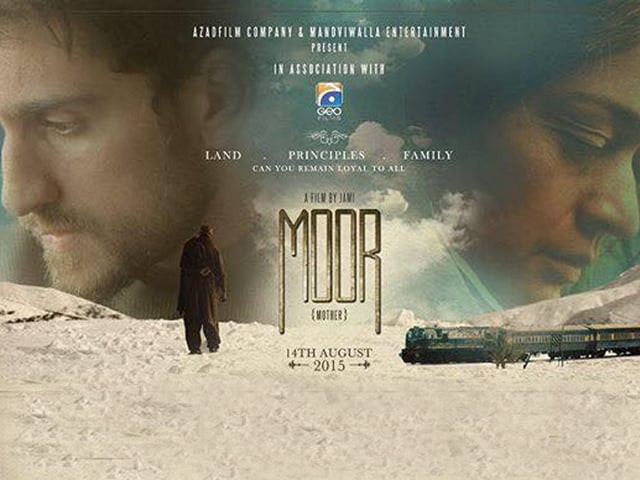

Afghanistan remains to be the centre of attention with a complicated set of woes and a new administration in place, and China is slowly becoming one of the biggest film markets in the world. In the middle of this hue and cry lies Pakistan and its cinema industry’s struggle to evolve into something better than Lollywood. That’s where Moor comes in.

Here are six reasons to embrace Moor and why it sets the bar high for future Pakistani productions:

1. A genuine Pakistani film

Photo: Moor official Facebook page

Photo: Moor official Facebook pageThough there is nothing wrong with carrying on the song-dance-romance formula of Lollywood and with that more people will be attracted towards cinemas, but then your identity will not be anything more than an extension of Bollywood, a prime example of this is Na Maloom Afraad.

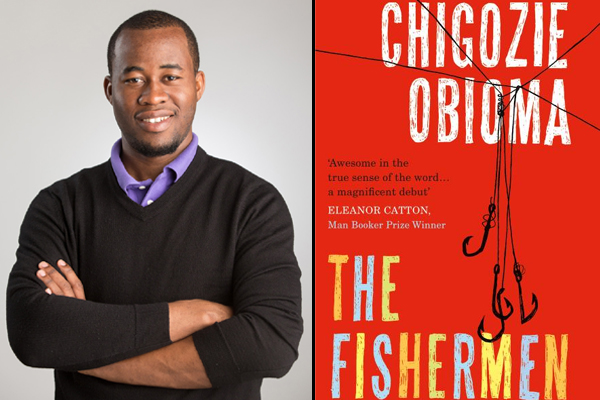

On the opposite side of Na Maloom Afraad and Nabeel Qureshi are Jami Mahmood and his outstanding film, Moor. Without relying on any conventions or ‘formula’, he offers a story that is truly a product of our times and geography, without compromising on cinematic experience.

2. Possibly the last film on Balochistan

Photo: Moor official Facebook page

Photo: Moor official Facebook pageI don’t actually know whether Balochistan has previously been featured on the big screen or not, but one thing’s for sure, it will not happen again. Moor is possibly your only window into the highlands of Balochistan and the only major portrayal of its people’s loyalty towards their soil and principles.

Celebrated Pakistani photographer Kohi Marri once said,

“Such is the beauty of the landscape of Balochistan that we can shoot an entire Lord of the Rings here.”

The visual magnum opus that Moor has turned out to be is more or less, the culmination of Marri’s account. The only difference is that Frodo Baggins was aided by the fellowship and Wahidullah Khan (Hameed Sheikh) only has a fragile family by his side.

Stylistically speaking, there are plenty of beauty shots in the film — offering the Pakhtun belt of Balochistan as a possible tourist spot for the rest of the world.

Photo: Moor official Facebook page

Photo: Moor official Facebook pageIt’s ironic that the only film to come out in recent years that highlights the concept of ‘motherland’ in all honesty, without using propaganda, has come out of Balochistan, a province that is fighting too many wars at one time. Jami and the clan actually took permissions from the members of Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), who had taken over the Muslim Bagh railway station, to shoot the film. And Muslim Bagh is a part of the much “peaceful” and less barren Pakhtun belt of the province. The rest is self-explanatory.

3. Product of our times

The storyline is based on the closure of the Zhob Valley railways in 1984. The film shows how a family is affected by growing corruption in the system and how the influential have destroyed the entire railway network to support a road route through the province. Although it may not be as big an issue for a province like Balochistan, but the way the director generates pure human drama from elements alien to the urban audiences is simply outstanding. At times, it may seem that the film is taking place in an alien land, but it is in turn a product of our times and our actions.

4. Spectacular Performances

Sheikh’s journey from complete sanity to neurosis is not only reflected through his swift aging post-crises, but also the subtle brilliance with which his mannerisms become more timid with time.

Photo: Moor official Facebook page

Photo: Moor official Facebook pageShaz Khan adapts the Pakhtun accent fluently and effortlessly while maintaining his composure — almost comparable to a dead volcano; whenever he did erupt on screen, you knew from within your being that he means business. Abdul Qadir as Baggu Baba turns out to be the highlight of the film.

Photo: Moor official Facebook page

Photo: Moor official Facebook pageBaggu generally preserves a very goofy attitude towards things but doesn’t let the viewer confuse him for a clown. He, in many ways, represents the true essence of a native, one who would kill or get killed for his soil. The most exceptional part of Qadir’s portrayal of Baggu is that he actually serves as the moral compass of the story but never asserts it.

Even guest appearances by Ishtiaq Nabi, Nayyar Ejaz, and Sonya Hussain are well gauged and to the point.

5. A character building experience

It is an art to disseminate a moral standing through your medium and not sound preachy. This is perhaps the biggest achievement of Moor, because the central conflict of the film stands on purely moral grounds and evolves purely on moral choices, making it a naturally humbling experience. Such is the demeanour and mannerism of these characters of Khost, that they almost appear like the cinema equivalents of Red Indians in a Hollywood film and similarly for a few moments, they make us feel ashamed of our lives which revolve around smart phones and desires generated by advertising.

6. The spine-chilling music

As for the music, the soundtrack of the film when listened to in isolation seems something out of the Strings’ Coke Studio but provides a spine-chilling experience when teamed with snow-capped mountains. ‘Gul Bashri’ by Rahim Shah in particular hits you like a cold breeze cuts through your muffler on a dark winter night — it’s haunting but hopeful.

Rating: Four out of five

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ