By a majority of three to two (Asif Saeed Khan Khosa and Gulzar Ahmed) dissenting, the honourable five-member bench ordered the Constitution of a joint investigation team (JIT) which would investigate into and find answers to 13 questions put forth by the honourable bench.

It was ordered that the JIT should complete its investigation and submit its final report within a period of 60 days from the date of its constitution. In consequence, the investigation into one of the most high profile cases in Pakistan’s history thus began.

The JIT submitted its final report before the three-member special bench on July 10, 2017. Before its constitution, during its working and after the submission of its report, several questions have been raised by jurists, media persons and politicians regarding different aspects relating to the case and JIT.

Some of the raised questions will be addressed and answered in this article. I am basing the answers on my humble jurisprudential understanding. The questions and my answers thereto are:

1. Who will pass the final order in the Panama Leaks case based on the JIT’s final report? Will a new, larger or full bench be constituted?

As the deadline for the submission of the final report drew closer, a debate began on our television channels as to whom or which bench has the jurisdiction to pass a final order in the Panama case. Several analysts and legal minds opined and addressed the question. Three opinions surfaced – (i) a new bench will be constituted, (ii) the original five-member bench would resume its proceedings since the three-member bench may stand dissolved with the submission of the JIT’s final report, and (iii) the three-member special bench would pass a final order.

Although the judgment/order passed on April 20th by the five-member bench may technically be referred to as interim in nature, the bench seems to have definitively culminated its own proceedings upon pronouncing it.

The power to pass a final order has been left with the three-member special bench, which is quite clear from a bare reading of paragraph three and four of the order of the Court, which states,

“3. The JIT shall submit its periodical reports every two weeks before a bench of this court constituted in this behalf. The JIT shall complete the investigation and submit its final report before the said bench within a period of 60 days from the date of its constitution. The bench thereupon may pass appropriate orders in exercise of its powers under Articles 184(3), 187(2) and 190 of the Constitution including an order for filing a reference against respondent number one and any other person having nexus with the crime if justified on the basis of the material thus brought on the record before it.

4. It is further held that upon receipt of the reports, periodic or final of the JIT, as the case may be, the matter of disqualification of respondent number one shall be considered. If found necessary for passing an appropriate order in this behalf, respondent number one or any other person may be summoned and examined.”

It is crystal clear that the five-member bench has not retained any powers or authority to pass the final order. In regards to the sending of a reference to the National Accountability Bureau (NAB), the power to pass an order in this regard has unequivocally been given to the three-member special bench.

Similarly, by implication, the power to pass an order of disqualification has also been given to the three-member bench since this power could be exercised either upon submission of the periodic or the final report, which were to be submitted to the special bench.

This settles the question of whether the five-member bench or special bench has the authority to pass a final order.

In regards to the constitution of a larger or full bench, it may be noted that administratively, the chief justice of the Supreme Court is empowered to constitute a larger or full bench for adjudication upon a matter.

This power, however, is usually exercised upon recommendations of the bench before which a case is already pending. Since the three-member special bench has absolutely and completely been empowered by the five-member bench to conclusively adjudicate upon the matter, it is unlikely that such a recommendation would be sent, even upon the application of a party to the case.

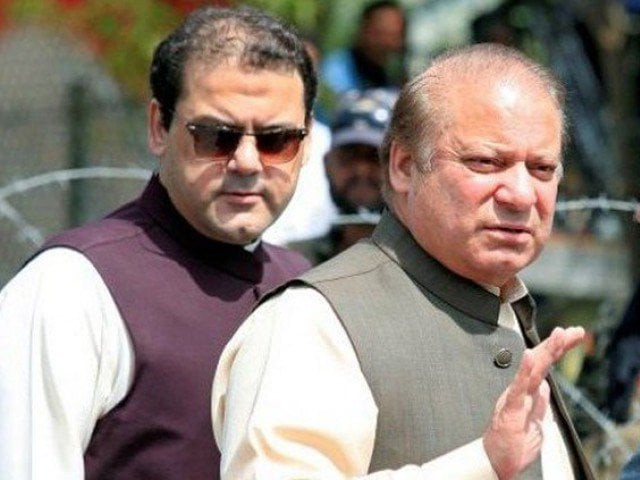

It is thus most probable, in my opinion, that the three-member special bench would pass a final order in this case. The order will decide whether Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif stands disqualified or not and if a reference against any of the respondents, or any other person, is to be sent to the NAB.

Further, the bench has also been empowered to pass any other ‘appropriate’ order in exercise of powers under Articles 184(3), 187(2) and 190 of the Constitution. Such orders may include orders of dismissal or suspension of the head of an institution to which a reference may be sent.

Thus, under Article 184(3) and 187(2), the bench may order the removal of the chairman NAB. The five-member bench had passed damning remarks on his partiality and incompetence, which have been substantiated in the JIT’s report.

2. Do the parties (respondents in this case) have the option of filing objections to the JIT’s report? Under what circumstances will such objections be entertained by the court?

This question is linked with another intricate question pertaining to the legal status of the JIT. Powers and status of the JIT are, in my opinion, governed by the order of the five-member bench. As opposed to a local commission or an investigation officer, the JIT is not a statutory entity. No specific powers or procedure for the JIT have been given under any law.

It has instead been formed by order of the Supreme Court exercising its powers under Article 184(3) of the Constitution. The JIT was formed by the Supreme Court for fetching answers to key questions raised by the court itself during proceedings on petitions. Its legal status can thus only be defined by the court. Procedure and mandate of the JIT, as given by order of the court, was inquisitorial and by no means adversarial. Only the respondents, their witnesses or witnesses called by the JIT, appeared before it. Neither the petitioners, nor any witnesses put forth by them were examined.

If proceedings of the JIT were to be given an adversarial tinge, it can only be done by proving that the JIT, or the court itself acted as an ‘adversary’ to the respondents. Attempts have been made and are still being made to establish this conjecture however fruitless they may be.

In my opinion, any objections filed by the respondents will have to stand on either of the two presumptions:

- That the JIT was undoubtedly biased or partial against the respondents, and

- That the JIT blatantly violated their mandate, principles of justice and legal provisions. At the moment, none of this seems even close to being established, not from what has been said before the media at least.

For instance, if the respondents were to prove that the JIT misquoted them or their witnesses in the report, it will need to be proved, or at the very least, a reasonable doubt will need to be created. Unless these allegations are true, it will be impossible to caste a doubt especially in the presence of video and audio recordings.

If it is alleged that the allegation of forgery and falsification is baseless, the allegers will need to prove Calibri’s availability before 2007, and thus disprove Microsoft’s claim otherwise.

Thus, even though parties do have a right to file objections to the JIT’s working and report, it seems highly unlikely that the objections – unless exceptionally sound, cogent and well founded – will be entertained.

The allegations of bias levelled against the JIT will need to be established through evidence. Burden of proof will be on the allegers and not the JIT. As yet, no evidence has been brought forward or shown to the public, nor has it been claimed that there is any evidence kept for Supreme Court’s eyes only.

Objections pertaining to members of the JIT have already been dismissed by the Supreme Court, and thus establishing that any one of the members was working on a hidden agenda may not be easy in the absence of strong, cogent evidence.

3. Did the JIT go beyond its mandate?

To address this question, one first needs to understand the mandate given to JIT by the five-member bench. It must be kept in mind that the bench did not restrict itself to the prayers contained in petitions.

Instead the bench, on its own, devised 13 key questions considered relevant and significant to conclusively and comprehensively adjudicate upon the matter before it. The mandate of the JIT was thus not governed by what was prayed for by the petitioners, but by what was asked by the court.

In that, the JIT doesn’t seem to have crossed any lines. The Supreme Court empowered the JIT to investigate into and answer the following main questions:

- How did Gulf Steel Millcome into being?

- What led to its sale?

- What happened to its liabilities?

- Where did its sale proceeds end up?

- How did they reach Jeddah, Qatar and the UK?

- Whether respondent’s number seven and eight in view of their tender ages had the means in the early 90s to possess and purchase the flats?

- Whether sudden appearance of the lettersof Hamad Bin Jassim Bin Jaber al Thani is a myth or a reality?

- How bearer shares crystallised into the flats?

- Who in fact is the real and beneficial owner of Nielsen Enterprises Limited and Nescoll Limited?

- How did Hill Metal establishment come into existence?

- Where did the money for Flagship Investment Limited and other companies set up/taken over by respondent number eight come from?

- Where did the working capital for such companies come from?

- Where do the huge sums running into millions gifted by respondent number seven to respondent number one drop in from?

Additionally, two other queries were also put forth:

- The JIT shall investigate the case and collect evidence, if any, showing that respondent number one or any of his dependents or benamidars(fictious persons) owns, possesses or has acquired assets or any interest therein disproportionate to his known means of income.

- The JIT may also examine the evidence and material, if any, already available with the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA)and NAB relating to or having any nexus with the possession or acquisition of the aforesaid flats or any other assets or pecuniary resources and their origin.

As is evident, an all-encompassing mandate was given to the JIT. It can even be said that considering the enormity of its scope, it was almost impossible to go out of its ambit.

Furthermore, the bench said that this needs a “thorough” investigation which means thereby, that all matters even closely related to any of the above questions became relevant. No limits could be imposed with regard to how far back in time the JIT needed to go with its investigations or how it stretched its inquiry horizontally or vertically.

Again, to establish the allegation that the JIT went out of its mandate, it will need to be proven that any specific action or aspect of its inquiry was absolutely irrelevant to the 13 (+two) questions. Again, that is unlikely.

4. Can the bench pass a final order regarding respondent number one’s (PM’s) disqualification or will there be a trial first?

This question has recently been raised, even by certain glorified jurists and human rights activists. It has been said that the JIT report’s status is that of a ‘police challan’ and no final order can be passed without a proper trial. Thus, all that the bench can do is refer the matter to another forum for a proper trial.

Firstly, the judgment of the five-member bench was quite clear on assumption of the jurisdiction under Article 184 (3) over the case. The only disagreement, as I see it, was with regard to the mode of exercising that jurisdiction; whether to pass an order or a declaration directly, or to first have a thorough investigation first and then pass an order.

It is interesting to note that there was a tinge of the allegedly buried ‘doctrine of necessity’ in the judgment. Jurisdiction was acquired after holding (unanimously) that it is due to the failure of state institutions responsible for checking and eradicating the evils of corruption, money laundering etc., that the Supreme Court is left with no other option but to assume jurisdiction over this matter. The same reasoning has been given for forming a JIT instead of trusting NAB with the investigation.

It needs to be kept in mind that if the Supreme Court were to render itself powerless in the face of technicalities and obstacles, it may not have assumed jurisdiction in the first place. If the grounds for assuming jurisdiction were the consistent failure and ineffectiveness of the legal system and machinery in place, the same system and machinery will not be resorted to after spending more than a year in this exercise.

The Supreme Court has unfettered powers under Article 184(3) when it comes to matters of public importance. It has already assumed jurisdiction over this matter, deeming it a case of immense public importance and will see it through.

In my opinion, the court will decide upon the PM’s disqualification, be it for or against it, without any trial or further proceedings. The PM may be summoned for appearing on the next date of hearing, which may be July 24th, where his fate may be decided.

It will also be decided whether references shall be sent to NAB and who else should be arrayed as the accused in such a reference. Further, the fate of chairman NAB may also be decided before a reference is sent. As for allegations of falsification and forgery of documents against other respondents is concerned, the same will not be decided by the special bench and may instead be referred to a proper forum.

5. Did the JIT have outside help, from the ‘establishment’, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) in particular?

This is not a strictly legal question. However, I would like to comment on it as follows. This question has been raised by several persons within and without the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N).

Even though professionals in the JIT were competent enough to investigate the matter and write a comprehensive report within 60 days, ready availability of certain documents and foreign assistance to it has raised a few eyebrows. I, for one, do believe that the JIT was helped by the ISI.

But was it an ‘outside’ help?

One member each from the ISI and Military Intelligence (MI) were inducted in the JIT upon the Supreme Court’s directions. Reasons for doing so may vary from their institutional professionalism to resourcefulness, but the fact remains that they were officially a part of the JIT and thus all their resources were readily available to the JIT in the performance of its functions.

So these are two different questions erroneously asked in conjunction. Yes, the JIT was aided and helped by the ISI. No, that does not mean it had any ‘outside’ help. The five-member bench also directed all state institutions and the respondents to cooperate with and facilitate the JIT in the performance of its task. Thus, even if it weren’t a member of the JIT, ISI was duty bound to assist it.

The post originally appeared here.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ