution, and they didn’t want to miss it. How miffed they must’ve been to realise they were on the wrong bus! For in his zeal to turn Irfan’s life into a film, Sarwar forgot that empowerment doesn’t come from displaying oppression – it comes from showing them how to deal with it.

Che Guevara would’ve been disappointed.

What Sarwar could’ve done was to stay faithful to the genre of his story. Superficially, it could’ve been about a daughter out to realise her father’s dream, but on an existential level, he could’ve turned it into a conflict of ‘woman against society’. She could’ve fought to uplift the women she met on her way, only to realise how deeply entrenched the traditions remain. At the end, she would have realised that to change the world, she must change herself first.

There were a million solutions. This is just a crude one.

Maybe Che wasn’t referring to Alberto Granado or Irfan as he talked about “two lives running parallel”; maybe he was talking about all of us. Our whole lives we compete against ourselves, our true potential at loggerheads with our aspirations. Like a train running over a bridge, the shadow caught in the flowing stream down below.

For a fleeting moment, we can become anything – everything – we were meant to be. And sometimes, before we can choose, it’s gone forever. Eclipsed by the dancing dust particles called the past.

Motorcycle Girl had its chance.

Photo: Giphy

Photo: GiphyAll photos: Screenshots

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ