After premiering at the Manchester International Festival 2017, it is now on display at Dolmen Mall, Clifton till January 15, 2018. It is a collection of stories from the people who “left their homes and crossed borders during the 1947 Partition of the Indian subcontinent”. SOC picked up the lives of everyday people (like you and me) and presented them through the use of multi-faceted mediums such as short documentaries, installations, projection room, pop-up museums, and virtual reality, as well as sound and music.

https://www.facebook.com/socfilms/videos/1977201415629613/

In a way, I felt that it was a very smart use of modern day technology. How else could they capture and ultimately present a 360-degree experience of Partition-era architecture? The exhibit included very graphic depictions from survivors, including short documentaries, photographs, audio clips, and recreating the insides of abandoned havelis (manors).

Starting off from the survivors’ accounts, we walked through a “safar nama” (itinerary) – a darkened walkway, which I suppose was meant to be likened to somebody charting an unknown territory. In going through this section, we could only wonder what went through the minds of people who were a part of this mass migration. They, too, must have wondered: where are we going? What is going to become of us, our homes, our belongings, and everything that we are leaving behind? Will we ever come back?

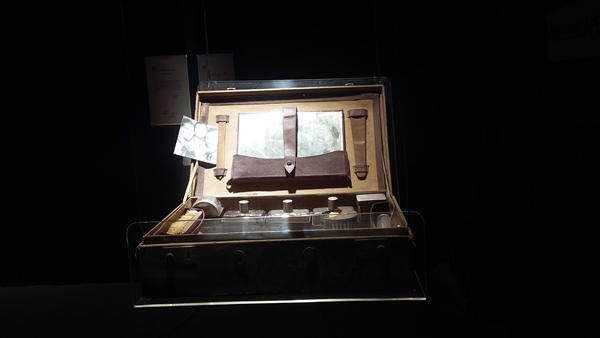

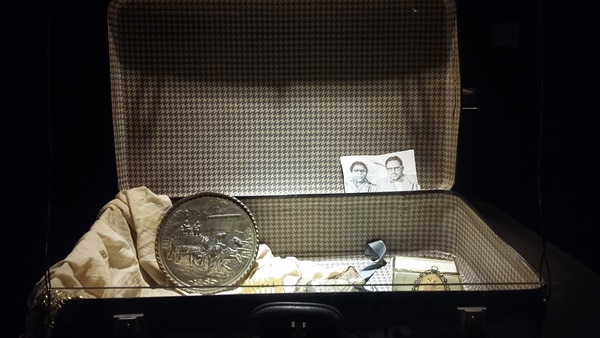

This led to the “Suitcase of Memories”, a section where I all but broke down. These suitcases contained a few meagre belongings of people who had escaped their homes in a hurry – their only aim at that point in time being to escape the riots and rioters. One suitcase had several cologne bottles and a shoe brush. Another seemed to be a vanity box of sorts, with a mini jewellery box, a hair brush and a pocket mirror. And yet another was perhaps a treasure chest – holding what seemed like a precious coin, which for all we know was a collectors’ item for the owner. Who knows?

While these items are pretty much insignificant to the grand scheme of this exhibit, they are otherwise priceless and say so much about that era; the thought (or lack of) given when figuring out what to carry along when trying to escape the impending threat of ruthless insurgents, and simultaneously the need to cling to physical items that give an otherwise surreal meaning to our lives. But more importantly, these suitcases of memories showed just how unprepared and, most likely, unwilling these people were to leave behind their homes and their belongings.

In a sense, we felt an absence of origin while making our way through the display. Listening to a lady talk about the time she spent with her best friend under a tree, and an elderly gentleman who recalled precise details of his mother’s death at the hands of the mob, gave us a more personal feel to the events of Partition, which brought into existence the country we now call home. Looking at the hair brushes with the hair still visible was so relatable, as that is exactly how I leave things behind when I am in a rush; clothes scattered everywhere, random newspapers and personal items strewn about the room.

There was a very familiar touch to anyone viewing the same, in that it literally personified the home as a living, breathing form which we often take for granted today. What would I take along if, for all practical purposes, I was pushed out of the place I called home?

The timing of this exhibit is pertinent, since 2017 marked #70KiAzaadi, for both India and Pakistan. But it’s important to note that it was an azaadi (independence) not just from each other, but for each other. While walking through Home 1947, I recalled the few stories my daadi ( paternal grandmother) told us about her personal experience. She talked about the train that crossed the border into Pakistan and passengers were massacred; her eyes welled up when telling me,

“Wo hamare apne log thay saare. (they were all our people)”

I know in my heart that regardless of whatever background the victims held, she genuinely felt that they were all her own people.

Both my daadi and naani (maternal grandmother) lost a brother in the disturbances that followed; he was due to appear for some exam and never came back home thereafter. To date, my family considers him missing; in the absence of any other news, what else do we think?

I thought of my taaya (uncle), as we both watched the TV show Dastaan, and after each episode, we would have long conversations, wherein he confessed that each viewing made him relive the times of Partition. I will never know for sure if those memories were painful recollections, or if there were memories that he reminisced on. I remember having a conversation with a cousin, who mentioned that her own daadi was buried in Calcutta, but because of the difficulties created after Partition, subsequent generations cannot visit the burial site. Despite more than 70 years having passed since her daadi’s death, the feeling of loss is one she continues to feel to date.

Historians claim that the 1947 Partition was history’s greatest and bloodiest mass migration of people. As I write this, the United Nations (UN) resolution against the US recognising Jerusalem as the capital of Israel is still very fresh. Aung San Suu Kyi is facing backlash over Myanmar's treatment of the Rohingyas, the ongoing war in Syria has a continually devastating humanitarian effect, and Yemen faces triple threat in the form of conflict, famine and cholera. What makes these crises different from the 1947 movement is perhaps the purpose being served in each event. In the largest crises all over the world, be it Kashmir, Palestine, or the Rohingyas, people are being denied access to their homeland. However, during 1947, refugees were moving to their newly created homeland – the ultimate aim of creating Pakistan.

While each refugee movement might be different, however, the one binding point is the involvement of people at large, which makes the rehabilitation of people a difficult feat. With each of these crises in mind, Home 1947 would resonate with even the hardest of hearts, because SOC successfully enables us to relive the Partition through the stories and struggles shared by our own people. Only by fully understanding the “people” element of 1947 can we comprehend that forcibly leaving one’s home most definitely changes a person forever.

All photos: Sarah Fazli

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ