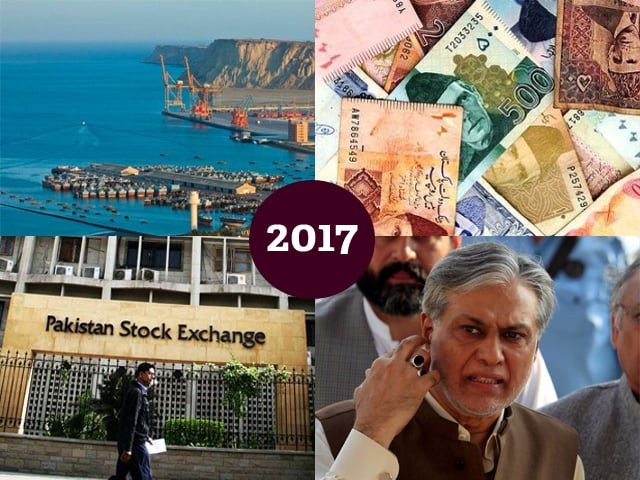

There were a lot of fairly good economic indicators seen in 2017, such as the following:

- An 8.5% growth in Large-Scale Manufacturing (LSM),

- An inflation rate of 3.9%,

- A super-strong growth in lending to the private sector,

- A 74.4% growth in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) worth $939.7 million,

- A 19.5% growth in the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) Tax Revenues and a double-digit growth in exports

Amidst these “good” indicators, less focus was paid to the depleting foreign currency reserves and burgeoning imports.

Whether this is due to Mr Ishaq Dar being pre-occupied during the year, trying to save himself and his boss from the aftermath of the Panama leaks, or merely because the anticipated growth of imports was foreseen in a naïve manner, is a question that is behind us for now. With the grip on currency loosening, the picture alas seems to slowly be moving towards equilibrium. When the currency started slipping in December, there was no “inquiry” conducted by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), as was the case earlier in July when the government ordered SBP to look into the matter. In contrast, SBP released a statement in December saying,

“The SBP is of the view that this market-driven adjustment in the exchange rate will contain the imbalance in the external account and sustain the higher growth trajectory.”

If the SBP had released this statement in July, it would have surely avoided us a lot of negative publicity, both domestically and abroad, over the “economic fragility” of the country. Many economists, distinguished writers and federal office holders have penned down a “doomsday” scenario, while optimists, including myself, advocate this very same “fragility” as a solvable matter, and try to instil hope while pleading for better policies.

While economic data fudging, such as selling Pakistan Security Printing and liquefied natural gas (LNG) plants to other government departments, with the aim to window-dress the fiscal deficit, is not appreciated, yet it is part and parcel of a developing nation of our scale. What is not permissible, however, is negligence and taking the economic responsibility of 198 million people for granted, just because you have grass-root political streams that ensure your vote bank on the basis of baradari (status), language, ethnicity, tribal allegiance as well as emotional sympathies, derived either for leaders that are assassinated, or for leaders who are ousted by military dictators.

To illustrate, in the first quarter of the Fiscal Year 2018, over $2 billion were spent on debt-servicing and defence spending also increased, respectively. We live as a nuclear-armed Muslim nation in a hostile region, where the definition of terrorism has blurred over the past decades to suit the interests of those in power. Given our expenditures, be it our need to fence our Afghan border at a cost of $532 million, move the General Headquarters (GHQ) to Islamabad at a cost of Rs100 billion, launch a 600-tonne maritime patrol vessel (MPV) or get more JF-17 Thunders, we need more tax revenues.

The chief of army staff has also acknowledged the state of the economy, with a strategy being devised to bring more than the 125,000 armed forces personnel who are currently under the tax net. A similar move from our honourable chief justice or our prime minister, in the form of a memo to all government departments, would bring a tectonic shift in the wave against corruption and a rise of the nation.

Countries thrive when it seems obvious that the leaders – whether elected or otherwise – work with sincerity to achieve prominence in the global arena. We live in the 21st century where we compete with the likes of fast-growing, knowledge-based economies, such as those of India, China and South Korea. Innovation (entrepreneurship), coordination (redistribution of wealth between regions), greening (cleaner environment bolstering the quality of life), opening up (geopolitics forging alliances) and inclusiveness (the fruits of development with the under-developed) are five basic ingredients which we did not need to wait to copy from China’s five-year plan.

One step in the right direction would be to give greater priority to harnessing the trust of the masses over the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). The government taking loans and making investments (the investments are a quasi-loan because of guaranteed returns) is acceptable as long as the net value is positive. What we need to encourage the Chinese to do is a transfer of technology and to undertake a joint venture with their Pakistani counterparts. Concessions, in the form of tax and otherwise, should be given to local players in the Special Economic Zones being set up, whereas job creation should be incentivised with tax benefits.

Political relationships also have underlying vested interests behind them. What Pakistan should do is to not just buy the security alliance of the next super power in wake of the US and India, but also learn from their economic expertise, especially as China moves towards being a more innovation-based country.

Economically, 2017 was marred with rising Current Account Deficit (CAD), standing at $5 billion in the current fiscal year – an exponential rise compared to $3.59 billion last year. Plugging the gaping hole with an additional borrowing of $3 billion from Eurobonds and Sukuk buys us breathing space, but is not the solution. The government can and will do more harm if it starts arresting the necessary rise in imports by making them more expensive through duties. At over 15 % of our gross domestic product (GDP), imports are definitely not tilted towards luxury goods for a country with a paltry GDP per capita of $1,443.

Alarmingly, our exports as a ratio of GDP reached an all-time low, and are a problem worth addressing for good. Anyone advocating a rapid 15% depreciation is perhaps overlooking the impact of that decision on:

- Rising fuel prices (RLNG is linked to oil prices),

- Potential increase in debt servicing if interest rates increase,

- Contraction in the consumption led economic growth.

If the exporters justifiably demand a level-playing field, they should be given a cost of fuel similar to that of their competitors. If the currency is let loose, translating into a creeping inflation and a 2% increase in discount rate, the additional annual interest cost burden on the exchequer would be Rs600 billion ($5.75 billion), which would put pressure on the Public Sector Development Programme (PSDP) and other fiscal development programs.

If, on the other hand, the government drastically reduces the energy tariff for exporters to $6/MMBtu, the cost of such would be less than Rs90 billion ($850 million) per year, but could incrementally lead to $6-8 billion of additional dollar inflows, leading to a 2-2.7% reduction in the current account deficit. This could completely address fears of depreciation, and generate further economic activity at the cost of $850 million at 0.2% of GDP. If it doesn’t, the very dollars are then “borrowed” internationally, and the financial cost of this would nonetheless be $300-$450 million approximately.

Yes, the country is going to be load-shedding free. Yes, CPEC projects will give us the infrastructure to get our act together. The relevance of electricity in the knowledge-led economic growth is trivial yet important, just like having internet in your office so you can add value and develop IT software, performing your role in the service industry. The office-bearers must pay heed to the fact that in order to garner respect in the world, we need to grow economically. With 63% of our population comprising of youth, and 69 million aged below 15, we need to create jobs and provide them with an education.

If 2018 is to be any better than previous years, we need to continue with an economic growth rate of above 5% for next 10 years, which would require putting social and economic development in the doctrine of “national interest”. Foreign entrants, such as Hyundai, Kia, Renault, Puma Energy, Alibaba and Uber have, through their entry, acknowledged the economic potential of a nation with a young population. What is required from the policy makers is a vision to lead forward, similar to China’s five-year political, social and economic plans. And this, invariably, requires continuity in the policies and keeping the interest of the nation – the infamous “national interest” – above political and personal interests.

Here’s hoping for a better 2018!

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ