60 years ago Saadat Hasan Manto knew what Pakistan was in for today

Manto envisaged a future where music, art and even Iqbal's poetry is censored to create, literally, a ‘Pak-istan’.

“I have seen him;

On the cleanest roads, in a dust-covered amazement;

In the gathering storm of blind, overturned cups;

Tossing the empty bottle he shouts,

‘Oh world! Your beauty is your ugliness.’

Booms becoming the noise of chains,

The world stares back at him,

Their bloodshot eyes rattle with the question,

‘Who nabs the pillar of time,

By the noose of his drunken breath?

Who dares to break into dim corridors,

Of twisted conscience?

Who intrudes upon poisonous dens,

Of demonised souls?

Through icy glasses his rude glance,

Chases us like a footfall,

Foul monster!

Bang! Bang!”

(A poem for Manto - Majeed Amjad)

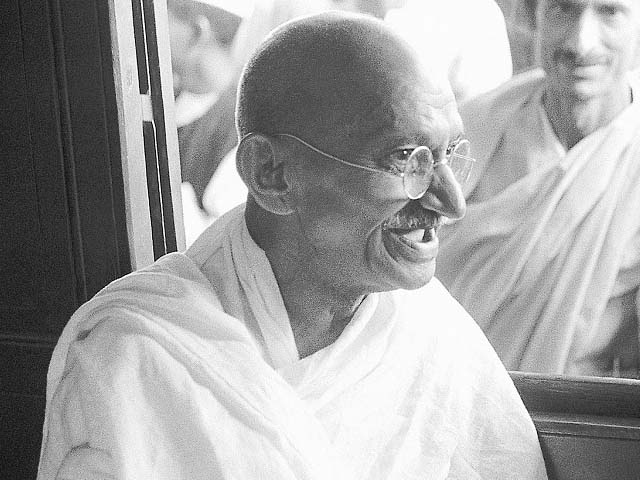

The man who saw beauty in the world’s ugliness and for whom this poem was written shortly before his untimely death was none other than Saadat Hasan Manto, the rebel and one of Pakistan’s greatest writers and social critics. Manto died 60 years ago today.

Manto’s own life mirrored the characters he portrayed in his famous short-stories, sketches and his powerful non-fiction. He was a writer with a deeply political vision, and this vision was reflected uncompromisingly in his work. It also reflected the contradictions of Pakistani society because he himself hated hypocrisy and refused to partake in them.

For example, he foresaw presciently many of the patterns our state and society forged with religion, India and the United States as early as the 1950s, with devastating wit and satire; take Manto’s ‘Letter to Uncle Sam’. These letters were written in the early 1950s, when the contours of Pakistan’s foreign policy were just beginning to be shaped by an unconstitutional government. Though written in a bitingly satirical vein, they contain a remarkable overview of the history, politics, culture and international relations of the period as it affected not only Pakistan and India, but the wider world as well. This could be witnessed from the prime minister’s tour of Washington two years ago, where an overgenerous aid package of $1.6 billion was rolled out while the prime minister’s plane was still in mid-flight. What Manto cautioned against was not just dependence on American kiss-proof lipstick – an appellation which Manto found disappointingly inaccurate – but also economic dependence, and its less savoury aspects like American-armed jihadis in Manto’s time, and Saudi and Canadian ones in our own.

In his fourth letter ‘posted’ in 1954, he wrote,

“India may grovel before you a million times but you will definitely make a military aid pact with Pakistan because you are really worried about the integrity of this largest Islamic sultanate of the world and why not, as our mullahs are the best antidote to Russia’s communism. If the military aid starts flowing, you should begin by arming the mullahs and dispatch vintage American (dry cleaning) stones, vintage American rosaries and vintage American prayer mats, with special attention to razors and scissors, and if you bless them with the miraculous prescription of vintage American hair dye as well then do understand that the cat is in the bag. The purpose of military aid as far as I understand it is to arm these mullahs, I’m your Pakistani nephew but I am aware of all your machinations but this heightened intelligence is all thanks to your politics (God save it from the evil eye). If this sect of mullahs is armed American-style, then the Soviet Union will have to pick up its spittoon from here, even whose gargles are mixed up in communism and socialism.”

Satire apart, Manto was probably the first observer who foresaw early America’s disastrous foreign policy in various parts of the Muslim world in the 1950s and 1960s leading right up to the war against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan, of assisting Islamic fundamentalist parties against the threat of rising communist and secular-nationalist forces, a process which has now come full-circle with the unannounced execution of one of their own armed mullahs Osama bin Laden, in Abbottabad. He thus accurately foretold the contradiction in the poisonous US-Pakistan relationship and one only need look at the headlines screaming at us from the newspapers today to confirm this.

In Save India from Its Leaders, here is an evocative passage which serves to highlight his foresight in predicting the rise of such opportunists and time-servers as newly-elected Narendra Modi and re-elected Nawaz Sharif, Anna Hazare, Asif Zardari, Tahirul Qadri and even the mercurial Imran Khan:

“These people who are commonly known as leaders, view politics and religion as that crippled, lame and injured man, displaying whom our beggars normally beg for money. These so-called leaders go about carrying the carcasses of politics and religion on their shoulders and to simple-minded people who are in the habit of accepting every word uttered to them in high-sounding vocabulary, they bandy about that they will breathe new life into this carcass. Religion is the same as it has always been and will always remain so. The religious spirit is a concrete reality which can never change. Religion is a rock which cannot be affected by even powerful waves of the sea. When these leaders cry their hearts out telling people that religion is in danger there’s no reality to it. Religion is not something which can be endangered. If there is a danger, it is to these leaders who endanger religion to achieve their own ends.”

Significantly, Manto wrote this powerful indictment in 1942 in pre-partition India.

In Manto’s arguably most prescient essay, By the Grace of Allah, he envisages a future where everything, from music and art to literature, newspapers and even the poetry of the country’s national poet, poor Allama Iqbal, would be censored and banned, to create, literally, a ‘Pakistan’ (the land of the pure):

“Sirs, I forgot to mention science. It was literature’s maternal aunt. May Allah save us from this calamity, God forbid. They were concerned with making this finite world into paradise, these people who called themselves scientists. Accursed people, they used to claim the act of creation in competition with Allah, that we will create an artificial sun which will illuminate the whole world at night. Whenever we want, we would extract rain from the clouds. Consider, Nimrod was God, what else? Attempts were made to find a cure for an untreatable and dangerous disease like cancer, albeit throwing the gauntlet to Gabriel. One sahib holding binoculars, and claiming that he will reach the moon, another producing children in bottles and containers. They had lost all fear of God, these lowlifes. By the grace of Allah, all these devils have been raised from us.”

Now, 50 years later, we would have no problem recognising the malaise Manto so ably diagnosed then, as United Nations teams administering polio drops to beleaguered infants in the country’s north-western areas are attacked and murdered in cold blood by militants emboldened by fatwas outlawing vaccination. A section of clerics declared voting in the May 2013 elections un-Islamic!

Literature may not change societies, as it’s often sentimentally believed, but it can show the mirror to the latter by speaking truth to power. It stops being a mirror for societies when censorship intervenes and is used by the powerful to stifle dissenting alternatives. Manto’s life and work mirrored the contradictions of Pakistani state and society in the 1950s and the ruling elite used its courts and critics to silence him, but they could not silence his readers or the contradictions which today seem sharper than when Manto wrote and lived.

I became interested in translating Manto after noting with disgust and alarm that he had been exclusively pigeonholed as a realist of sex and partition, and at best as a great writer without an agenda, not as a social critic with a prescient vision. This trend continued in his birth centenary year in 2012.

Approaching his works from a social scientist’s angle undoubtedly helped, as did not having a formal training as a ‘literary critic’. Literary critics certainly had their share in Manto’s tortured existence in his final years and premature death. And I thought translating Manto’s non-fiction would set the mirror right and put Manto into proper context since it is in his essays that he reflects the future of Pakistan. In this sense, translation can sometimes act as a mirror to reflect the real man in ways a bird’s eye view cannot.

Secondly, Manto attracted me because his life, work and personality as a rebel unconsciously put me in touch with myself. It was first during my teenage years wrestling with issues of sexuality and teen angst while refusing to break any boundaries unlike my peers, who were more adventurous. Later, I became more mature and self-conscious, as a rebel who, while not really sharing Manto’s class background, circumstances or experiences in any way, rebelled from my middle-class origins and milieu in my college years, as a political activist shaped by Marxism not unlike Manto in his early years, as well as Pakistan’s special circumstances, firmly on the side of the poor and oppressed, in a secular and anti-imperialist narrative like Manto, in a society which still does not accept rebels and mavericks.

In dangerous times such as the one we are living in at the moment, even an act seemingly trivial as publicly reading extracts from Manto’s Letters to Uncle Sam in a packed auditorium during a conference at one of Pakistan’s most obscurantist universities becomes an insurgent act as does translating such intransigence into one of the world’s great imperialist languages. I also surmised that it might take a rebel to interpret another (more illustrious) rebel, which hasn’t been the case with Manto’s various other translators and interpreters so far. The final act of Manto’s rebellion resulted in a rather creative form of suicide – drinking himself to death at the age of 42 and writing his own epitaph in 1954, just a year before he died:

“Here lies buried Saadat Hasan Manto, with all the secrets of the art of short story-telling buried in his chest. He is still thinking, buried under tons of earth who is the greater short story-writer: he or God?” I’m mercifully still seven years short of that mark, and my rebellion is fortunately still going on…”

Speaking of rebels and rebellion, it would be apt perhaps to conclude with the last word from Manto himself:

“How could I bare a culture, civilisation and society that is already naked. I don’t even try to clothe it, because that’s not my job, but of the tailors. People call me black-penned but I don’t write on the blackboard with black chalk; I use white chalk so that the blackness of the board becomes even more evident…”

It is this extraordinary foresight, rebellion and rude glance at the future that make Saadat Hasan Manto a mirror for man, 60 years on.

COMMENTS (8)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ